Category Archives: German Romanticism

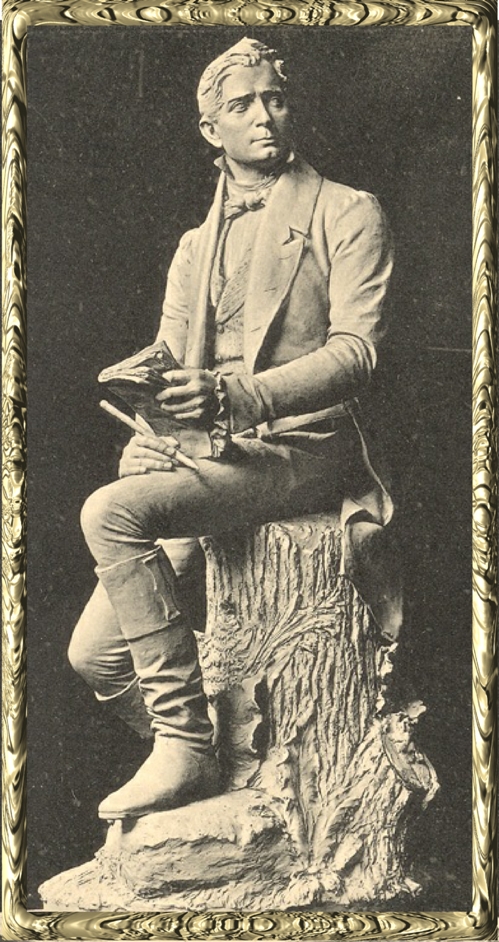

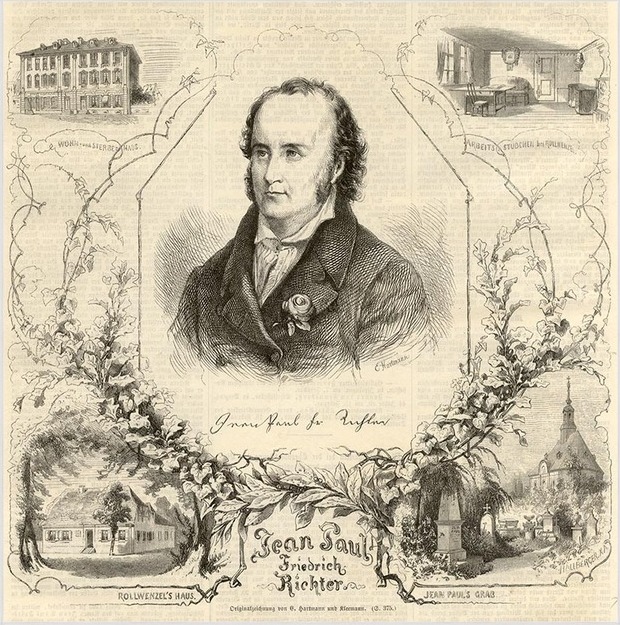

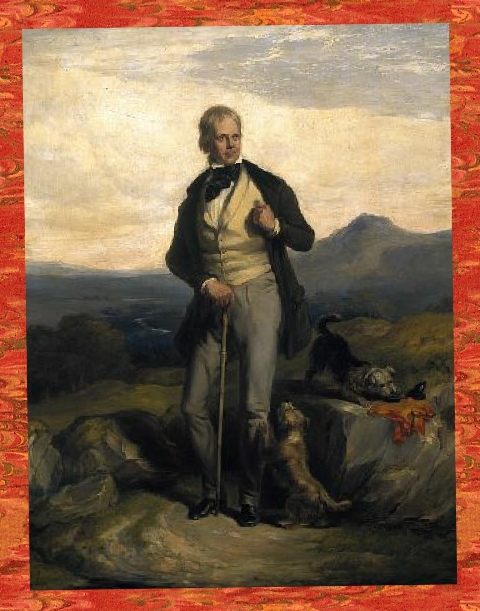

Thomas Carlyle: On Jean Paul

Excerpt: “Critical and Miscellaneous Essays: “Jean Paul Friedrich Richter” by Thomas Carlyle, 1827.

O then arose his inner Coliseum

Full of silent godlike forms of spiritual antiques,

And the torch-gleam of Fancy

Glanced round upon them like the

Play of a Magic Life

And there he saw among the gods

A friend

And a loved one … reposing.

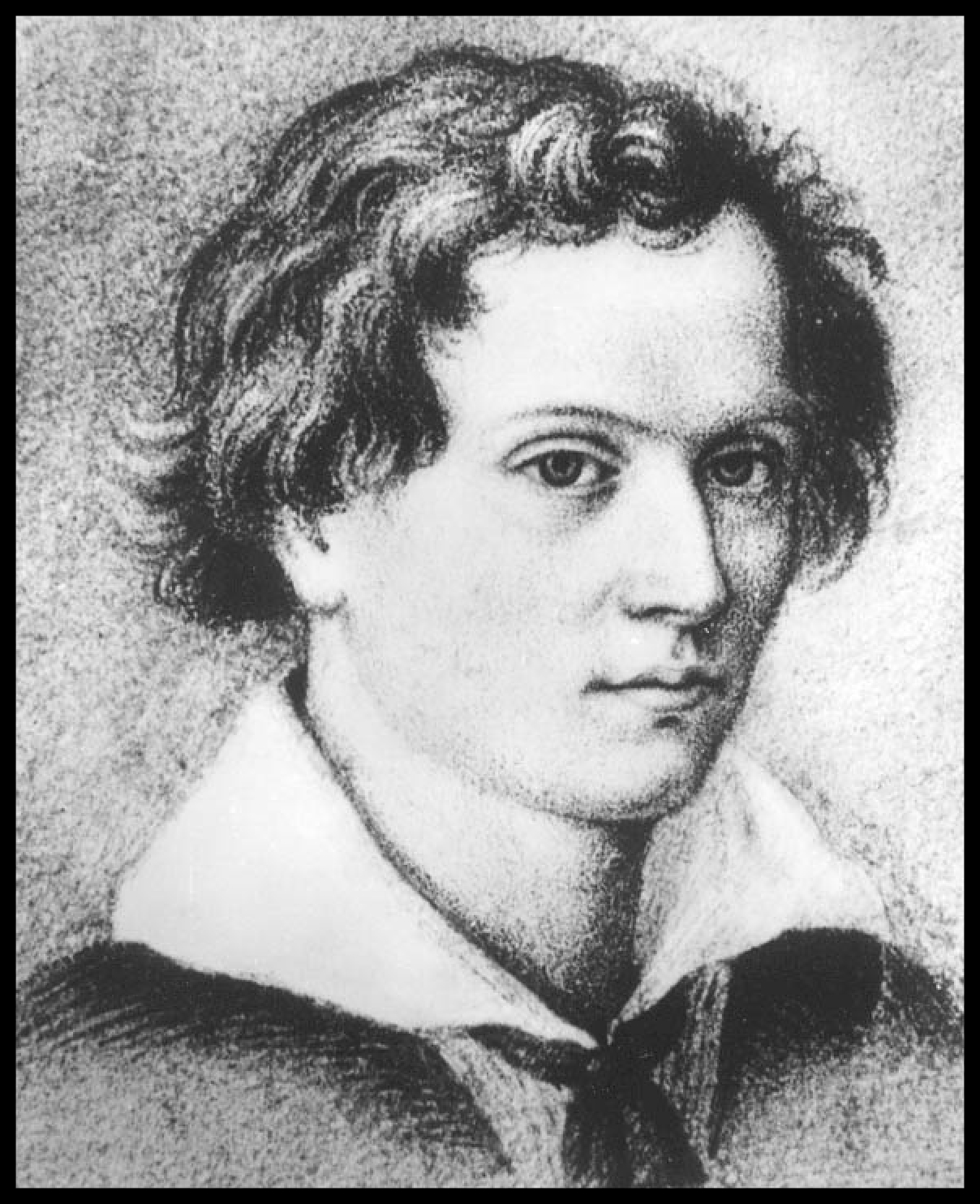

John Paul’s “Titan”

Except by name, Jean Paul Friedrich Richter is little known outside of Germany. The only thing connected with him, we think, that has reached this country, is his saying, imported by Madame de Staël, and, thankfully pocketed by most newspaper critics: “Providence has given to the French the empire of the land, to the English that of the sea, to the Germans that of — the air.” Of this last element, indeed, his own genius might easily seem to have been a denizen; so fantastic, many-colored. far-grasping, every way perplexed and extraordinary to his mode of writing.

To translate him properly is next to impossible; nay, a dictionary of his works has actually been in part published for the use of German readers! These things have restricted his sphere of action, and may long restrict it, to his own country; but there, in return, he is a favorite of the first class; studied through all his intricacies with trustful admiration, and a love which tolerates much. During the last forty years, he has been continually before the public, in various capacities, and growing generally in esteem with all ranks of critics; till, at length his gainsayers have either been silenced or convinced; and Jean Paul, at first reckoned half-mad, has long ago vindicated his singularities to nearly universal satisfaction, and now combines popularity with depth of endowment, in perhaps a greater degree than any other writer; being second in the latter point to scarcely more than one of his contemporaries, and in the former second to none.

The biography of such a distinguished person could scarcely fail to be interesting, especially his autobiography; which, accordingly we wait for, and may in time submit to our readers, if it seems worthy. Meanwhile, the history of his life, so far as outward events characterize it, may be stated in a few words. He was born in Wunsiedel in Bayreuth in March 1763. His father was a subaltern teacher in the Gymnasium of the place, and was afterwards promoted to clergyman at Schwarzbach on the Saale. Richter’s early education was of the scantiest sort; but his fine faculties and unwearied diligence supplied every defect.

Unable to purchase books, he borrowed what he could come at, and transcribed from them, often a great part of their contents – a habit of excerpting which continued with him throughout life, and influenced, in more ways than one, his mode of writing and study. To the last, he was an insatiable and universal reader, so that his excerpts accumulated and “filled whole chests.” In 1780, he went to the University of Leipsic; with the highest character, in spite of the impediments which he had struggled with, for talents and acquirement. Like his father, he was destined for Theology; from which, however, his vagrant genius soon diverged into Poetry and Philosophy, to the neglect, and, ere long, to the final abandonment of his appointed profession.

Not well knowing what to do, he accepted a tutorship in some family of rank; then he had pupils in his own house — which, however, like his way of life, he often changed; for by this time he had become an author, and, in his wanderings over Germany, was putting forth, now here, now there, the strangest books, with the strangest titles. For instance, “Greenland Lawsuits” – “Biographical Recreations under the Cranium of a Giantess” – “Selections from the Papers of a Devil” – and the like! In these describable performances, the splendid faculties of the writer, luxuriating as they seem in utter riot, could not be disputed; nor, with all its extravagance, the fundamental strength, honesty and tenderness of his nature. Genius will reconcile men to much.

By degrees, Jean Paul began to be considered not a strange cracked-brained mixture of enthusiast and buffoon, but a man of infinite humor, sensibility, force and penetration. His writings procured him friends and fame; and at length a wife and a settled provision. With Caroline Mayer, his good spouse, and a pension in 1802 from the King of Bavaria, he settled in Bayreuth, the capitol of his native province; where he lived therefore, diligent and celebrated in many new departments of Literature; and died on the 14th of November, 1825, loved as well as admired by all his countrymen, and most of those who had known him most intimately.

A huge, irregular man, both in body and in person, full of fire, strength and impetuosity, Richter seems, at the same time, to have been, in the highest degree, mild, simple-hearted, humane. He was fond of conversation, and might well shine in it. He talked as he wrote, in a style of his own, full of wild strength and charms, to which his Bayreuth accent often gave additional effect. Yet he loved retirement, the country and all natural things; from his youth upwards, he himself tells us, he may almost be said to have lived in the open air; it was among groves and meadows that he studied — often that he wrote. Even in the streets of Bayreuth, he was seldom seen without a flower on his breast.

A man of quiet tastes, and warm compassionate affections! His friends he must have loved as few do. Of his poor and humble mother he often speaks by allusion, and never without reference and overflowing affection. Wrote Doring, “Richter’s studying or sitting apartment offered about this time (1793) a true and beautiful emblem of his simple and noble way of thought, which comprehended at once the high and low. Whilst his mother, who then lived with him, busily pursued her household work, occupying herself about stove and dresser, Jean Paul was sitting in the corner of the same room, at a simple writing desk, with few or no books about him, but merely one or two drawers containing excerpts and manuscripts.”

Richter came later to live in finer mansions, and had the great and learned for associates; but the gentle feelings of those days abode with him: Through life, he was the same substantial, determinate yet meek and tolerating man. It is seldom that so much rugged energy can be so blandly attempted; that so much vehemence and so much softness would go together.

The expected Edition of Richter’s Works is to be sixty volumes; and they are no less multifarious than extensive; embracing subjects of all sorts, from the highest problems of Transcendental Philosophy, and the most passionate poetical delineations, to Golden-Rules for the Weather Prophet, and instructions in the Art of Falling Asleep. His chief productions are Novels: the Unsichtbare Loge (Invisible Lodge); Flegeljahre (Wild-Oats); Life of Fixlein; the Jubelsenior (Parson in Jubilee); Schmelzle’s Journey to Flatz; Katzenberg’s Journey to the Bath; Life of Fibel; and many lighter pieces; and two works of a higher order: Hesperus and Titan, the largest and best of his Novels.

It was the former that first (in 1795) introduced him into decisive and universal estimation with his countrymen; the latter he himself, with the most judicious of his critics, regarded as his masterpiece. But the name Novelist, as we in England must understand it, would ill describe so vast and discursive a genius; for, with all his grotesque, tumultuous pleasantry, Richter is a man of a truly earnest, nay high and solemn character, and seldom writes without a meaning beyond the sphere of common romancers. Hesperus and Titan themselves, though in form nothing more than “novels of real life,” as the Minerva Press would say, have solid metal enough in them to furnish whole circulating libraries, were it beaten into the usual filigree; and much which, attenuate it as we might, no quarterly subscriber could well carry with him.

Amusement is often, in part almost always, a mean with Richter; rarely or never his highest end. His thoughts, his feelings, the creations of his spirit, walk before us embodied under wondrous shapes, in motley and ever-fluctuating groups. But his essential character, however he disguise it, is that of a Philosopher and a moral Poet, whose study has been human nature, whose delight and best endeavor are with all that are beautiful, and tender, and mysteriously sublime … in the fate or history of man.

This is the purport of his writings, whether their form be that of fiction or of truth; the spirit that pervades and ennobles his delineations of common life, his wild wayward dreams, allegories and shadowy imaginings, no less than his disquisitions of a nature directly scientific.

Thomas Carlyle

Madame de Staël: On German Literature – The Schlegels

Part 2 of 2

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation).

After having done justice to the uncommon talents of the two Schlegels, we will now examine in what that partiality consists of which they are accused, and from which it is certain all their writings are not exempt. They are evidently prepossessed in favour of the Middle Ages and the opinions that were then prevalent; chivalry without spot, unbounded faith, and unstudied poetry, appear to them inseparable; and they apply themselves to all that may enable them to direct their minds and understandings of others to the same preference. W. Schlegel expresses his admiration for the Middle Ages in several of his writings, and particularly in two stanzas of which I now will give a translation.

“In those distinguished ages, Europe was sole and undivided, and the soil of that universal country was fruitful in those generous thoughts which are calculated to serve as guides through life and in death. Knighthood converted combatants into brethren in arms: they fought in defense of the same faith; the same love inspired all hearts, and the poetry which sung that alliance expressed the same sentiment in different languages.

Alas! the noble energy of ancient times is lost; our age is the inventor of a narrow-minded wisdom, and what weak men have no ability to conceive is in their eyes only a chimera; surely nothing truly great can succeed if undertaken with a groveling heart. Our times, alas! no longer know either faith or love; how then can hope be expected to remain with them.”

Opinions, whose tendency is so strongly marked, must necessarily affect impartiality of judgment on works of art. Without doubt, as I have continually repeated during the whole course of this work, it is much to be desired that modern literature should be founded on our history and our religion; it does not however follow that the literary productions of the Middle Ages should be considered as absolutely good. The energetic simplicity, the pure and loyal character which is displayed in them interests us warmly; but in the other hand, the knowledge of antiquity and the progress of civilization have given us advantages which are not to be despised. The object is not to trace back the arts to remote times, but to unite as much as we can all the various qualities which have been developed in the human mind at different periods.

The Schlegels have been strongly accused of not doing justice to French literature. There are, however, no writers who have spoken with more enthusiasm of the genius of our troubadours, and of the French chivalry which was unequaled in Europe, when it united in the highest degree, spirit and loyalty, grace and frankness, courage, and gaiety, the most affecting simplicity with the most ingenuous candor. But the German critics affirm that those distinguished traits of the French character were effaced during the course of the reign of Louis XIV. Literature, they say, in ages which are called classical, loses in originality what it gains in correctness. They have attacked our poets, particularly in various ways, and with great strength of argument. The general spirit of those critics is the same with that of Rousseau in his letter against French music. They think they discover in many of our tragedies that kind of pompous affectation, of which Rousseau accuses Lully and Rameau, and they affirm that the same taste which give the preference to Coypel and Boucher in painting, and to the Chevalier Bernini in sculpture, forbids in poetry that rapturous ardour which alone renders it a divine enjoyment; in short, they are tempted to apply to our manner of conceiving and of loving the fine arts the verses so frequently quoted from Corneille:

“Othon a la princesse a fait un compliment.

Plus en homme d’esprit qu’en veritable amant.”

W. Schlegel pays homage, however, to most of our great authors; but what he chiefly endeavors to prove is, that from the middle of the 17th Century, a constrained and affected manner has prevailed throughout Europe , and that this prevalence has made us lose those bold flights of genius which animated both writers and artists in the revival of literature. In the pictures and bas reliefs where Louis X!V is sometimes represented as Jupiter, and sometimes as Hercules, he is naked, or clothed only with the skin of a lion, but always with a great wig on his head. The writers of the new school tell us that this great wig may be applied to the physiognomy of the fine arts in the 17th Century: An affected sort of politeness, derived from factitious greatness, is always to be discovered in them.

It is interesting to examine the subject in this point of view, in spite of the innumerable objections which may be opposed to it. It is, however, certain that these German critics have succeeded in the object aimed at; as, of all writers since Lessing, they have most essentially contributed to discredit the imitation of French literature in Germany. But, from the fear of adopting French taste, they have not sufficiently improved that of their own country, and have often rejected just and striking observations, merely because they had before been made by our writers.

They know not how to make a book in Germany, and scarcely ever adopt that methodical order which classes ideas in the mind of the reader. It is not, therefore, because the French are impatient, but because their judgment is just and accurate, that this defect is so tiresome to them. In German poetry, fictions are not delineated with those strong and precise outlines which ensure the effect, and the uncertainty of the imagination corresponds to the obscurity of the thought. In short, if taste be found wanting in those strange and vulgar pleasantries which constitute what is called comic in some of their works, it is not because they are natural, but because the affectation of energy is at least as ridiculous as that of gracefulness. “I am making myself lively,” said a German as he jumped out a window. When we attempt to make ourselves anything, we are nothing. We should have recourse to the good taste of the French to secure us from the excessive exaggeration of some German authors, as on the other hand we should apply to the solidity and depth of the Germans to guard us from the dogmatic frivolity of some individuals amongst the men of literature of France.

Different nations ought to serve as guides to each other, and all would do wrong to deprive themselves of the information they may mutually receive and impart. There is something very singular in the difference which subsists between nations: the climate, the aspect of nature, the language, the government, and above all the events in history which have in themselves powers more extraordinary than all the others united. All combine to produce those diversities; and no man, however superior he may be, can guess at that which is naturally developed in the mind of him who inhabits another soil and breathes another air. We should do well then, in all foreign countries, to welcome foreign thoughts and foreign sentiments; for hospitality of that sort makes the fortune of him who exercises it.

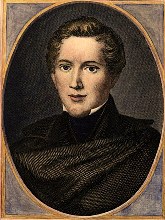

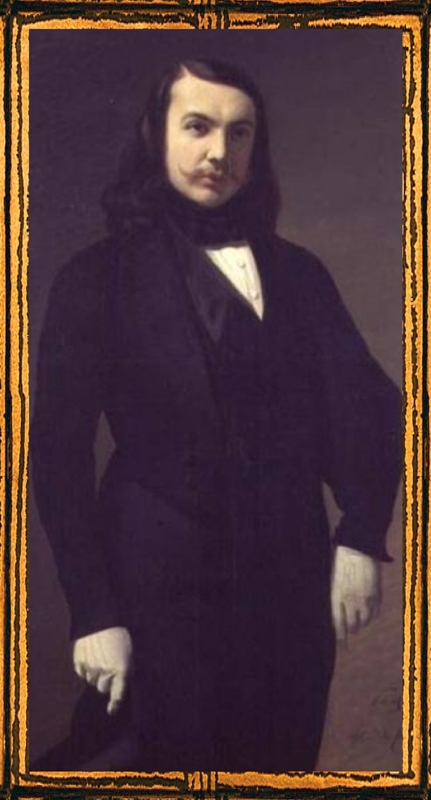

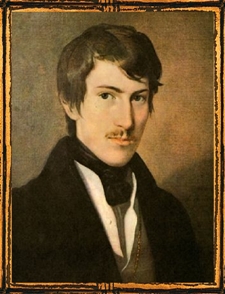

Friedrich von Schlegel

Madame de Staël: On German Literature – The Schlegels

Part 1 of 2

“When I began the study of German literature, it seemed as if I was entering on a new sphere, where the most striking light was thrown on all that I had before perceived in the most confused manner.”

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation).

For some time past, little has been read in France except memoirs and novels, and it is not wholly from frivolity, that we are become less capable of more serious reading, but because the events of the revolution have accustomed us to value nothing but the knowledge of men and things. We find in German books, even on the most abstract subjects, that kind of interest which confers their value upon good novels, and which is excited by the knowledge which they teach us of our own hearts. The peculiar character of German literature is to refer everything to an interior existence; and as that is the mystery of mysteries, it awakens an unbounded curiosity.

I will say a few words on what may be considered as the legislation of that empire; I mean criticism. There is no branch of German literature which has been carried to a greater extent, and as in some cities there are more physicians than patients, there are sometimes in Germany more critics than authors. But the analyses of Lessing, who was the creator of style in German prose, are made in such a manner that they may themselves be thought of as works.

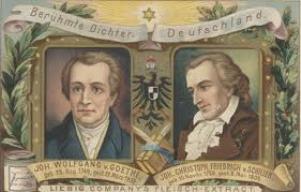

Kant, Goethe, J. de Mueller, the greatest German writers of every various kind, have inserted in periodicals of different publications recensions which contain the most profound philosophical theory and positive knowledge. Amongst the younger writers, Schiller and the two Schlegels have shown themselves superior…

The writings of A.W. Schlegel are less abstracted that those of Schiller; as his knowledge of literature is uncommon even in Germany, he is led continually to application by the pleasure which he finds in comparing different languages and different poems with each other; so general a point of view ought to be considered as infallible, if partiality did not sometimes impair it; but this partiality is not of an arbitrary kind, and I will point out both the progress and aim of it; nevertheless as there are subjects in which it is not perceived, it is of those I shall first speak.

W. Schlegel has given a course of dramatic literature in Vienna which comprises everything remarkable that has been composed for the theatre from the time of the Grecians to our days; it is not a barren nomenclature of the works of the various authors. He seizes the spirit of their different sorts of literature, with all the imagination of a poet; we are sensible that to produce such consequences extraordinary studies are required; but learning is not perceived in this work except by his perfect knowledge of the chefs d’oeuvre of composition. In a few pages we reap the labor of a whole life; every opinion formed by the author, every opinion, every epithet given to the writers of whom he speaks, is beautiful and just, concise and animated. W. Schlegel has found the art of treating the finest piece of poetry as so many wonders of nature, and of painting them in lively colors which do not injure the justness of the outline; for we cannot repeat too often that imagination, far from being an enemy to truth, brings it forward more than any other faculty of the mind, and all those who depend upon it as an excuse for indefinite terms or exaggerated expressions, are at least destitute of poetry as of good sense.

An analysis of the principles on which both tragedy and comedy are founded is treated in W. Schlegel’s course of dramatic literature with much depth of philosophy; this kind of merit is often found among the German writers. But Schlegel has no equal in the art of inspiring his own admiration; in general he shows himself attached to a simple taste, sometimes bordering on rusticity, but he deviates from his usual opinions in favor of the opinions of the inhabitants of the south. Their jeux de mots and their concetti are not the objects of his censure; he detests the affectation which owes its existence to the spirit of society, but that which is excited by the luxury of imagination pleases him in poetry as the profusion of colours and perfumes would do in nature. Schlegel, after having acquired a great reputation by his translation of Shakespeare, became equally enamored of Calderon, but with a very different sort of attachment that with which Shakespeare had inspired him; for while the English author is deep and gloomy in his knowledge of the human heart, the Spanish poet gives himself up with pleasure and delight to the beauty of life, to the sincerity of faith, and to all the brilliancy of those virtues which derive their coloring from the sunshine of the soul.

I was at Vienna when W. Schlegel gave his public course of lectures. I expected only good sense and instructions where the object was only to convey information; I was astonished to hear a critic as eloquent as an orator, and who, far from falling upon defects which are the eternal food of mean and little jealousy, sought only the means of reviving a creative genius.

Spanish literature is but little known, and it was the subject of one of the finest passages delivered during the setting at which I attended. W. Schlegel gave us a picture of the chivalrous nation, whose poets were all warriors, and whose warriors were poets. He mentioned that count Ercilla who composed his poem of the Araucana in a tent, as now on the shores of an ocean, now at the foot of the Cordilleras while he made war on those in revolt. Garcilasso, one of the descendants of the Incas, wrote poems on love on the ruins of Carthage, and perished at the siege of Tunis. Cervantes was dangerously wounded at the battle of Lepanto; Lope de Vega escaped by miracle at the defeat of the invincible armada; and Calderon served as an intrepid soldier in the wars of Flanders and Italy.

Religion and war were more frequently united amongst the Spaniards than in any other nation; it was they, who, by perpetual combats drove out the Moors from the bosom of their country, and who may be considered the vanguard of European christendom; they conquered their churches from the Arabians, an act of their worship was a trophy for their arms, and their triumphant religion, sometimes carried to fanaticism, was allied to the sentiment of honour, and gave to their character an impressive dignity. That gravity tinctured with imagination, even that gaiety that loses nothing of what is serious in the warmest affections, shows itself in Spanish literature, which is wholly composed of fictions and poetry, of which religion, love and warlike exploits are constantly the object. It might be said that when the New World was discovered, the treasures of another hemisphere contributed to enrich the imagination as much as the state; and that in the empire of poetry as well as in that of Charles V, the sun never ceased to enlighten the horizon.

All who heard W. Schlegel were much struck with this picture, and the German language, which he spoke with elegance, adding depth of thought and affecting expression to those high-sounding Spanish names, which can never be pronounced without presenting to our imaginations the orange trees of the kingdom of Grenada and the palaces of its Moorish sovereigns.

Wilhelm Schlegel, whom I here mention as the first literary critic of Germany, is the author of a French pamphlet lately published under the title of “Reflections of a Continental System.” This same W. Schlegel printed a few years ago at Paris a comparison the Phaedra of Euripides and that of Racine. It made a great deal of noise among the literary people of that place, but no one could deny that W. Schlegel, though a German, wrote French well enough to be fully competent to the task of criticizing Racine.

We may compare W. Schlegel’s manner of speaking poetry, to that of Winkelmann in describing statues; and it is only by such method of estimating talents, that it is honourable to be a critic: Every artist or professional man can point out inaccuracies which ought to be avoided. but the ability to discover genius and to admire it, is almost equal to the possession of genius itself.

Frederic Schlegel being much involved in philosophical pursuits, devoted himself less exclusively to literature than his brother; yet the piece he wrote on the intellectual culture of the Greeks and the Romans contains in small compass perceptions and conclusions of the first order. F. Schlegel has more originality of genius than almost any other celebrated man in Germany; but far from depending upon that originality, though it promised him much success, he endeavored to assist it by extensive study. It is a great proof of our respect for the human species when we dare not address it from the suggestions of our own minds without having first conscientiously examined into all that has been left to us by our predecessors as an inheritance. The Germans in those acquired treasures of the human mind are true proprietors. Those who depend on their own natural understandings alone are mere sojourners in comparison with them.

To be continued …

August Wilhelm von Schlegel

Goethe: Pleasures of the Mind

To strange conceits oft I myself must own…

For otherwise the pleasures of the mind

Bear us from book to book,

From page to page.

Then winter’s night grows cheerful;

Keen delight warms every limb;

And ah! when we unroll

Some old and precious parchment,

At the sight

All heaven itself descends upon the soul!

Goethe’s Faust

Excerpt, the 1850 Swanwick translation.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1775

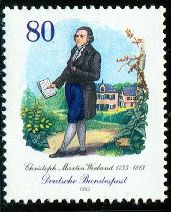

The Volksmärchen of Musäus 3/3

The Chronicles of the Three Sisters, Part 3 of 3

Excerpt from the German of Musäus: “The Legend of Rubezahl and Other Stories.” Editor C.M. Wieland. The 1845 William Hazlitt translation.

“Of a sudden the fish plunged under water, and the boat was again set afloat, but a moment after the monster of the lake re-appeared on its surface, and opening a hideous throat as big as a moderate-sized crater, from its dark abyss, as from a subterraneous vault, sounded forth deep and distinct these words: “Audacious fisher! How durst thou thus murder my subjects? Thou canst only atone for such an outrage with thy life!”

The Count was by this time so used to such adventures, that he knew exactly how to behave himself. Speedily recovering from his first alarm, when he thus knew the fish would be willing to listen to reason, he answered quite boldly: “Master Behemoth, do not forget the rites of hospitality; grant me a dish of fish out of your pond, and if you will favor me with a visit, my kitchen and cellar shall be open to you in return.”

“Stay, stay,” replied the monster, “we are not quite such good friends as all that; know’st thou not might is right; that the strongest eats the weakest? Thou stealest my subjects to swallow them, and I will swallow thee!”

Hereupon the grim fish opened his jaws still wider. as if he would swallow man and boat and trout and all. “Ah, spare my life! Spare my life,” cried the Count. “You see I am but a sorry breakfast for your whaleship’s stomach.”

The enormous fish seemed to consider awhile. “Well,” said he, “I know thou hast a pretty daughter, promise her to me for a wife, and take thy life in exchange.”

When the Count heard the fish take this tone, he laid aside all trace of fear. “She is quite at your service,” said he. “You are a gallant son-in-law to whom no honest father could refuse his child. But what will you lay down for your bride, according to the custom of the land?”

” I have neither gold nor silver,” answered the Fish, “but at the bottom of the lake lies a great treasure of pearl shells. Thou hast only to ask and to have.”

“Done,” replied the Count. “Three bushels of pearls are next to nothing for a pretty bride.”

“They are thine,” said the Fish, “and mine the bride; in seven months I shall fetch my darling home.”

Hereupon he beat the waves lustily with his tail and sent the boat ashore.

The Count took his trout, had them boiled, and with the Countess and the beautiful Bertha enjoyed the Carthusian meal exceedingly. The poor girl little dreamed how dear this meal was to cost her.

Well, the moon increased and diminished six times, and the Count had nearly forgotten his adventure, but as she became rounder and rounder for the seventh time, he thought of the impending catastrophe, and in order not to witness it, slipped away on a little excursion into the country. At the sultry hour of noon, on the day of the full noon, a gallant band of knights galloped up to the castle gates. The Countess, alarmed at the presence of so many strange visitors, hesitated whether to admit them or not; however, when a knight, well known to her, announced himself, she no longer objected.

He had often, in the days of their prosperity and profusion, attended the tournaments at the castle, had manifested rare skill in the joust, had received many a prize from the fair Bertha’s hand, and led off many a dance with her; but at the time of the change of the Count’s fortune, he had disappeared with the other knights. The worthy Countess was ashamed of having her poverty exposed to the noble chevalier and his suite, for she had nothing to serve up for their refreshment.

He, however, accosted her in a most friendly manner, and requested nothing but a draught of pure water from the castle well, just as he used to do erewhile, for he had never drunk wine , and had, indeed, been therefore called in joke the Water Knight.

The fair Bertha hastened, at her mother’s bidding, to the well, filled a jug, then poured its sparkling contents into a crystal cup, and, after putting it to her lips, presented it to the Knight. He received it from her delicate hand, and placing his mouth to the spot where her coral lips had touched the vase, pledged her with ineffable delight.

The Countess meantime was in the greatest embarrassment at not being able to offer her guest anything for breakfast; at length she recollected that there was a juicy water melon, just ripe, in the castle garden. She ran to the spot, and in a moment had plucked the melon and laid it upon an earthen plate, decked with vine leaves and the most odoriferous flowers as an offering to their guest. On returning from the garden, she found the court yard empty and silent, without either horses or horsemen, and going in doors she saw as little neither knight nor squire.

In terrible affright, she called for her daughter, Bertha; there was no answer; she sought for her all over the house; no daughter was to be found. In the hall was placed three bags, made of new canvas, which she had not remarked in her first alarm, and which felt from without as if they were filled with peas. Her affliction did not allow her to search further.

The good mother gave herself over to grief, weeping aloud till evening, when her husband returned and found her in terrible distress. She could not conceal from him what had happened though she would have fain done so, for she dreaded his reproaches for having let an unknown knight into the castle, who had been thus enabled to carry off their beloved daughter. But the Count, who comforted her most affectionately, seemed most interested in the bags of peas she had mentioned, and going out forthwith to look at them, opened one in her presence.

What was the astonishment of the afflicted Countess when there rolled out fine pearls, as large as the big peas in the garden, perfectly round, delicately pierced, and of the purest water. She clearly perceived that her daughter’s ravisher had paid every maternal tear with a pearl, and, imbued with an exalted opinion of his rank and riches, was consoled that this son-in-law was not a monster, but a stalwart and and stately knight, an error which the Count took care not to rectify.

The parents, it is true, had now parted with all their beautiful daughters, but in return they were possessed of an immense treasure. The Count soon converted a portion of it into money. From morning to night, the castle was swarming with merchants bargaining for the precious pearls. The Count redeemed his towns and estates, let his castle in the woods, and returned to his former capital where he resumed once more his princely state. No longer, however, as a reckless spendthrift but as a hospitable dignitary of the empire: for he had no more daughters left to barter away. The noble couple were now exceedingly well off, but the Countess could not get over the loss of her daughters; she constantly wore mourning and hardly ever smiled.

For a long time, she hoped to see her Bertha again, with the wealthy Knight of the Pearls, and as often as a stranger was announced at their court, she thought it was her son-in-law returning. At last the Count , who could not find it in his heart to feed these fallacious hopes any longer, confessed to her that this magnificent son-in-law was none other than an abominable fish.”

End of Excerpt and Book 1 of 3

“The Chronicles of the Three Sisters”

But, of course, not the end of the story!

The Volksmärchen of Musäus

The Volksmärchen of Musäus 2/3

The Chronicles of the Three Sisters, Part 2 of 3

Excerpt from the German of Musäus: “The Legend of Rubezahl and Other Stories.” Editor C.M. Wieland. The 1845 William Hazlitt translation.

“All is fish that comes to net for poor people. When Papa found that the trade in his daughters was so profitable, he consoled himself for their loss. This time he went home in capital spirits, and carefully concealed his adventure, partly to avoid the reproaches which he dreaded from the Countess, and partly not to afflict his dear girl before the time came. For appearance sake, he made a great lamentation about the lost falcon, which he said had flown away. Miss Adelheid was the cleverest spinster in all the land. She was also an excellent weaver, and had just then cut from the loom a valuable piece of linen, as fine as cambric, which she bleached on a grass plat not far from the castle. Six weeks and six days flew by without the beautiful spinster having the slightest misgiving of the fate that awaited her.

Her father, indeed, who began to be somewhat downhearted as the time fixed for fetching her away drew nigh, but privately given her many a hint of it, either relating some ominous dream he had had, or reminding her of the long since forgotten Wulfild; but Adelheid, who was of a light joyous turn of mind, only thought it was her father’s heavy temperament that put these hypochondriacal whimsies into his head. And so, on the seventh day of the seventh week, she slipped away as usual, at early dawn, light as air, to the bleaching ground, and spread out her piece of linen, that it might get saturated with the dew. When she had arranged this matter, and was looking about her a little, she perceived a splendid procession of knights and pages prancing along towards the castle.

As her toilet was incomplete, she hid herself behind a wild rosebush that was in full bloom, whence she peeped out to see the gorgeous cavalcade as it passed. The handsomest knight of the whole throng, a slim young man with open vizer, bounded towards the rosebush, and said in a very gentle voice: “I seek thee, I see thee, beautiful beloved; hide not thyself, but haste , that I may put thee behind me on the horse, thou lovely Eagle’s bride.”

Adelheid knew not what in the world to think when she heard these words. The handsome knight pleased her well enough, but the title “Eagle’s bride,” made the blood freeze in her veins; she sank fainting to the ground, and when she came to her senses, she found herself in the arms of the amiable knight on her road to the forest.

Meantime, Mamma had prepared breakfast; and, as Adelheid did not make her appearance , she sent her youngest daughter to see where she was. As the messenger did not return, Mamma thought this boded no good, and went to see why her daughter stayed so long; but Mamma did not return either. Papa perceived what was going on; his heart went thump! thump! and he slunk off to the grass plat where both Mamma and daughter were still looking for Adelheid; and anxiously calling out her name; and he, too, set to work shouting at the top of his voice, though he knew perfectly well that all shouting and seeking were equally fruitless. By and by, his road took him near the wild rosebush where he perceived some objects glittering which, on examining them more closely, he found to be a couple of golden eggs, each of a hundred weight. He could now no longer help telling his wife their daughter’s adventure.

“O shameless soul kidnapper!” she cried; “O vile daughter murderer! Is it thus thou infamously sacrifice thine own flesh and blood to Moloch, for the sake of filthy lucre?”

The Count, who had, however, but an indifferent stock of eloquence, defended himself for awhile as best he might, offering as an excuse for his conduct the pressing danger her life was in at the time. The inconsolable mother would not hear a word he had to say, but continued heaping the bitterest reproaches upon him. He therefore adopted the most infallible method of putting an end to all contests — he held his tongue, and let his lady talk as long as she pleased, and meantime proceeded to secure the golden eggs by rolling them slowly before him to the castle. Then he wore family mourning for three days, for decency’s sake; after which he thought of nothing else than resuming his former life.

In a short time, the castle again became the abode of pleasure. the Elysium of hungry, sponging parasites. Balls, tourniquets and splendid feasts became every-day events. Miss Bertha shown as brightly in the eyes of the stately knights who repaired to her father’s court, as the silver moon does to the sentimental rambler on a serene summer’s night. It was she who bestowed the prize at every tournament, and led off the dance in the evening with the victorious knight. The noble hospitality of the Count, and the rare beauty of his daughter, brought to their balls knights of noble birth, from the most distant lands. Of these a dozen at the least essayed to win the heart of the rich heiress; but amongst so many suitors the choice was difficult, where each new comer seemed to surpass his predecessor in nobility and good looks.

The beautiful Bertha chose and doubted, chose and doubted so long that at last the golden ingots , to which the Count had by no means applied the file sparingly, had dwindled down from the size of roc’s eggs to mere hazel nuts.

The Count’s finances having thus again fallen into their former low estate, the tournaments were given up, knights and squires disappeared, the castle again became a desert, and the distinguished family again returned to their potato diet. The Count once more wandered the fields, in doleful dumps, longing for a fresh adventure, but meeting with none for a long time, though he went as near the forest as he dared.

One day he followed a covey of partridges so far that he came close upon the enchanted wood, and although he did not venture in, he kept walking along its skirts for some way, till, lo and behold! he saw before him an immense piece of water he had never set eyes on before, beneath whose clear silver surfaces countless trout were swimming about. The discovery delighted him very much, for the pond had a most unauspicious appearance; he, therefore, hastened home and made a net, and the next morning, betimes, there stood he on the shore, ready for fishing. To complete his good fortune, what should he see among the reeds but a little boat with an oar. Jumping into this, he rowed vigorously about the pond, and then casting his net caught more trout at one draught than he could possibly carry, with which he made for the shore, delighted with his prize.

About a stone’s throw from land, however, the boat suddenly stopped in its course, and remained immovable as if it had stuck to the bottom of the pond. The Count thought this must be the case as he tugged with all his might to set it afloat again, but in vain. The waters barred its progress on every side, above whose surface the vessel seemed to be lifted high, higher, as though it were perched on a rock. The poor fisherman could not at all tell what to make of it, and felt excessively uncomfortable. Although the boat was as if nailed to the spot, the banks appeared to recede on each side, the pond extended itself out into a great lake, the waves began to swell and roar and foam, and he perceived to his amazement and alarm that he and his boat were upon the back of an enormous fish. He resigned himself to his fate, though of course not a little anxious to see what turn things would take.”

To be continued…

The Volksmärchen of Musäus

The Volksmärchen of Musäus 1/3

This work is, of its kind, one of the very best

that the last quarter of the 18th Century has produced.

C.M. Wieland

Weimar, June 12th, 1803

The Chronicles of the Three Sisters

Excerpt from the German of Musäus: “The Legend of Rubezahl and Other Stories.” Editor C.M. Wieland. The 1845 William Hazlitt translation.

Part 1 of 3

“There was once a very, very rich Count who wasted his substance by the most lavish expenditure. He lived in king-like style, keeping open house every day in the year. Whoever claimed his hospitality, whether knight or squire, was feasted sumptuously for three long days; and no guest but left him delighted with the entertainment he had received. He was terribly fond of gambling; his Court swarmed with golden-haired pages, running footmen, and heyducs in splendid liveries, and his stables absolutely ran over with countless horses and dogs. His treasures at last became exhausted by all this perfusion. He mortgaged one town after another, sold his jewels and plate, and dismissed his servants; and of all of his vast wealth, nothing remained but an old castle in the woods, a virtuous wife, and three wondrously beautiful daughters.

To this castle went he, abandoned by all the world. The Countess herself and her daughters saw to the kitchen, and as none of them knew anything about cookery, they could only boil potatoes. This frugal fare suited Papa’s taste so little that he grew peevish and ill-tempered, and went about the great rambling, empty house swearing and storming, till the bare walls rung again with his passion. One fine summer’s morning he snatched up his hunting spear in a fit of sheer spleen, and set off to the forest to strike a deer, or even any smaller game, so that he might have a more savoury meal than usual.

Of this forest, there ran a tale that it was haunted by ungentle spirits. Many a wanderer had lost his way in its intricacies and never been seen again, having either been throttled by wicked gnomes or torn to pieces by wild beasts. The Count did not at all believe in supernatural agency, and had consequently no fear of invisible enemies, gnomes or hobgoblins; he made his way stoutly over hill and dale into the forest, where he struggled on, through the thickets, without meeting the game he was in search of, until he was thoroughly tired. He then sat down under a fine tall oak, and drew from his pouch a few boiled potatoes and a little salt, his whole day’s stock of provisions for the mid-day’s repast.

On raising his eyes by chance just before he began, lo and behold! a terrible great bear was approaching. The poor Count was monstrously frightened at the site; escape he could not, and he was not equipped for a bear-fight. However, in this extremity he did all he could; he grasped his spear, and stood in an attitude to defend himself as best he might. The monster came nearer and nearer, and then suddenly stopped short and distinctly growled out these words: “Robber! Plunderest thou my honey-tree? Thou canst only atone for such outrage with thy life.”

“Oh, oh!” cried the Count pitifully; “Pray don’t eat me up, Master Bear; I don’t want your honey at all; I am an honest knight. If you are hungry, pray be pleased to take pot-luck with me. “

So saying, he dished up all the potatoes in his hunting cap for the Bear’s acceptance. But the latter scorned the Count’s fare, and growled out again, in a most surly tone: “Wretch, think’st thou to redeem thy life at such a price. Instantly promise me thy eldest daughter, Wulfild, for my wife, or I’ll devour thee on the spot!”

In his fright, the Count would have promised the amorous Bear all of his daughters, and his wife in the bargain, if he required it, for necessity has no law.

“She shall be yours, Master Bear,” said the Count, beginning to recover himself a little; but on condition,” he added cunningly, “that you ransom the bride according to the custom of the land. and come yourself to take her home.”

“Done,” said the Bear, “shake hands upon it.” And he presented him his rough paw. “In seven days I will come and ransom her for a hundred weight of gold, and fetch my darling home.”

“Done!” said the Count.

And thereupon they parted in peace; the Bear returning leisurely to his den, and the Count losing no time in getting out of the terrible forest, reached home at starlight, utterly worn out.

It stands to reason that a Bear who can talk and traffic rationally, like a man, is not a natural but an enchanted bear. This the Count made up his mind to; and he accordingly determined to chouse his shaggy son-in-law elect, by entrenching himself in his stronghold, so that it would be impossible for the Bear to enter, when he should come to fetch his bride on the appointed day. “For,” thought he, “though an enchanted bear may have the gift of speech and reason, still he is after all only a bear, and has in all other respects merely the qualities of an ordinary animal; so that he can’t fly like a bird, or creep through the keyhole of a locked up room like a spirit, any more than he can pass through the eye of a needle.”

On the following day be acquainted his wife and the young ladies with his adventure in the forest. Miss Wulfild swooned away with horror, when she heard she was to be married to a frightful bear; Mamma wrung her hands and wept aloud; and the other sisters shivered and shook with woe and wonder. As for Papa, he went out and surveyed the walls and the moat that surrounded the castle, and examined the iron gate to see that it was firm and fast; he then raised the drawbridge, closed every entrance, and lastly went up into the watch-tower where he found a little chamber built in the wall under the battlements, and there he shut up the young lady, who tore her fine flaxen hair, and nearly cried her blue eyes out of her head.

Six days passed away; the seventh had just dawned, when a loud clattering noise proceeded from the forest, just as if the Wild Hunt was abroad. Whips cracked, horns sounded, horses pranced and wheels rattled. A splendid state carriage, surrounded by horsemen, rolled over the plain, and speedily reached the castle door. All the bolts shot back, the door flew open, the drawbridge fell, and a young prince, handsome as the day, and dressed in velvet and in cloth of silver, stepped out of the carriage. Round his neck, thrice wound, was a chain of gold, solid enough to bear a man’s weight; on his hat he wore a string of pearls, and diamonds that would have dazzled your eyes to look at; the clasp that fastened his ostrich plume was worth a dukedom at least. He flew up the winding staircase with the rapidity of a whirlwind, and in the twinkling of an eye brought down the trembling bride in his arms.

The uproar awakened the Count from his morning’s slumber; he jumped out of bed and threw open the window; and when he saw the horses and the carriage, and the knights and the troopers in the courtyard, and his daughter in the arms of a strange man, who was lifting her into the bridal coach, which then set off with the rest of the party through the castlegate, a pang shot through his heart, and he cried out in a lamentable tone: “Farewell, daughter mine! God be with thee, thou Bear’s bride!”

Wulfild heard her father’s voice, and waved her handkerchief from the carriage-window, as if to bid adieu.

The parents were in utter consternation at the loss of their daughter, and looked at each other in moot dismay. Then Mamma would not believe her eyes, and determining that the whole affair was delusion and witchcraft, snatched up her bunch of keys, ran up the watch-tower and opened her cell, where she found neither her daughter nor any of her clothes; but on the table lay a silver key, of which she took possession; as she chanced to look through the window she saw a cloud of dust in the distance, towards the eastern horizon, and heard the clatter and acclamations of the bridal party, till they entered the forest. Full of sorrow, the Countess came down from the tower, put on morning, strewed her head with ashes, and wept for three whole days, her husband and daughters sharing to the full her grief and lamentations. On the fourth day, the Count left the house of mourning, in order to have a little fresh air, when as he crossed the court yard, what should he see but a beautiful great ebony chest standing there, well secured and very heavy. He readily guessed what it contained. The Countess gave him the key, he opened it, and found therein a hundred weight of gold, all in doubloons and one coinage. Joyful at this discovery, he forget his troubles, bought horses and falcons, and fine clothes for his wife and two dear daughters, hired servants, and set to work again guzzling and gormandizing, till he had drained the chest of its last doubloon. Then he ran into debt, and all his creditors came like a flock of harpies, and regularly cleared out the castle, leaving nothing in it but an old falcon. The Countess and her daughters were again obliged to boil potatoes, while the husband wandered about in the fields all day long with his bird, overcome with ennui and vexation.

One day that he had cast his hawk, it rose high up in the air and would not return to his hand, call as he might. The Count followed his flight, as well as he could, over the vast plain; the bird went on straight toward the dread forest, which the Count did not choose foolishly to tempt again, and accordingly he gave up his dear friend as lost. All of a sudden a mighty Eagle rose among the forest trees, and pursued the falcon, which no sooner saw that it was threatened by an enemy so much stronger than itself, than it flew with the speed of an arrow back to its master to seek for protection. But the Eagle darted down from aloft, and striking one of its vast talons into the Count’s shoulder, crushed the trusty falcon with the other. The Count, at once amazed and alarmed, endeavored with his spear to free himself from the feathered monster, striking and thrusting fiercely at his foe. But the Eagle seized the hunting spear, and having shivered it like a reed, screamed these words loudly into his ear: “Audacious creature, how dar’st thou disturb my airy dominions with thy sport? Thou canst only atone for such an outrage with thy life!”

The Count at once guessing from the bird’s speech what sort of adventure was likely to ensue, took courage and said: “Softly, Sir Eagle, softly! What harm have I done you? My falcon has paid for his sins, and I’ll make him over to you, to satisfy your hunger.”

“No,” screamed the Eagle; “I happen just today to have a fancy for man’s flesh, and you seem a nice fat morsel.”

“Pardon me, Master Eagle,” cried the Count in agonized alarm, “ask what you will of me, and you shall have it; only spare my life!”

“Well,” replied the horrible Eagle after a pause. “I’ll take you at your word; you have two handsome daughters, and I want a wife. Promise me your Adelheid in marriage, and I’ll let you go in peace, and ransom her with two golden ingots of a hundred weight each. In seven weeks, I shall fetch my darling home.”

So saying the monster soared toward the sky, and disappeared into the clouds.”

To be continued…

The Volksmärchen of Musäus

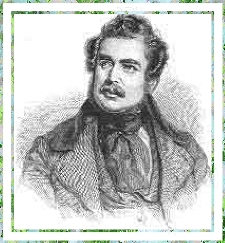

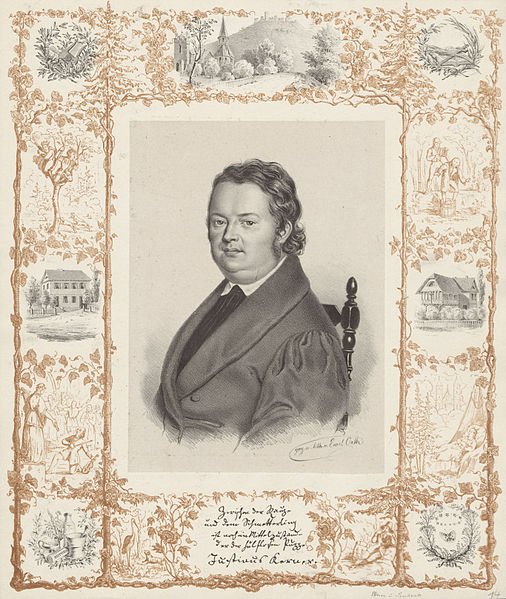

Heinrich Heine on Ludwig Tieck, Pt. I

Their words have been honored by such Lieder composers as Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn and Brahms. For more information on the music inspired by Heine and Tieck, as well as other fine German poets, I invite you to visit Emily Ezust’s Lied & Art Song Texts Page. To better appreciate the challenges of their time and circumstance, please see previous post, “Young Germany and Heinrich Heine.”

“You could scarcely fail,” replied the stranger.

“Whoever knows how to seek,

Whoever feels his heart drawn toward it with a

Right inward longing

Will find friends of former ages there,

And glorious things, and all that he wishes most.”

Ludwig Tieck

“After the Schlegals, Ludwig Tieck was the most effective author of THE ROMANTIC SCHOOL. For it, he fought, thought and sang. He was a poet, a name which neither of the Schlegals deserved; for he was a true son of Phoebus Apollo, and, like his ever-youthful father, he bore not only the lyre but the bow, with a quiver full of rattling, ringing arrows. He was, like the Delphian god, intoxicated with lyrical fire and critical cruelty. And when, like him to, when he had pitilessly flayed alive some literary Marsyas he merrily grasped with bloody fingers the golden chords of his lyre and sang a sweet song of love.

The poetical polemic which Tieck waged in dramatic form against the adversaries of the school belongs to the most remarkable curiosities of our literature. They are satirical plays, which are generally compared with the comedies of Aristophanes. Yet they differ from the latter almost as much as a tragedy by Sophocles differs from Shakespeare. If the ancient comedies had the same cut and style, the strictly drilled step, and the exquisitely metrical language of ancient tragedies, so that they might pass for parodies, so are the dramatic satires of Tieck cut in as original and strange a manner; just as Anglicanly irregular and as metrically capricious as the tragedies of Shakespeare.

Was this form invented by Tieck? No; for it existed already among the people of Italy. He who understands Italian might get a tolerably correct idea of the dramas of Tieck if he will dream himself into the chequered-bizarre, Venetian-fantastic fairy tale comedies of Gozzi, mixed with a little German moonshine. In fact, Tieck took many of his masks from this merry child of the Lagunes. Following his example, many German poets have mastered the same form; hence, we have had comedies whose comic effects were not produced by a single fanciful character or a gay intrigue, but where we are transported at once into a wild and merry world, where animals talk and act like men, and where chance and caprice take its place in the natural order of things.

This we also find in Aristophanes. But the latter chose this form to reveal to us his profoundest views of the world, as , for instance, in the “Birds” where the maddest efforts of mankind, their desire to build the grandest castles in the air, their defiance of the eternal gods, and the vain joy of their triumphs, are set forth in the most ludicrous caricatures.

And it was that which made Aristophanes so great, because his views of the world were so great, because they were grander and more tragic than the tragedian himself; because his comedies were really jesting tragedies. Take, for example, his Paisteteros, who is not shown up in his ridiculous worthlessness at the end of the play, as a modern poet would have planned it. On the contrary, he woos and wins the beautiful, marvellously mighty Basilea; he sores with this heavenly bride to his city in the air; the gods are compelled to obey him, folly celebrates its marriage with power, and the play ends with joyous marriage-hymns.

Can there be, for any reasonable man, anything more cruelly tragic than this victory and triumph of folly? Our German Aristophanes do not rise so high; they refrain from such lofty views of life; they manifest the utmost modesty as regards discussing those very important relations of man, politics and religion; they only venture on the theme which Aristophanes himself has treated in the “Frogs” as a subject of satire – the stage itself – and they have mocked with more or less cleverness its failings.

Still we must consider the politically enslaved condition of Germany. Our wits, restrained from ridiculing real princes, made up for it by attacking kings of the theatre and queens of the coulisses. We, who were almost destitute of political journals which discussed public affairs, were all the more blessed with countless aesthetic journals, containing nothing but idle tales and theatrical criticisms, so that anyone who saw our newspapers might well suppose that the whole German race consisted of chattering nursery maids and theatrical critics.

And yet it would have been unjust.

How little content we were with such miserable scribbling appeared immediately after the Revolution of July, when it seemed as if free and bold words might be uttered in our own dear native land. There sprung up all at once newspapers which criticized the good and bad acting of real kings, and many of them who had forgotten their parts were hissed in their own capitals.

Our literary Scheherazades, who had hitherto put the public, that plump Sultan, to sleep with their little tales, were now silent; the actors saw with amazement the pit empty, however divinely they played, and even the reserved seats of the terrible town-critics were often vacant. Once the good heroes of boards always complained that they were continually subjects of public conversation, and that even their domestic affairs were discussed in the journals. But what was their horror when the awful truth flashed upon them that nobody now cared what they did!

In fact, when the Revolution broke out in Germany, there was an end to theatres and and dramatic criticism, and the terrified feuilletonists, actors and critics apprehended – and justly – that “Art was going to the dogs.” But this great calamity was fortunately averted from our native land by the wisdom and power of the Frankfort Diet.

There will be, let us hope, no revolution in Germany. We are protected from the guillotine and all the terrors of freedom of the press . Even the Chamber of Deputies, whose competition so greatly injured the regularly licensed theatres, is done away with; and art is saved! Just now they are doing all they can for art, especially in Prussia. The museums gleam with all the splendours of color, the orchestras sound, the ballet-girls leap their loveliest and liveliest entrechats, and a thousand and one novels enrapture the public, and theatrical criticism blooms again.

Justinus relates in his “Histories” that when Cyrus had quieted the revolt of the Lydians , he succeeded in taming stubborn, liberty-loving spirit by inducing in them an interest in the fine arts and other pleasant things. So there was nothing more heard of Lydian liberty or rebellion, but all the more famously did the Lydian restaurant-keepers, panders and artists flourish.

Now there is in Germany rest and repose. Theatrical criticism and novels are to the fore, and as Tieck exceeds in both, all friends of art pay him the tribute due. He is, in fact, the best novelist in Germany. Yet all his works are not of equal worth or of the same kind. We can distinguish in him, as in painters, many manners.

His first was altogether that of the old school. Then he wrote to order, and by command of a bookseller, who was no other than the Nicolai himself,the most self-willed of champions of enlightenment and humanity, the greatest enemy of superstition, mysticism and romance. Nicolai was an indifferent writer, a prosaic old wig, who often made himself ridiculous by scenting Jesuitism. But we, the later born, must admit that old Nicolai was a throughly honest man, who meant well for the German race, and who in the holy cause of liberty did not dread that cruelest of all martyrdoms, ridicule. I was told in Berlin that Tieck once lived in Nicolai’s house, one story above the latter, and so the modern time walked over the head of the old.

The works which Tieck wrote in his first style, mostly tales and long novels, among which “William Lovell” is the best, are very insignificant and without poetry. It would seem as if the rich poetic nature of this man was frugal and stinted in his youth, and that he saved up all his spiritual wealth for a later time. Or was Tieck himself ignorant of the treasure which was in him, and were the Schlegals needed to discover it with their divining rod? For as soon as he came in touch with them, all the riches of his imagination, his deep feeling and his wit. at once showed themselves. Diamonds gleamed, the purest pearls rolled out in streams, and over all flashed the ruby, the fabulous carbuncle gem of which romantic poets have often said and sung. This rich breast was the real treasury whence the Schlegals drew the funds for their literary campaigns. Tieck had to write for the school the satirical which I have mentioned, and prepare according to the new aesthetic recipes many poems of every kind. This is his second style.

His best productions in it are “The Emperor Octavian,” “The Holy Genofeva,” and “Fortunatus,” three dramas which take their names from chapbooks. The poet has given to these old tales, which have ever been dear to the German world, new and costly clothing. Honestly speaking, I prefer them in their old naive, true-hearted form. Beautiful as Tieck’s “Genofeva” may be, I love far better the old Volkbuch, very badly printed at Cologne on the Rhine, with its rude woodcuts, in which it is touching to see the poor naked Countess Palatine, with only her long hair for chaste clothing, while her little Schmerzenreich is nursed at the teats of a pitying doe.

Far more precious than these novels are the novels which Tieck wrote in this, his second manner. These too are mostly taken from the old popular legends. The best are “The Blond Eckbert” and “The Runenberg.” In these compositions, we feel a mysterious depth of meaning, a marvelous union with Nature, especially with the realm of plants and stones. The reader seems to be in an enchanted forest; he sees subterranean springs and streams rustling melodiously, and his own name whispered by the trees. Broad-leaved clinging plants wind vexingly about his feet, wild and strange wonder- flowers look at him with varicoloured longing eyes, invisible lips kiss his cheeks with mocking tenderness, tall mushrooms like golden bells grow singing about the root, great silent birds cradle themselves on the boughs, and nod adown with their cunning long bills.

All breathes – lurks – is thrilling with expectation, when suddenly the soft tune of a hunter’s horn is heard, and a beautiful lady with waving plumes on her cap, a falcon on her wrist, rides past on a white palfrey. And this fair dame is as bright and blond and violet-eyed, as smiling and yet serene, as true and yet as ironic, as chaste and yet as passionate, as the imagination of our glorious Ludwig Tieck. Yes! his fantasy is a wondrous winsome damoiselle of high degree, who in an enchanted forest hunts fabulous creatures – perhaps the rare unicorn which can be caught only by a pure maid.”

To be continued tomorrow in Part II.

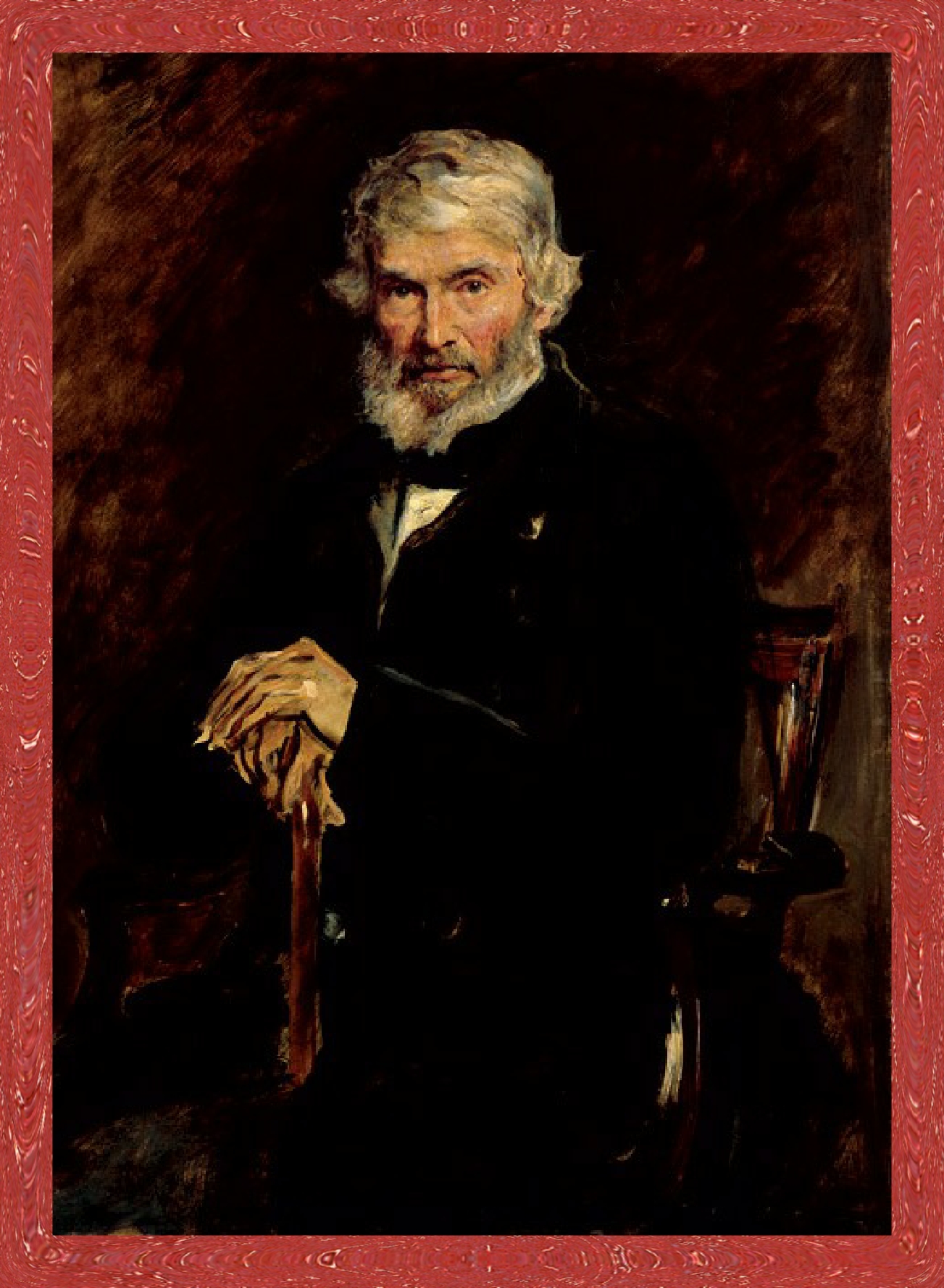

Johann Ludwig Tieck

Madame de Staël on “The Robbers”

See here! See here!

The laws of the world have become mere dice-play;

The bonds of Nature are torn asunder.

The Demon of Discord has broken loose

And stalks about triumphant!

Schiller

My newest book has arrived and I am pleased! The 1799 Render translation of Schiller’s first drama, “Die Räuber” ( published in 1781; first translated as The Robbers in 1792). At two hundred and nine years of age, the volume is a beauty! Bound in contemporary green calf, its spine is richly decorated and lettered in gilt (title and author vibrant!), its boards distinctively bordered in gilt and blind, with green marbled edges and end-papers, pages clean and bright, and a handsome frontispiece by Nagle!

Just hold an old book in your hand. Listen! It will whisper to you of ages past, if only you have the heart to hear!

But now, Comments from another antique source … DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation).

Schiller, in his earliest youth, possessed a fervour of genius, a kind of intoxication of sentiment, which misguided him. The “Conspiracy of Fiesco,” “Intrigue and Love,” and , lastly, “The Robbers,” all which have been performed in the French theatre, are works which the principle of art, as well as those of morality, may condemn; but from the age of five and twenty, his writings were pure and severe. The education of life depraves the frivolous, but perfects the reflecting mind.

“The Robbers” has been translated into French, but greatly altered; at first they omitted to take advantage of the date, which affixes an historical interest to the piece. The scene is placed in the 15th century, at the moment when the perpetual peace, by which all private challenges were forbidden, was published in the empire. This edict was no doubt productive of great advantage to the repose of Germany; but the young men of birth , accustomed to live in the midst of dangers, and rely upon their personal strength, fancied that they fell into a sort of shameful inertness when they subjected themselves to the authority of the laws. Nothing was more absurd that this conception; yet, as men are generally governed by custom, it is natural to be repugnant even to the best of changes, only because it is a change. Schiller’s Captain of the Robbers is less odious than if he were placed in the present times, for there was little difference between the feudal anarchy in which he lived, and the bandit life which he adopted; but it is precisely the kind of excuse which the author affords him, that renders his piece the more dangerous. It has produced, it must be allowed, a bad effect in Germany. Young men, enthusiastic admirers of the character and mode of living of the Captain of the Robbers, have tried to imitate him.

Their taste for a licentious life they honoured with the name of the love of liberty, and fancied themselves to be indignant against the abuses of social order, when they were only tired of their own private condition. Their essays in rebellion were merely ridiculous, yet have tragedies and romances more importance in Germany than in any other country. Every thing there is done seriously; and the lot of life is influenced by reading such a work, or seeing such a performance. What is admired in art, must be imitated into existence. Werther has occasioned more suicides than the finest woman in the world; and poetry, philosophy, in short all the ideal, have often more command over the Germans, than nature and the passions themselves.

The subject of “The Robbers” is the same with that of so many other fictions, all founded originally on the parable of the Prodigal. There is a hypocritical son, who conducts himself well in outward appearances, and a culpable son, who possesses good feelings among his faults. This contrast is very fine in a religious point of view, because it bears witness to us that God reads our hearts; but is nevertheless objectionable in inspiring too much interest in favor of a son who deserted his father’s house. It teaches young people with bad heads universally to boast of the goodness of their hearts, although nothing is more absurd than for men to attribute to themselves virtues, only because they have defects; this negative pledge is very uncertain, since it never can follow from their wanting reason that they are possessed of sensibility: Madness is often only an impetuous excess of self-love.

The character of the hypocritical son, such as Schiller has represented him, is much too odious. It is one of the faults of very young writers to sketch with too hasty a pencil; the gradual shades in painting are taken for timidity of character, when, in fact, they constitute a proof of the maturity of talent. If the personages of the second rank are not painted with sufficient exactness, the passions of the chief of the robbers are admirably expressed. The energy of this character manifests itself in turns in incredulity, religion, love and cruelty. Having been unable to find a place where to fix himself in his proper rank, he makes to himself an opening through the commission of a crime; existence is for him sort of a delirium, heightened sometimes by rage, and sometimes by remorse. The love scenes between the young girl and the chief of the robbers, who was to have been her husband, are admirable in point of enthusiasm and sensibility; there are few situations more pathetic than that of this perfectly virtuous woman, always attached from the bottom of her soul to him whom she loved before he became criminal. The respect which a woman is accustomed to feel for the man she loves is changed into a sort of terror and of pity; and one would say that the unfortunate female flatters herself with the thought of becoming the guardian angel of her guilty lover, in heaven, now when she can never more hope to be the happy companion of his pilgrimage on earth.

Schiller’s play cannot be fairly appreciated by the French translation. In this they have preserved only what may be called the pantomime of action; the originality of the characters has vanished, and it is that alone which can give life to fiction; the finest tragedies would degenerate into melo-drames, when stripped of the animated colouring of sentiments and passions. The force of events is not enough to unite the spectator with the persona represented; let them love, or let them kill one another, it is all the same to us, if the author has failed of exciting our sympathies in their favour.

Madame de Staël

E.T.A. Hoffmann’s “Blanche of Aquitaine”

Of course, Hoffmann is the creator of the “The Nutcracker” and many other wonderful tales … much of his work challenging to find in translation. But, always, the antique volumes are my particular interest … and my greatest pleasure. “Blanche of Aquitaine, A Tale of the Days of Charlemagne” is a short story by E.T.A. Hoffmann I found published in London’s Novel Newspaper of 1841. Evocative in a way of Schiller’s “Don Carlos” and Byron’s “Parasina” … it’s a beautiful tale. And I would like to share an excerpt with you now…

The day arrived appointed for the ceremony. Early in the day, the gates of the City were thrown open. Nobles, with pompous retinues, and rustics, with their families, crowded the avenues. Greediness of spectacle has been common to all ages of the world. Church and convent bells were tolling; processions of the religious orders filled the streets with the sublime anthems appointed by the church; and the Gregorian chant resounded from the choir of the great chapel.

The emperor and his court, in their ceremonial costumes, entered the chapel by a private door, and occupied seats at the right of the altar; the emperor and queen were in position a little elevated, and in advance of their attendants. There was an unquietness in Charlemagne’s manner, and a shade to his brow, that indicated the yearning of his heart towards his son, and the reluctance with which he had submitted to the usage that imposed the humiliation of a public ceremony.

The doors were thrown open, and the eager crowd of spectators, marshalled by officers, were conducted to seats assigned them, according to rank. The chapel bell struck, and the prince, preceded by men-at-arms, and followed by a procession of monks from St. Alban’s, entered the grand aisle. His dress resembled that worn by his father in high festivals: A golden diadem, set with precious stones, bound in its circlet a head that looked as if it were formed to ennoble such an appendage; his buskins were thickly studded with gems – his tunic was of golden tissue – and his purple mantle fastened by a clasp of glittering stones. This royal apparel was meant in part to show forth the ambition that had o’erleaped itself, and, in part, to set the splendours of the world in overpowering contrast with the humility of the religious garb.

The prince advanced with a firm step. His demeanor showed, that if he had lost everything else, he had gained the noblest victory – victory over himself. There was nothing in his air of a crushed man; on the contrary, there was his usual loftiness, and more than his usual serenity. As men gazed at him, and saw the impress of his father on his mild majestic brow, they felt that nature had set her seal to his right of inheritance. He paused, as he reached a station opposite his father, signed to his attendants to stop, and turning aside, he knelt at his father’s feet. Their eyes met as tenderly as a mother’s meets her child. Charles stretched out his hand – Pepin grasped it, and pressed it to his lips. The spectators looked in vain for some sign of sternness in the father, and resentment in the son. Little did they dream that the father and son had met that morning, with no witness save the approving eye of Heaven; and had exchanged promises of forgiveness and loyalty, never to be retracted in thought, word or deed.

As the prince rose to his feet, his eye encountered the queen’s, flashing with offended pride; but hers fell beneath the steady overpowering glance of his, which said, “I am not yet so poor as to do you reverence.”

The emperor did not rebuke, or even seem to notice the omission; his eyes were riveted to the gracious tears his son had left upon his hand.

The devotions and pompous ceremonial proscribed by the Romish church were then performed. The prince then laid down his glittering crown, and exchanged his gorgeous apparel for the garb of the St. Alban’s monks, a russet gown fashioned at the waist by a hempen cord. It was noticed by the keenest observers that he did not lay aside his sword; but he might have forgotten it, or a soldier might be permitted to the very last to retain the badge of his honour and independence. A glow of shame shot over his face, as he bent his head to the humiliating rite of the tonsure; and the eyes of the truly noble were averted , as his profuse and glossy locks fell beneath the razor of the officiating priest. This initiatory rite performed, a hood was thrown over his head. and the soldier-prince was lost in the humble aspect of the monk of St. Alban.

But, of course, that’s not the end of the story <g>

E.T.A. Hoffmann

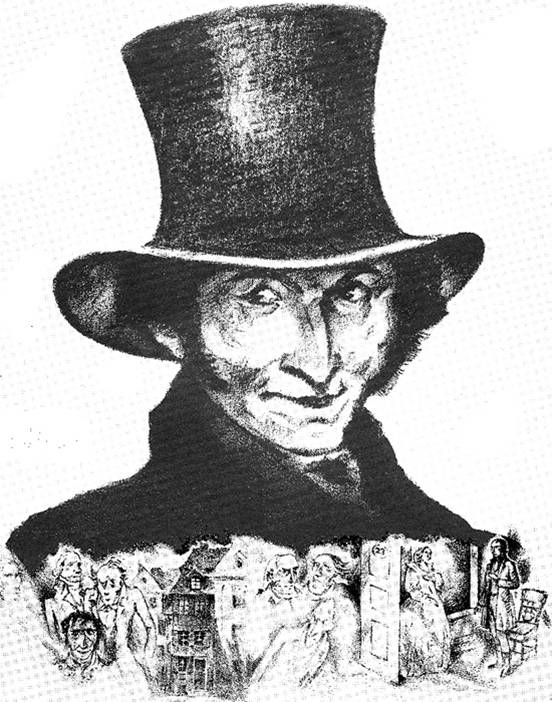

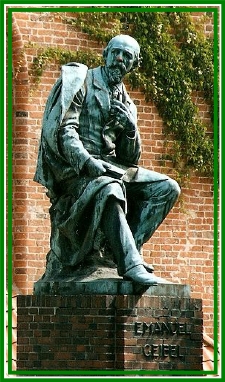

Schiller’s Die Räuber

I am better than my reputation … Schiller

I honor Friedrich Schiller … and possess most of his work in 19th Century translation. His words live in my heart still … and are part of who I am as a person today. And on its way to me now, I’m delighted to say … is a fine new addition to my beloved antique book collection: An earlier copy of “The Robbers.” The 1799 Render translation.

From http://worldroots.com/brigitte/schill1.htm:

A universal genius generally regarded as the greatest German dramatist, Friedrich Schiller dominates a period of German literary history as no one else before or since. Schiller revealed more vividly than any of his predecessors the power of drama and poetry to convey a philosophy; his works contain the strongest assertions of human freedom and dignity and the worth of the individual in all German literature.

To modern English-speaking people the mystique surrounding Schiller may seem hard to fathom. Yet to study how Germans perceive Schiller is to study how they perceive themselves. He appeared at a time when German literature was dominated by the monumental achievements of England, France, and Italy; there was even serious debate about whether the German language was a fit vehicle for literary expression. Schiller furnished proof of Germany’s high cultural achievement.

Schiller’s first drama was “Die Räuber” (1781; translated as The Robbers, 1792). Little is known about the genesis of the play other than that he had begun work on it when still a teenager. A vital, energetic, and troubling work, it soon caught the eye of Wolfgang Heribert von Dalberg, director of the Mannheim National Theater in the neighboring duchy of Hesse, who decided to bring it to the stage. The play was a sensation. Much of its appeal resides in Schiller’s choice of the archetypal theme of hostile brothers. The jealous and greedy Franz von Moor tricks his father, the ruling count, into disinheriting his elder brother, Karl, who is away at the university. He then imprisons his father and seizes the land and title for himself and tries to terrorize Karl’s beloved, Amalia, into concubinage. Learning of his disinheritance, Karl drops out of school and becomes the leader of a band of robbers. No ordinary hoodlum, he is consumed by a demonic craving for justice; he has the noble but misguided notion that he can right the wrongs of the world by taking the law into his own hands. But the frightening violence that attends each raid begins to plague his conscience. His final catastrophic effort to bring his brother to justice ends in Franz’ suicide and the deaths of the count, Amalia, and Karl’s closest friend. In the end Karl realizes that he has done more harm than good. His last act, turning himself in to the police, amounts to a cry from the heart for lost ideals.

The drama introduces two themes that were to occupy Schiller for the rest of his life. The first is that of the criminal hero, the man inspired by lofty goals who employs immoral methods to achieve them. The second is that of the idealistic reformer betrayed by institutionalized hypocrisy and greed; in his hero’s fall Schiller consistently underscores the futility inherent in the pursuit of ideals. The play also reveals Schiller’s innate grasp of what constitutes drama. As a piece of stagecraft Die Räuber has it all: sibling rivalry, armed robberies, an evil tyrant, a captive maiden, raging battles, tender love, and the conflict between good and evil. The language and the characterization are shamelessly overblown, but they matched the epic proportions of the action and struck a responsive chord in the viewers. The play was one of the most astonishing hits in the annals of the German stage, and the critics were no less enthralled than the public.

Madame de Staël

Traveling the

The Baroness Ann Louise Germaine de Staël-Holstein’s “De L’Allemagne.”