Category Archives: Tieck

Ludwig Tieck: “Legacy” Pt. 2

Excerpt, translated from the German by G. Greville Moore, 1883.

Chapter II

Edward went home in an indescribable anger. He entered furiously, slammed all the doors behind him, and hastened through the large apartments to a small back apartment, where in the twilight old Eulenbock was waiting for him, with a glass of wine.

“Here!” exclaimed Edward, “thou old sharp-nosed, wine-blotched scoundrel, is they daub back again. Sell it to the soap-boiler over there, who can make candles of it if the painting does not please him.”

“It were a pity for the good picture,” said the old painter, while he poured out a fresh glass of wine with the greatest sang froid. “Thou hast over-excited thyself, my friend. And the old man would not hear of the purchase.”

“Ruffian!” screamed Edward, in throwing down the picture violently, “for thy sake I have become a rogue! Insulted and mortified! Oh! and how ashamed of myself; my head and neck glowing that I should have allowed myself to tell such lies out of affection for thee.”

“They are no lies, my dear young man,” said the painter, while he unwrapt the picture; “it is as true a Salvatore Rosa as I have ever painted one yet. Thou hast not seen me work at it, and canst not know, therefore, from whom the picture originates. Thou hast no skill, my young friend; I ought not to have trusted thee with the affair.”

“I will be honourable,” said Edward, and knocked his fist on the table. “I will be a decent man, so that I may respect myself again, and others may also! Quite different will I be; a new course of life will I begin.”

“Why so angry?” said the old man, and then drank. “I will not prevent thee; it will please me, if I survive it. I have always warned thee and preached to thee; I have tried to accustom thee to occupations; I wished to teach thee to restore pictures, to prepare varnish, to mix colors — in fact, I did not let thee be deficient in anything.”

“Dog of a fellow!” exclaimed Edward, “should I become thy boy, thy mixer of colors? but naturally today I have fallen lower, for I have allowed myself to be employed as a thief by a thief.”

“How the child makes use of injurious expressions,” said the painter, and smiled into his glass. “If I took such a thing to heart, then we should have fighting or bitter enmity on the spot. He means it well, however, in his zeal; the young man has nothing noble in his nature, but as a picture dealer he is of no use.”

Edward laid his head over the table, and the painter wiped away quickly a wine spot so that the young man should not put his sleeve into it.

“The dear, good Salvatore,” said he, then thoughtfully, “is said, too, not to have led the best of lives; they accuse him of being a bandit. When Rembrandt pretended to be dead while living to raise the price of his works, he was not quite true to verity, although he really died some years later, and therefore he had only miscalculated the years of his life.

Thus, when I paint such a picture in the greatest love and humility, I fancy myself one of the old masters, with all their dear peculiarities, very modestly and thoroughly, so that it is always as if the dead man’s mind conducted my hand and brush; and the thing is then finished, and it nods to me its thanks with great heartiness, that I have also finished something of the old virtuoso, who has not been able to accomplish everything, nor yet live forever; and now I fully claim a glass of wine, while I look at it with a more severe examination, and convince myself firmly that it originates really from the old gentleman; and I deliver it thus to another amateur admirer of the dead man, and only request a trifle for the pains that I have let my hand be led.

My own genius has in the meanwhile been suppressed, having worked for the abasement of my own name among artists. Is it, then, such a fearful sin, my friend, when I sacrifice myself in such a child-like manner?”

He lifted up the head of the man lying down, but changed his grinning amiability into a ridiculous seriousness, when he saw the cheeks of the young man covered with tears, which fell uninterruptedly in a warm stream from his eyes.

“Oh, my lost youth!” sobbed Edward. “O ye golden days, ye weeks and years, how sinfully ye have been wasted, as if there lay not in your hours the germ of virtue, of honour, and of fortune; as of this most precious treasure of time was ever to be won again. Like a glass of wasted water have I exhausted my life and the interior of my heart. Oh! what an existence might have opened itself to me, what a fortune to me and to others, if an evil spirit had not dazzled my eyes. Fruitful trees grew around and above, and shaded me entirely, in which the friend, the wife, and the oppressed ones found help, consolation, peace and a country; and I aimed an ax in giddy arrogance at this wood, and must now suffer frost, storms and heat. “

Eulenboch did not know what face to make, still less what he should say, for in this humour, and with such sentiments, he had never seen his young friend before. He was at last only happy and contented that Edward did not observe him, so that in pleasant secrecy he finished his wine.

“So thou wilt be virtuous, my son?” he began at last. “Likewise good, in truth! Few men are so inclined to virtue than I myself, for it requires a quick eye at that, if only to know what virtue is. To be stingy, to extort from people, to lie to oneself and to our Lord is certainly no virtue. But who has the real talent for virtue will find it also. If I procure for a sensible man a good Salvator or Julio Romano, painted by me, and he is pleased with it, then have I always better acted than if I sell a real Raphael to a simpleton, which the simpleton does not know how to value, so that at the bottom of my heart a dressed-up Van der Werft would cause him more joy. My great Julio Romano I must indeed sell personally, for thou hast neither talent nor good luck for such affairs.”

“Those miserable sophisms,” said Edward, “cannot act upon me any longer; the time is over, and thou mayest only take care that they do not catch thee; for with novices it may succeed, but not with connoisseurs like old Walter.”

“Never mind, my child,” said the old painter, “connoisseurs are precisely the best to deceive; and with an inexperienced man I should not like even to try. Oh, this good, old, dear Walter, the sly man! Hast thou not seen the beautiful Hoellenbreughel, which hangs on the third pillar between the sketch of Rubens and the portrait of Van Dyck? It is by me. I came to the little man with the picture: “Will you not buy something pretty?” “What!” exclaimed he, “such caricatures; madness! That is not my affair! show it to me, though.

Well, moreover, I do not take up such nonsense, but as there is a little more gracefulness and drawing in this picture than one otherwise finds in such fantasies, thus I will make an exception of it for once.” In short, he has kept it and shows it to the people, to attest his various taste.”

Edward said, “But wilt thou not yet be a more honest man? It is, however, high time.”

“My young converter,” exclaimed the old man, “I am that long ago. Thou dost not understand the thing, and thou art not at an end with thy dangerous course. Art thou at the limit, and has luckily passed all the cliffs, pillories, lighthouses, then beckon to me boldly, and I will steer, perhaps, after thee. Till then leave me unmolested.”

“Thus, therefore, our course separates,” said Edward, in looking at him in a friendly way. “I have neglected much, but not yet all. I still have some of my property, my house. Here I will settle down simply, and will look for a place as a secretary or a librarian with the Prince, who shortly will arrive here. Perhaps I will travel with him, perhaps that elsewhere fortune — and if not that, I will limit myself here, and seek work and occupation in my native town.”

“And when shall this life of virtue begin?” asked the old man with a grinning laugh.

“Immediately,” said the young man; “tomorrow, today, from this very hour!”

“Foolery,” said the painter, and shook his grey head. “For all good things, one must allow oneself time to prepare, to take a run to finish the old period with a ceremony, and equally so to begin the new one. That was grand custom, that in many quarters our ancestors carried on the carnival to the grave with a truly genuine extravagance, that they at last once more madly halload out and rejoiced in their pleasure, afterwards to be able to be pious, undisturbed, and quite free from any scruples of conscience.

Let us follow the honorable custom. Brother, see, I am so good to thee; give us and thy good humour once more such a regular select banquet, such a lofty farewell and departure feast, so that we, especially I, may think of thee. Let us rejoice with the best wine till late in the night, then thou goest to the right of virtue and moderation, and we others remain to the left where we are.”

“Drunkard!” said Edward, smiling. “If thou only finds a pretext to drink, then all appears right to thee. Let it therefore be on the holy feast of the Twelfth Night.”

“There are four days to that,” sighed the old man, in draining the last remains from his glass, and then he withdrew in silence.

To be continued…

Ludwig Tieck: “Legacy”

Excerpt, translated from the German by G. Greville Moore, 1883.

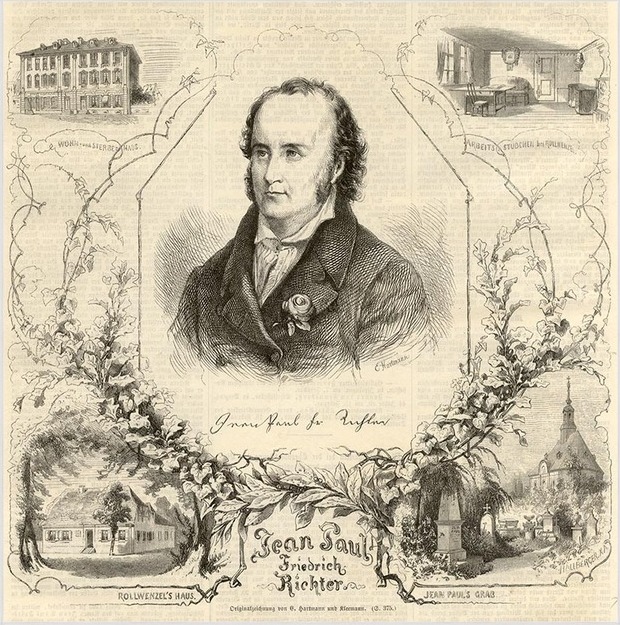

PREFACE: This story was my first attempt at this kind of novel, and the tale arose quite by chance, through the zealous exhortations of a friend. I never was induced to contribute to almanacs or to pocket books, however much Jean Paul, Friedrich Schlegal and other friends have desired me to do so.

Ludwig Tieck, Berlin, 1846

THE LEGACY

“Only step in the meanwhile into the picture gallery,” said the servant , while he let in young Edward; “the old gentleman will come to you immediately.”

With a heavy heart, the young man entered the doorway. “With what other feelings,” thought he, “did I walk through these rooms with my respected father! This is the first time that I come here for such motives, and it shall also be the last. Truly it shall be! and it is time that I think differently of myself and the world.” He walked further in the saloon, while he placed a wrapt-up picture against the wall. “How one can remain thus among lifeless pictures, and exist only with them and for them!” Thus he continued his mute studies. “Is it not as if these enthusiasts perish in a bewitched country? For them, art is only a window through which they look at Nature and the world; they can recognize both only in comparing them with imitations of the same. And thus my father also dreamed away his life; what had not reference to his collection was of no more importance to him that if it had happened beneath the North Pole. Strange how every kind of enthusiasm so easily leads us to limit our existence and all our feelings. “

While he lifted his eyes, he was almost dazzled or frightened at a picture, which hung in the upper region of the high gallery, without the ornament of a frame. A fair girl’s head, with neatly entangled locks and cheerful smile, looked down in a light night-dress, one shoulder somewhat bare, which appeared perfect in form and exquisitely white; in her long, elegant fingers she held a rose, which had just bloomed, and which she approached to her glowing red lips.

“Well, really!” said Edward aloud, “if this picture is by Rubens, as it must be, then the glorious man has excelled all other masters in such subjects! It lives, it breathes! How the fresh rose blooms towards the still fresher lips! how soft and tender the red of both mingles one with the other, though they are so surely divided. And this splendour of the fine shoulders on which the flaxen hair is scattered in disorder! How can old Walter hang his best picture up so high, and without a frame, when all the other trash glitters in the most costly frames. ” He lifted again his head, and began to perceive what a powerful art that of painting is, for the picture became almost more life-like. “No, these eyes!” said he again to himself, quite lost in looking at them; “how could brush and colour produce the like? Does not one see the bosom heave? Do not the fingers and the round arm move?”

And so it was indeed; for in this very moment the charming picture raised itself, and threw with an expression of roguish petulancy the rose downwards, which flew in the young man’s face, then stepped backwards and shut with a clash the small window. Frightened, and ashamed, Edward picked up the rose from the ground. He remembered distinctly the small passage which led above near the gallery to the highest room in the house; the other small windows were covered with pictures, only this one was left as it was, to give light; and the master of the house was accustomed to take a glance at his guests often from there, who wished to visit his picture gallery.

“Is it possible?” said Edward, after he had remembered all of these circumstances, “that little Sophy, within a space of four years, could have grown into such a beauty? “

He pressed unconsciously, and with singular distraction, the rose to his mouth, placed himself against the wall, looking vacantly on the ground, and did not observe that old Walter had been standing near him for some seconds, till Walter, with a friendly tap on the shoulder . woke him out of his reverie.

“Where were you, young man?” said he, jokingly; “you are like one who has seen an apparition.”

“So it seems to me,” said young Edward. “Forgive me for troubling you with my visit.”

“We should not be so strange to one another, young friend,” said the old man heartily. “It is now more than four years that you have not entered my house. Is it right of you so entirely to forget the friend of your father, your former guardian, who was always well disposed toward you, although we had some differences of opinion with one another?”

Edward blushed, and did not know quite what he should answer. “I did not think you would miss me,” he stammered out at last. “Much might have been quite different, but the errors of youth…”

“Let us leave that alone,” said the old man in good humour. What prevents us from renewing our former acquaintanceship and friendship? What brings you now to me? “

Edward looked downward, then cast a very quick and sudden look at his old friend; he lingered still, and then went with a tarrying step to the pillar where the picture stood, which he took out of its covering.

“Look here what I found, unexpectedly, among the legacy of my late father, a picture which was preserved in an old bookcase, which I had not opened in years. Connoisseurs will have it that it is an excellent Salvator Rosa.”

“So it is!” exclaimed old Walter, with an animated look. “Well, that is a glorious discovery!” What good luck that you discovered it so unexpectedly. Yes, my beloved dead friend had treasures in his house, and he did not even know all that he possessed.”

Walter placed the picture in the correct light, examined it with sharp eyes, approached and withdrew again from the picture, followed from a distance the lines of the figures with a connoisseur’s finger, and then said, “Will you let me have it? Name a price and the picture is mine, if it is not too dear.”

In the meanwhile, a stranger had approached, who in another direction of the room copied a Julio Romano.

“A Salvator?” asked he, in a somewhat abrupt tone of voice, “you have really found an old possession in a legacy?”

“To be sure,” said Edward, eyeing the stranger with a proud look, whose smooth great coat and simple bearing led him to suppose he was a traveling artist.

“Then you are yourself deceived,” replied the stranger, in a proud, rough voice, “if you do not wish to deceive others; for this picture is apparently rather a modern one, perhaps quite a new one — at least not more than ten years old — an imitation of the manner of the master good enough to deceive for an instant, but after a nearer examination shows its defects to the connoisseur .”

“I am greatly surprised at this presumption,” exclaimed Edward, quite beside himself, “in the legacy of my father there was nothing but good pictures, and originals, for Mr. Walter and he were always reckoned the best connoisseurs in the town. And what do you want more? At our celebrated dealer’s, Erich, hangs the pendant to this Salvator, for which a few days ago a traveler had offered a very large sum. If you put both together you will see that they are both by the same master and belong together.”

“Indeed?” said the stranger, in a long drawling tone. “You know all about that Salvator also? Naturally it is painted by the same hand like this one here; that there can be no doubt. In this town, the originals of this master are rare, and Walter and Mr. Erich possessed none of him; but I am well acquainted with the brush of this great master, and give you my word that he never touched these pictures, but that they proceed from a later man, an amateur who wishes to deceive with them.”

“Your word!” exclaimed Edward, blushing deeply; “Your word! I should think my word here is as good, and perhaps, better than yours.”

“Certainly not,” said the stranger; “and besides I must regret that you allow yourself to be overcome and betrayed by your hot temper. You know, then, about the fabrication of this work, and know the clever copier?”

“No!” exclaimed Edward, more violently; “you shall prove to me this insult, sir. These assertions and untruths that you so boldly utter announce more than a hateful disposition.”

The magistrate, Walter, was in greatest embarrassment that this scene should take place in his house. He stood searchingly before the picture, and had already convinced himself that it was a modern one, but an excellent imitation of the celebrated master’s, which could also deceive an experienced eye. It pained him inwardly that young Edward was involved in this bad affair. The two disputants were so furiously enraged that all mediation was impossible.”

“What you say now, sir!” exclaimed the stranger, also in a raised tone of voice, “you are really beneath my anger, and I am rejoiced that a mere chance has led me into this gallery, which has prevented a worthy picture-collector from being deceived.”

Edward foamed with rage.

“Thus it was not intended,” said the old man, kindly.

“That this was the intention assuredly,” continued the stranger. “It is an old, oft-repeated game, and with a person to whom one has not even found worth the while to apply a new scheme. I saw at the picture-dealer’s that so-called Salvator Rosa; the possessor took it for a real one, and was the more confirmed therein because a traveler, who, judging by his clothes, might have been a gentleman, offered a high price for it. On his return, he said he would have the picture, and asked the dealer not to part with it for at least four weeks. And who was this gentleman? The discharged servant of Count Alten of Vienna. Thus it is clear that this game , from whom it may proceed, was plotted against you, Mr. Walter, and your friend, Erich.”

Edward had in the meanwhile again wrapt up with trembling hands his picture. He gnashed his teeth, stamped his feet, and exclaimed: “The devil shall pay me this trick!” He rushed out the door and did not observe that the girl looked again from above down on the gallery. She was attracted by the noise of the men quarreling.

“My worthy sir,” said the old man, turning toward the stranger; “you have done me harm. You have dealt too harshly with the young man. He is frivolous and extravagant in his manners, but I have not as yet heard of any wicked action done by him.”

“There must always be a commencement,” said the stranger, with great bitterness. “Today, he has at least paid his apprentice fee, and either turns back or learns so much that they may begin his business again more knowingly, and in respect lose self-possession.”

“He is for certain deceived himself,” said old Walter, “or he has found the picture as he says; and his father, who was a great connoisseur, has put it aside on that account, because it was not a real one.”

“You wish to turn it the best way you can, sir,” said the stranger, “but in this case, the young man would not have been so unnecessarily hasty. Who is he then, really?”

“His father,” related the old man, “was a rich man, who left great possessions behind him; and had so great a passion for his art as certainly very few men are capable of having. On this, he spent a great deal of his means, and his collection was incomparable. On account of this, he neglected a little too much the education of his only son; so when, therefore, the old man died, the young man only thought of spending money and associated with spongers and bad people, and keeping women and horses. When he became of age, there were enormous debts to be paid to usurers and in bills of exchange, but he placed all his vanity in squandering more; the works of art were sold, for he had no taste for them; I took them for a small sum. Now he has, perhaps with the exception of the beautiful house, run through almost everything, and this too must be mortgaged. He has scarcely acquired any knowledge, an occupation is insupportable to him, and so one must see with pity how he goes to his ruin.”

“The daily history of so many,” remarked the stranger, “and the usual way of unworthy vanity which conducts men joyfully into the arms of contempt.”

“How have you acquired your keen eye of judgment?” asked the magistrate. “I am also astonished at the manner in which you copy the Julio, for you are not a professional artist, you say.”

“But I have studied the art for a long time, I visited the most important galleries in Europe repeatedly, and not without profit. My eye is naturally sharp and true, and improved also by practice and made sure, so that I can flatter myself not so easily to be led astray, least of all with my favorites.” The stranger then bid good-bye, after he had been made to promise to the picture collector that he would dine with him at mid-day on the following day, for the old man had acquired great respect for the traveler on account of his knowledge.

To be continued…

Salvatore Rosa: Astraias parting from the Hirten (mid-17th Century)

Heinrich Heine on Ludwig Tieck Pt. II

Oh, the sighs and lamentations one

May hear on every side,

Throughout the whole of Nature,

If one but only give them ear.

Ludwig Tieck

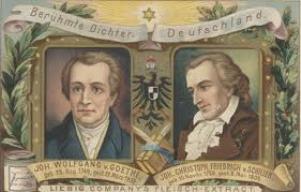

“But now a strange change takes place in Tieck, which is shown in his third manner. Having been silent for a long time after the fall of the Schlegals, he again appeared in public and that in a manner which was little expected of him. The former enthusiast, who had once thrown himself on the breast of the Roman Catholic Church, who had fought Enlightenment and Protestantism with such power, who breathed nothing but feudality and the Middle Age, and who only loved art in naive outpourings of the heart, now appeared as the foe of what was visionary, as a depictor of modern middle-class life, as an artist who required in art the clearest self-consciousness – in short, as a reasonable man.

Thus, has he shown himself in a series of recent novels, some of which are known in France. A deep study of Goethe is visible in them, and it is specially this Goetheism which characterizes his third style. There is the same artistic clearness, cheerfulness, repose and irony. As the school of the Schlegals did not succeed in drawing Goethe into it, now we see how it, represented by Tieck, went over to him.

Tieck was born in Berlin, the 31st of May 1773. For many years, he has lived in Dresden, where he is chiefly busied with the theatre, and he who in his earlier writings always ridiculed the court-councilor as a type of the ridiculous, has himself been made such a Royal Saxon dignitary. God is sometimes a greater satirist that Tieck.

And now a strange misunderstanding has come between the reason and the imagination of this author. The former, or the reason of Tieck, is an honest, sober, plain citizen, who worships practical economy and abhors the visionary. The other, that is, the Tieck imagination, is still, as of yore, the chevelresque lady with the flowing feather on her cap, the falcon on her fist. The pair lead a curious wedded life, and it is often sad to see how the poor dame of high nobility must help the sober citizen spouse in his household or in his cheese-shop. But often in the night, when the good man, with his cotton night cap on, snores peacefully, the noble lady rises from the matrimonial bed of durance vile, and mounts her white horse, and hunts away as merrily as of yore in the enchanted forest of romance.

But I cannot refrain from remarking that of late the Tieckian reason in romance has become sterner than before, and that at the same time his imagination pays penance more and more for her romance nature, so that when the nights are cold she lies comfortably yawning in the marriage bed, and hugs up to her meager husband almost lovingly.

And yet Tieck is always a good poet, for he can create living forms, and words burst from his heart which move our own. But a faint-heartedness, something undecided and uncertain, or a certain feeble-mindedness is, or ever was, to be observed in him. The want of decision is only too perceptible in all that he did or wrote. Certainly, there is no independent character in his works. His first manner shows him as a mere nothing, his second as a true and trusty squire of the Schlegals, and his third as an imitator of Goethe. His theatrical criticisms, which he published under the title of “Dramaturgic Pages,” constitute his most original work; but they are theatrical criticisms.

In order to represent Hamlet as an altogether weak-minded man, Shakespeare makes him, in his conversation with the comedians, appear as an admirable theatrical critic.

Tieck never troubled himself with serious studies; his work of this kind was limited to modern languages and the older documents of German poetry. As a true Romanticist, he was always a stranger to classic studies; nor did he ever busy himself with philosophy, which seems to have been altogether repugnant to him. From the fields of philosophy, Tieck gathered only flowers and switches – the first for the noses of his friends, and the latter for the backs of his foes. With serious culture or scientific writings, he had naught to do. His writings are bouquets and bundles of rods, but never a sheath with an ear of corn.

Next to Goethe, Tieck often imitated Cervantes. The humoristic irony, or, as I may say, the ironic humour, of these two modern poets spreads its perfume in the novels written in Tieck’s third style. Irony and humour are therein so blended as to seem but one. There is much said now among us as to this humorous irony; the men of the Goethean school of art praise it as a special glory of their master, and it plays a great part in German literature. But it is only a sign of political servitude, and as Cervantes in the days of the Inquisition took refuge in humorous irony to set forth his thoughts without giving a chance to catch hold to the familiars of the Holy Office, so Goethe expressed with it that which he, as Minister of State and a courtier, could not directly utter. Goethe never suppressed truth, but where he could not show her naked, he clad her lightly in humour and irony.

The honest Germans, who pine under censorship and spiritual oppression of every kind, and yet never can suppress what the heart inspires, have specially taken to the ironic and humorous form. It was the only means of exit which was left to their nobler feelings, and in this form German honourableness is most touchingly shown.

This again reminds me of the marvelous prince of Denmark. Hamlet is the most honourable fellow who ever wore a skin. His dissimulation only serves as an offset to what oppresses from without; he is peculiar and odd because such conduct is less offensive to court etiquette than open breach of it. But in all his humourous ironical jests he lets it be distinctly perceived that he is acting; in all he does and say his real meaning is visible for all who can see, even to the king, to whom he cannot speak the plain truth (for that he is too weak), and yet from whom he will by no means hide it. Hamlet is through and through honourable; only the most honourable man could say, “We are arrant knaves all;” and while he plays the lunatic he will not deceive us, and in his heart conscious that he is really mad.

I have still to praise two works by Tieck, for which he specially deserved commendation of the German public. One of these is a translation of a series of English dramatists anterior to Shakespeare, and his version of “Don Quixote.” Among the former are several which bear the same names and treat of the same subjects as the Shakespeare plays. We find in them the same intrigues and scenic development; in a word, all of the Shakespearean tragedy except the poetry.

Some commentators have expressed it as their opinion that these are the first sketches of the great poet, as it were the dramatic cartoons, and if I err not, Tieck himself has declared that “King John,” one of these old plays, is a work by Shakespeare, or, so to speak, a prelude to the great masterpiece known to us by this name. But this is an error. These tragedies are nothing more than old plays on hand, which Shakespeare, as we know, worked over again, partly or wholly, as they were required by the managers, who paid him for such work twelve to sixteen shillings each. And so a poor hack of an adapter of other men’s plays outweighs the proudest literary kings of our time.

The other great poet, Miguel de Cervantes, played as modest a part in the real world. These two men, the composer of “Hamlet” and the composer of “Don Quixote,” are the greatest poets of modern times.

The translation of “Don Quixote” is a special success. No one has so exquisitely hit off the insane dignity of the ingenious hidalgo of La Manche, and set it forth so accurately, as our admirable Tieck. The books reads almost like a German original, and forms next after “Hamlet” and “Faust,” the favourite reading of Germans. The cause of this is, that in these two astonishing and profound works we have found, as in “Don Quixote,” the tragedy of our own nothingness.

German youth love “Hamlet” because they feel with him “time is out of joint.” They sigh in the same way to think that they are called upon to set it right, feel also their incredible weakness and declaim. “To be or not to be.”

Men of mature age, however, prefer “Faust.” Their mental condition attracts them to the bold investigator who makes a compact with the invisible world and who fears not the devil.

But those who have seen that all is vain, and that all human efforts are useless, prefer the romance of Cervantes, for they see all inspiration satirised in it, and all of our knights of the present who fight and suffer for ideas appear to them as so many Don Quixotes.

Did Miguel de Cervantes suspect what application a later age would make of his work? Did he really parody idealist inspiration in his tall lean knight, and common sense in his fat squire? Anyhow, the latter is always the most ridiculous, for plain common sense, with all its trite and every day proverbs, must all the same trot along after Inspiration on its easy-paced donkey; in despite of his clearer insight, he and his ass must suffer all discomfort, such as befalls the Knight himself — yea, the ideal inspiration is of such powerfully attractive nature, that common sense with the donkey must follow whether he will or not.

Or did this man of deep and subtle wit mean to mock mankind still more shrewdly? Did he allogorise the soul in the form of Don Quixote and the body in the form of Sancho Panza? And is the whole poem a great mystery, in which the question of spirit and matter is discussed with terrible truthfulness? This much I see in the book, that the poor material Sancho must suffer much for the spiritual Don Quixote, and that he gets for the noble views of his master the most ignoble stripes, and that he is always more sensible than his high-trotting master, for he knows that lashes and cuffs have evil taste, but the little sausage in the olla padrida is a very good one. Indeed, the body often seems to have more insight than the soul, and man thinks frequently far better with his back and belly than with his head.

But if old Cervantes only meant to depict in “Don Quixote” the fools who wished to restore medieval chivalry and call again to life a perished past, it is a merry irony of chance that it was just the Romantic School itself which gave us the best translation of a book in which its own folly is most delightfully satirised.”

Heinrich Heine on Ludwig Tieck, Pt. I

Their words have been honored by such Lieder composers as Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn and Brahms. For more information on the music inspired by Heine and Tieck, as well as other fine German poets, I invite you to visit Emily Ezust’s Lied & Art Song Texts Page. To better appreciate the challenges of their time and circumstance, please see previous post, “Young Germany and Heinrich Heine.”

“You could scarcely fail,” replied the stranger.

“Whoever knows how to seek,

Whoever feels his heart drawn toward it with a

Right inward longing

Will find friends of former ages there,

And glorious things, and all that he wishes most.”

Ludwig Tieck

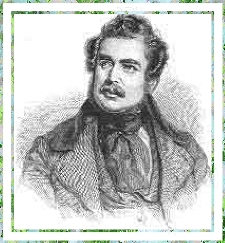

“After the Schlegals, Ludwig Tieck was the most effective author of THE ROMANTIC SCHOOL. For it, he fought, thought and sang. He was a poet, a name which neither of the Schlegals deserved; for he was a true son of Phoebus Apollo, and, like his ever-youthful father, he bore not only the lyre but the bow, with a quiver full of rattling, ringing arrows. He was, like the Delphian god, intoxicated with lyrical fire and critical cruelty. And when, like him to, when he had pitilessly flayed alive some literary Marsyas he merrily grasped with bloody fingers the golden chords of his lyre and sang a sweet song of love.

The poetical polemic which Tieck waged in dramatic form against the adversaries of the school belongs to the most remarkable curiosities of our literature. They are satirical plays, which are generally compared with the comedies of Aristophanes. Yet they differ from the latter almost as much as a tragedy by Sophocles differs from Shakespeare. If the ancient comedies had the same cut and style, the strictly drilled step, and the exquisitely metrical language of ancient tragedies, so that they might pass for parodies, so are the dramatic satires of Tieck cut in as original and strange a manner; just as Anglicanly irregular and as metrically capricious as the tragedies of Shakespeare.

Was this form invented by Tieck? No; for it existed already among the people of Italy. He who understands Italian might get a tolerably correct idea of the dramas of Tieck if he will dream himself into the chequered-bizarre, Venetian-fantastic fairy tale comedies of Gozzi, mixed with a little German moonshine. In fact, Tieck took many of his masks from this merry child of the Lagunes. Following his example, many German poets have mastered the same form; hence, we have had comedies whose comic effects were not produced by a single fanciful character or a gay intrigue, but where we are transported at once into a wild and merry world, where animals talk and act like men, and where chance and caprice take its place in the natural order of things.

This we also find in Aristophanes. But the latter chose this form to reveal to us his profoundest views of the world, as , for instance, in the “Birds” where the maddest efforts of mankind, their desire to build the grandest castles in the air, their defiance of the eternal gods, and the vain joy of their triumphs, are set forth in the most ludicrous caricatures.

And it was that which made Aristophanes so great, because his views of the world were so great, because they were grander and more tragic than the tragedian himself; because his comedies were really jesting tragedies. Take, for example, his Paisteteros, who is not shown up in his ridiculous worthlessness at the end of the play, as a modern poet would have planned it. On the contrary, he woos and wins the beautiful, marvellously mighty Basilea; he sores with this heavenly bride to his city in the air; the gods are compelled to obey him, folly celebrates its marriage with power, and the play ends with joyous marriage-hymns.

Can there be, for any reasonable man, anything more cruelly tragic than this victory and triumph of folly? Our German Aristophanes do not rise so high; they refrain from such lofty views of life; they manifest the utmost modesty as regards discussing those very important relations of man, politics and religion; they only venture on the theme which Aristophanes himself has treated in the “Frogs” as a subject of satire – the stage itself – and they have mocked with more or less cleverness its failings.

Still we must consider the politically enslaved condition of Germany. Our wits, restrained from ridiculing real princes, made up for it by attacking kings of the theatre and queens of the coulisses. We, who were almost destitute of political journals which discussed public affairs, were all the more blessed with countless aesthetic journals, containing nothing but idle tales and theatrical criticisms, so that anyone who saw our newspapers might well suppose that the whole German race consisted of chattering nursery maids and theatrical critics.

And yet it would have been unjust.

How little content we were with such miserable scribbling appeared immediately after the Revolution of July, when it seemed as if free and bold words might be uttered in our own dear native land. There sprung up all at once newspapers which criticized the good and bad acting of real kings, and many of them who had forgotten their parts were hissed in their own capitals.

Our literary Scheherazades, who had hitherto put the public, that plump Sultan, to sleep with their little tales, were now silent; the actors saw with amazement the pit empty, however divinely they played, and even the reserved seats of the terrible town-critics were often vacant. Once the good heroes of boards always complained that they were continually subjects of public conversation, and that even their domestic affairs were discussed in the journals. But what was their horror when the awful truth flashed upon them that nobody now cared what they did!

In fact, when the Revolution broke out in Germany, there was an end to theatres and and dramatic criticism, and the terrified feuilletonists, actors and critics apprehended – and justly – that “Art was going to the dogs.” But this great calamity was fortunately averted from our native land by the wisdom and power of the Frankfort Diet.

There will be, let us hope, no revolution in Germany. We are protected from the guillotine and all the terrors of freedom of the press . Even the Chamber of Deputies, whose competition so greatly injured the regularly licensed theatres, is done away with; and art is saved! Just now they are doing all they can for art, especially in Prussia. The museums gleam with all the splendours of color, the orchestras sound, the ballet-girls leap their loveliest and liveliest entrechats, and a thousand and one novels enrapture the public, and theatrical criticism blooms again.

Justinus relates in his “Histories” that when Cyrus had quieted the revolt of the Lydians , he succeeded in taming stubborn, liberty-loving spirit by inducing in them an interest in the fine arts and other pleasant things. So there was nothing more heard of Lydian liberty or rebellion, but all the more famously did the Lydian restaurant-keepers, panders and artists flourish.

Now there is in Germany rest and repose. Theatrical criticism and novels are to the fore, and as Tieck exceeds in both, all friends of art pay him the tribute due. He is, in fact, the best novelist in Germany. Yet all his works are not of equal worth or of the same kind. We can distinguish in him, as in painters, many manners.

His first was altogether that of the old school. Then he wrote to order, and by command of a bookseller, who was no other than the Nicolai himself,the most self-willed of champions of enlightenment and humanity, the greatest enemy of superstition, mysticism and romance. Nicolai was an indifferent writer, a prosaic old wig, who often made himself ridiculous by scenting Jesuitism. But we, the later born, must admit that old Nicolai was a throughly honest man, who meant well for the German race, and who in the holy cause of liberty did not dread that cruelest of all martyrdoms, ridicule. I was told in Berlin that Tieck once lived in Nicolai’s house, one story above the latter, and so the modern time walked over the head of the old.

The works which Tieck wrote in his first style, mostly tales and long novels, among which “William Lovell” is the best, are very insignificant and without poetry. It would seem as if the rich poetic nature of this man was frugal and stinted in his youth, and that he saved up all his spiritual wealth for a later time. Or was Tieck himself ignorant of the treasure which was in him, and were the Schlegals needed to discover it with their divining rod? For as soon as he came in touch with them, all the riches of his imagination, his deep feeling and his wit. at once showed themselves. Diamonds gleamed, the purest pearls rolled out in streams, and over all flashed the ruby, the fabulous carbuncle gem of which romantic poets have often said and sung. This rich breast was the real treasury whence the Schlegals drew the funds for their literary campaigns. Tieck had to write for the school the satirical which I have mentioned, and prepare according to the new aesthetic recipes many poems of every kind. This is his second style.

His best productions in it are “The Emperor Octavian,” “The Holy Genofeva,” and “Fortunatus,” three dramas which take their names from chapbooks. The poet has given to these old tales, which have ever been dear to the German world, new and costly clothing. Honestly speaking, I prefer them in their old naive, true-hearted form. Beautiful as Tieck’s “Genofeva” may be, I love far better the old Volkbuch, very badly printed at Cologne on the Rhine, with its rude woodcuts, in which it is touching to see the poor naked Countess Palatine, with only her long hair for chaste clothing, while her little Schmerzenreich is nursed at the teats of a pitying doe.

Far more precious than these novels are the novels which Tieck wrote in this, his second manner. These too are mostly taken from the old popular legends. The best are “The Blond Eckbert” and “The Runenberg.” In these compositions, we feel a mysterious depth of meaning, a marvelous union with Nature, especially with the realm of plants and stones. The reader seems to be in an enchanted forest; he sees subterranean springs and streams rustling melodiously, and his own name whispered by the trees. Broad-leaved clinging plants wind vexingly about his feet, wild and strange wonder- flowers look at him with varicoloured longing eyes, invisible lips kiss his cheeks with mocking tenderness, tall mushrooms like golden bells grow singing about the root, great silent birds cradle themselves on the boughs, and nod adown with their cunning long bills.

All breathes – lurks – is thrilling with expectation, when suddenly the soft tune of a hunter’s horn is heard, and a beautiful lady with waving plumes on her cap, a falcon on her wrist, rides past on a white palfrey. And this fair dame is as bright and blond and violet-eyed, as smiling and yet serene, as true and yet as ironic, as chaste and yet as passionate, as the imagination of our glorious Ludwig Tieck. Yes! his fantasy is a wondrous winsome damoiselle of high degree, who in an enchanted forest hunts fabulous creatures – perhaps the rare unicorn which can be caught only by a pure maid.”

To be continued tomorrow in Part II.

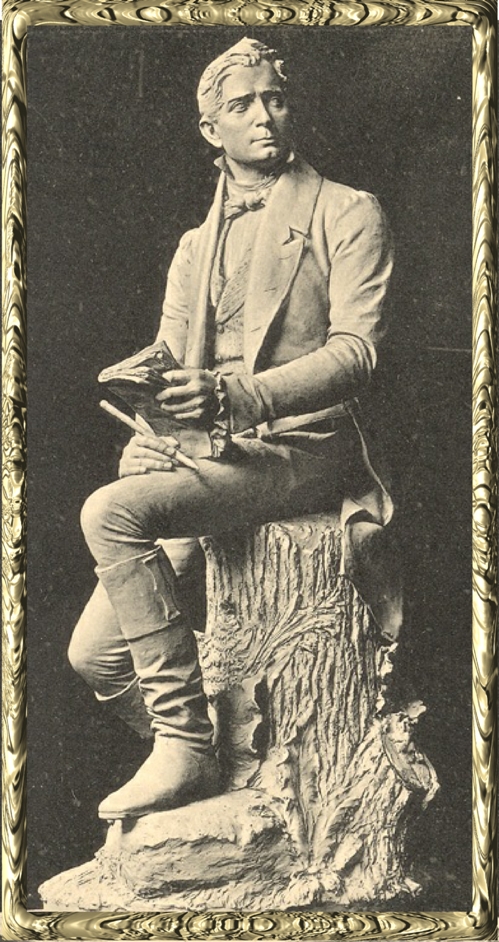

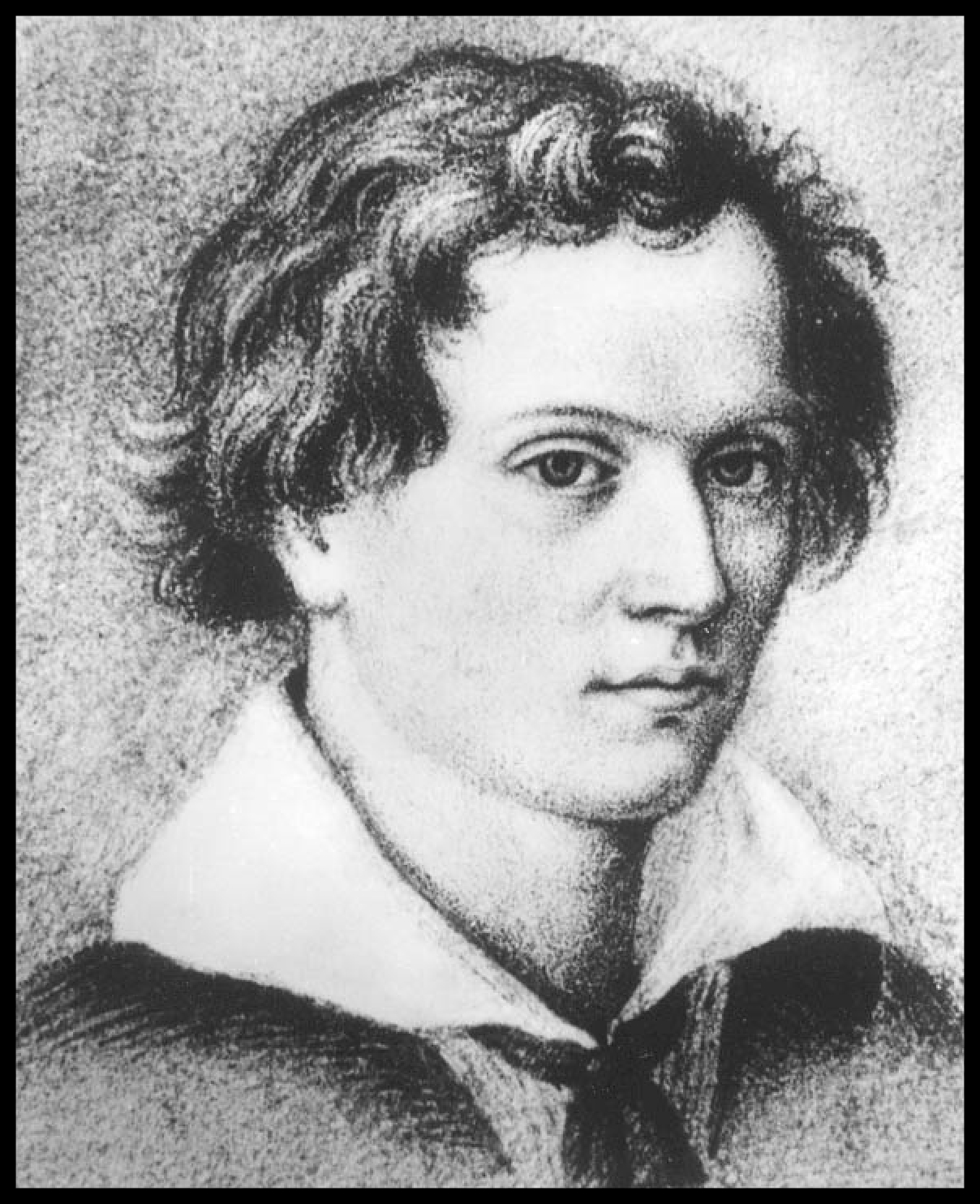

Johann Ludwig Tieck

Young Germany and Heinrich Heine

Who wrote:

But lords of the realm of dreams are we …

I quote William Langer in preparation for my next post: Heinrich Heine’s 1833-1836 “The Romantic School” … Ludwig Tieck.

Heine was exiled from his German home land in 1835.

“The extent to which the repression of thought could go was best shown by the fate of the Young German movement, a strictly literary movement which bore no relation to the Mazzinian organization of the same name. The Young Germans were a group of prose writers who had in common their reaction against classicism, idealism and romanticism, and their devotion to the attitude and thought of the Enlightenment. Greatly concerned with questions of the day, they aimed to reach a greater public through effective journalistic writing.

These writers reflected the ideas of French democracy in their demands not only in politics but also in social relations.

The group was greatly influenced by two expatriate writers, Ludwig Börne and Heinrich Heine. Börne, sometimes described as the father of German political journalism, was a thoroughgoing democrat, an admirer of Robespierre as the incarnation of republican virtue. He had hurried to Paris on the eve of the July Revolution, and during the years 1831-1833 sent to Germany 112 Letters from Paris in which he described French conditions in glowing terms and compared the fighting French democrats with the humble and subservient Germans.

Heine, one of the greatest of German writers and a satirist sans pareil, arrived in Paris in 1831 and in 1832 published his reports under the title French Conditions, in which, again, he rhapsodized about the land of liberty and laughed heartily over his benighted and submissive countrymen. “In France,” he declared, “even one-tenth of the sufferings borne by the Germans would have provoked thirty-six revolutions and caused thirty-six princes to lose their heads as well as their thrones.” *

*Langer, William, “The Rise of Modern Europe: Political and Social Upheaval: 1832-1852.” 1969, pp. 123,573.

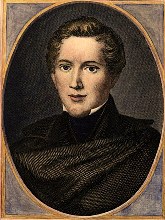

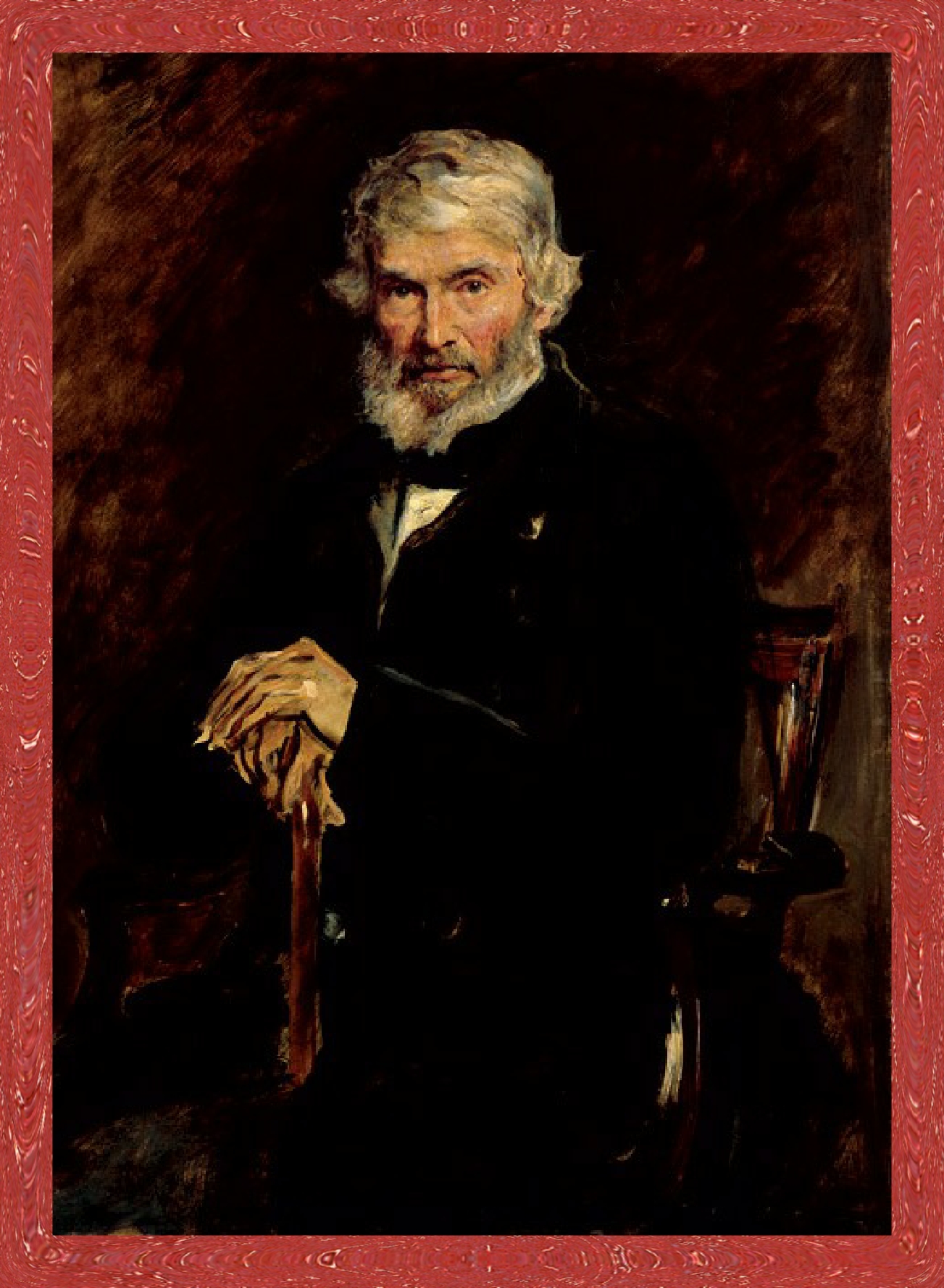

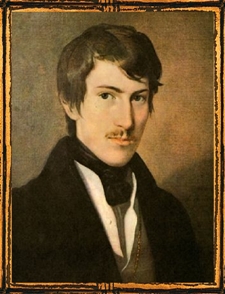

Heinrich Heine

← Previous page