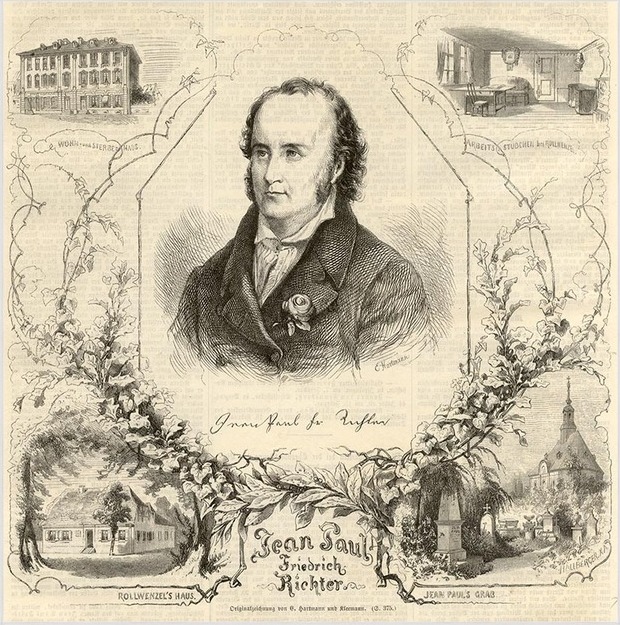

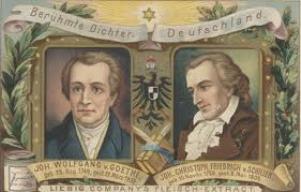

Madame de Staël: Goethe’s Egmont 2/2

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. III, 153-162.

Child! Child! Forbear!

As if goaded by invisible spirits,

The sun steeds of time bear onward

The light car of our destiny

And nothing remains for us

But, with calm self-possession,

Firmly, to grasp the reins, and

Now right, now left,

To steer the wheels here from the precipice

And there from the rock.

Whether he is hasting, who knows?

Does anyone consider whence he came?

A citizen of Brussels: “God forbid that we should listen to you any longer! Some misfortune would be the consequence of it.”

Clara: “Stay, stay! Do not leave me because I speak of him whom with so much ardour you press’d forward to meet when public report announced his arrival; when each of you exclaimed, Egmont comes! He comes! Then, the inhabitants of the streets through which he was to pass, esteemed themselves happy; as soon as the footstep of his horse was heard, each abandoned his labour to run out to meet him, and the beam which shot from his eye, coloured your dejected countenances with hope and joy.

Some among you carried their children to the threshold of the door, and raising them in their arms, cried out, ‘Behold, this is the great Egmont, it is! He, who will procure for you times far happier than those which your poor fathers have endured.’ Your children will demand of you, what is become of the times which you then promised them? What! We lose our moments in vain words! You are inactive, you betray him!”

Brackenbourg, the friend of Caral, conjures her to go home. “What will your mother say?” cries he.

Clara: “Thinkest thou that I am a child, or bereft of my senses? No, they must listen to me: Hear me, fellow citizens! I see that you are perplexed, and that you can scarcely recollect yourselves amidst the dangers which threaten you. Suffer me to draw your attention to the past – alas! even to the past of yesterday. Think on the future; can you live? Will they suffer you to live, if he perishes? With him the last breath of your liberty will be extinguished. Was he not everything to you? For whom, then did he expose himself to dangers without number? His wounds — he received them for you; that great soul, wholly devoted to your service, now wastes its energies in a dungeon.

Murder spreads its snares around him; he thinks of you, perhaps he still hopes in you. For the first time he stands in need of your assistance. He, who to this very day, has been employed only in heaping on you his services and his benefactions.”

A Citizen of Brussels (to Brackenbourg): “Send her away, she afflicts us.”

Clara: “How, then! I have no strength, no arms skillful in battle as yours are; but I have what you want, courage and contempt of danger! Why cannot I infuse my soul into yours? I will go forth in the midst of you: A defenseless standard has often rallied a noble army. My spirit shall be like a flame preceding your steps; enthusiasm and love shall at length re-unite this dispersed and wavering people.”

Brackenbourg informs Clara that they perceive not far from them some Spanish soldiers who may possibly listen to them. “My friend,” said he, “consider in what place we are.”

Clara: “In what place! Under that heaven whose magnificent vault seems to bow with complacency on the head of Egmont when he appeared. Conduct me to his prison, you know the road to the old castle. Guide my steps, I will follow you.”

Brackenbourg draws Clara to her own habitation, and goes out again to enquire the fate of the Count of Egmont. He returns, and Clara, whose last resolution is already taken, insists on his relating to her all that he has heard.

“Is he condemned?” (she exclaims.)

Brackenbourg: “He is, I cannot doubt of it.”

Clara: “Does he still live?”

Brackenbourg: “Yes.”

Clara: “And how can you assure me of it? Tyranny destroys the generous man during the darkness of the night, and hides his blood from every eye — the people, oppressed and overwhelmed, sleep and dream that they will rescue him, and during that time his indignant spirit has already quitted this world. He is no more! Do not deceive me, he is no more!”

Brackenbourg: “No, I repeat it, alas! He still lives, because the Spaniards destined for the people they mean to oppress, a terrifying spectacle; a sight which must break every heart in which the spirit of liberty still resides.”

Clara: “You may speak out: I also will tranquilly listen to the sentence of my death. I already approach the region of the blessed. Already consolation reaches me from that abode of peace. Speak.”

Brackenbourg: “The reports which circulate, and the doubled guard, made me suspect that something formidable was prepared this night on the public square. By various windings I got to a house, whose windows front that way; the wind agitated the flambeaux, which was borne in the hands of a numerous circle of Spanish soldiers; and as I endeavored to look through that uncertain light, I shuddered on perceiving a high scaffold; several people were occupied in covering the floor with black cloth, and the steps of the staircase were already invested with that funereal garb.

One might have supposed they were celebrating the consecration of some horrible sacrifice. A white crucifix, which during the night shone like silver, was placed on one side of the scaffold. The terrible certainty was there, before my eyes; but the flambeaux by degrees were extinguished, every object soon disappeared, and the criminal work of darkness retired again into the bosom of night.”

The son of the Duke of Alva discovers that he has been made the instrument of Egmont’s destruction, and he determines, at all hazards, to save him; Egmont demands of him only one service, which is to protect Clara when he shall be no more. But we learn that, resolved not to survive the man she loves, she has destroyed herself. Egmont is executed; and the bitter resentment which Ferdinand feels against his father is the punishment of the Duke of Alva, who, it is said, never loved anything on earth except his son.

It seems to me that with a few variations, it would be possible to adapt this play to the French model. I have passed over in silence some scenes which could not be introduced on our theatre. In the first place, that with which the tragedy begins: some of Egmont’s soldiers, and some citizens of Brussels, are conversing together on the subject of his exploits. In a dialogue, very lively and natural, they relate the principal actions of his life, and in their language and narratives, shew the high confidence with which he had inspired them.

‘Tis thus that Shakespeare prepares the entrance of Julius Caesar; and the Camp of Wallenstein is compared with the same intention. But in France, we should not endure a mixture of the language of the people with that of tragic dignity; and this frequently gives monotony to our second-rate tragedies. Pompous expressions, and heroic situations, are necessarily few in number. And besides, tender emotions rarely penetrate to the bottom of the soul when the imagination is not previously captivated by those simple but true details which give life to the smallest circumstances.

The family to which Clara belongs is represented as completely that of a citizen; her mother is extremely vulgar. He who is to marry her, is indeed passionately attached to her, but one does not like to consider Egmont as the rival of such an inferior man; it is true that everything which surrounds Clara serves to set off the purity of her soul, but nevertheless in France we should not allow in the dramatic of first principles in that of painting, the shade which renders the light more striking.

As we see both of these at once in a picture, we receive, at the same time, the effect of both. It is not the same in a theatrical performance where the action follows in succession; the scene which hurts our feelings is not tolerated in consideration of the advantageous light it is to throw on the following scene; and we expect that the contrast shall consist in beauties, different indeed, but which shall nevertheless be beauties.

The conclusion of Goethe’s tragedy does not harmonize with the former part; the Count of Egmont falls asleep a few minutes before he ascends the scaffold. Clara, who is dead, appears to be him during his sleep, surrounded by celestial brilliance, and informs him that the cause of liberty, which he had served so well, will one day triumph. This wonderful denouement cannot accord with an historical performance.

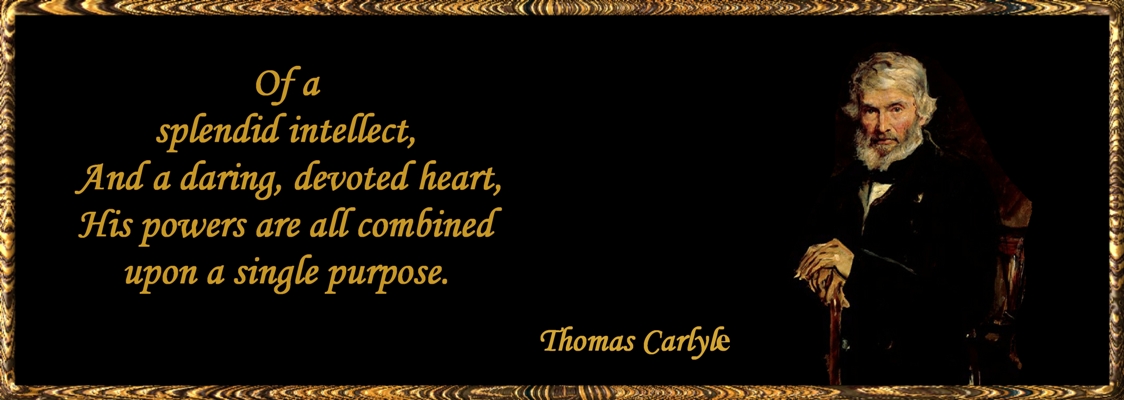

The Germans are, in general, embarrassed about the conclusion of their pieces; and the Chinese proverb is particularly applicable to them, which says, “When we have ten steps to take, the ninth brings us half way.” The talent necessary to finish a composition of any kind demands a sort of cleverness, and of calculation, which agrees but badly with the vague and indefinite imagination displayed by the Germans in all their works.

Besides, it requires art, and a great deal of art, to find a proper denouement, for there are seldom any in real life: Facts are linked one to the other, and their consequences are lost in the lapse of time. The knowledge of the theatre alone teaches us to circumscribe the principal event, and make all the accessory ones concur to the same purpose. But to combine effects seems to the Germans almost like hypocrisy, and the spirit of calculation appears to them irreconcilable with inspiration.

Of all the writers, however, Goethe is certainly best able to unite the frailties of genius with its bolder flights; but he does not vouchsafe to give himself the trouble of arranging dramatic situations so as to render them properly theatrical. If they are fine in themselves, he cares for nothing else.

His German audience at Weimar ask no better than to wait the development of his plans, and to guess at his intention — as patient, as intelligent, as the ancient Greek chorus, they do not expect merely to be amused as sovereigns commonly do, whether they are people or kings, they contribute to their own pleasure, by analyzing and explaining what did not at first strike them — such a public is truly like an artist in its judgments.

I stand high, but I can and must rise yet higher.

Courage, strength and hope possess my soul.

Not yet, have I attained the height of my ambition;

That once achieved, I will stand firmly and without fear.

Should I fall, should a thunderclap, a storm blast,

Ay, a false step of my own,

Precipitate me into the abyss,

So be it.

I shall lie there with thousands of others.

I have never distained, even for a trifling stake,

To throw the bloody die with my gallant comrades,

And shall I hesitate now,

When all that is most precious in life

Is set upon the cast?

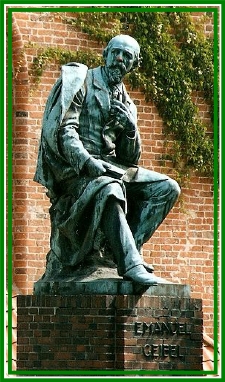

Egmont and Hoorn

.