Category Archives: Goethe

Goethe: “The Fisherman”

Fisherman and the Siren by Lord Frederic Leighton

THE FISHERMAN

1778

The waters rush'd, the waters rose,

A fisherman sat by,

While on his line in calm repose

He cast his patient eye.

And as he sat, and hearken'd there,

The flood was cleft in twain,

And, lo! a dripping mermaid fair

Sprang from the troubled main.

She sang to him, and spake the while

"Why lurest thou my brood,

With human wit and human guile

From out their native flood?

Oh, couldst thou know how gladly dart

The fish across the sea,

Thou wouldst descend, e'en as thou art,

And truly happy be!

Do not the sun and moon with grace

Their forms in ocean lave?

Shines not with twofold charms their face,

When rising from the wave?

The deep, deep heavens, then lure thee not,--

The moist yet radiant blue,--

Not thine own form,--to tempt thy lot

'Midst this eternal dew?"

The waters rush'd, the waters rose,

Wetting his naked feet;

As if his true love's words were those,

His heart with longing beat.

She sang to him, to him spake she,

His doom was fix'd, I ween;

Half drew she him, and half sank he,

And ne'er again was seen.

.

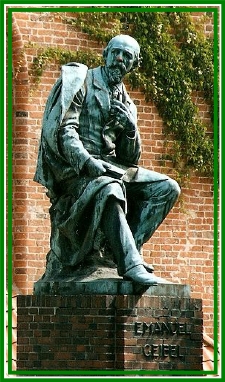

Goethe: “Mephisto’s Song of the Flea”

By Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827), “Aus Goethe’s Faust“, op. 75 no. 3 (1809). Translator: Anna Swanwick, 1850.,,

“Aus Goethes Faust: Mephistos Floh Lied”

A king there was once reigning,

Who had a goodly flea,

Him loved he without feigning,

As his own son were he!

His tailor then he summon’d,

The tailor to him goes;

Now measure me the youngster

For jerkin and for hose!

In satin and in velvet

Behold the younker dressed;

Bedizen’d o’er with ribbons,

A cross upon his breast.

Prime minister they made him,

He wore a star of state;

And all his poor relations

Were courtiers, rich and great.

The gentlemen and ladies

At court were sore distressed;

The queen and all her maidens

Were bitten by the pest,

And yet they dared not scratch them,

Or chase the fleas away.

If we are bit, we catch them

And crack them without delay..’

Goethe: “Eventide”

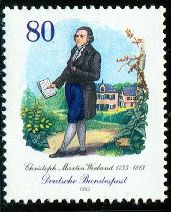

Excerpt, “German Poets and Their Times: A Series of Memoirs and Translations” by Joseph Gostwick with Portraits by C. Jager. 1874.

Goethe: “Solitude”

Excerpt, “THE POEMS OF GOETHE.” Translated in the Original Metres, by Edgar Alfred Bowring, C.B. 1853.

Goethe: “Coptic Song”

Excerpt, “THE POEMS OF GOETHE.” Translated in the Original Metres, by Edgar Alfred Bowring, C.B. 1853.

Goethe: “Before A Court Of Justice”

Excerpt, “THE POEMS OF GOETHE.” Translated in the Original Metres, by Edgar Alfred Bowring, C.B. 1853.

Goethe: To A Golden Heart

Excerpt, “The Sonnets of Europe: A Volume of Translations.” Selected and Arranged with Notes by Samuel Waddington. 1885.

Faust by Shelley: “May Day Night”

Excerpt, “German Poetry with The English Versions of The Best Translations.” Edited by H.E. Goldschmidt. 1869.

Illustrations by Harry Clarke.

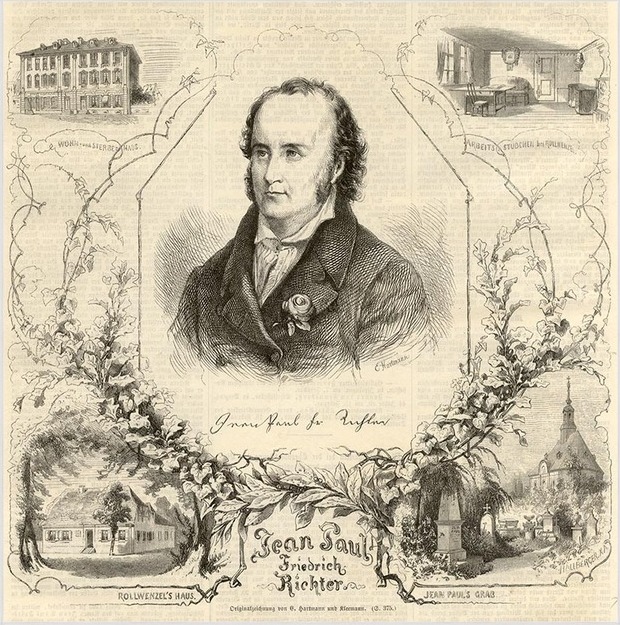

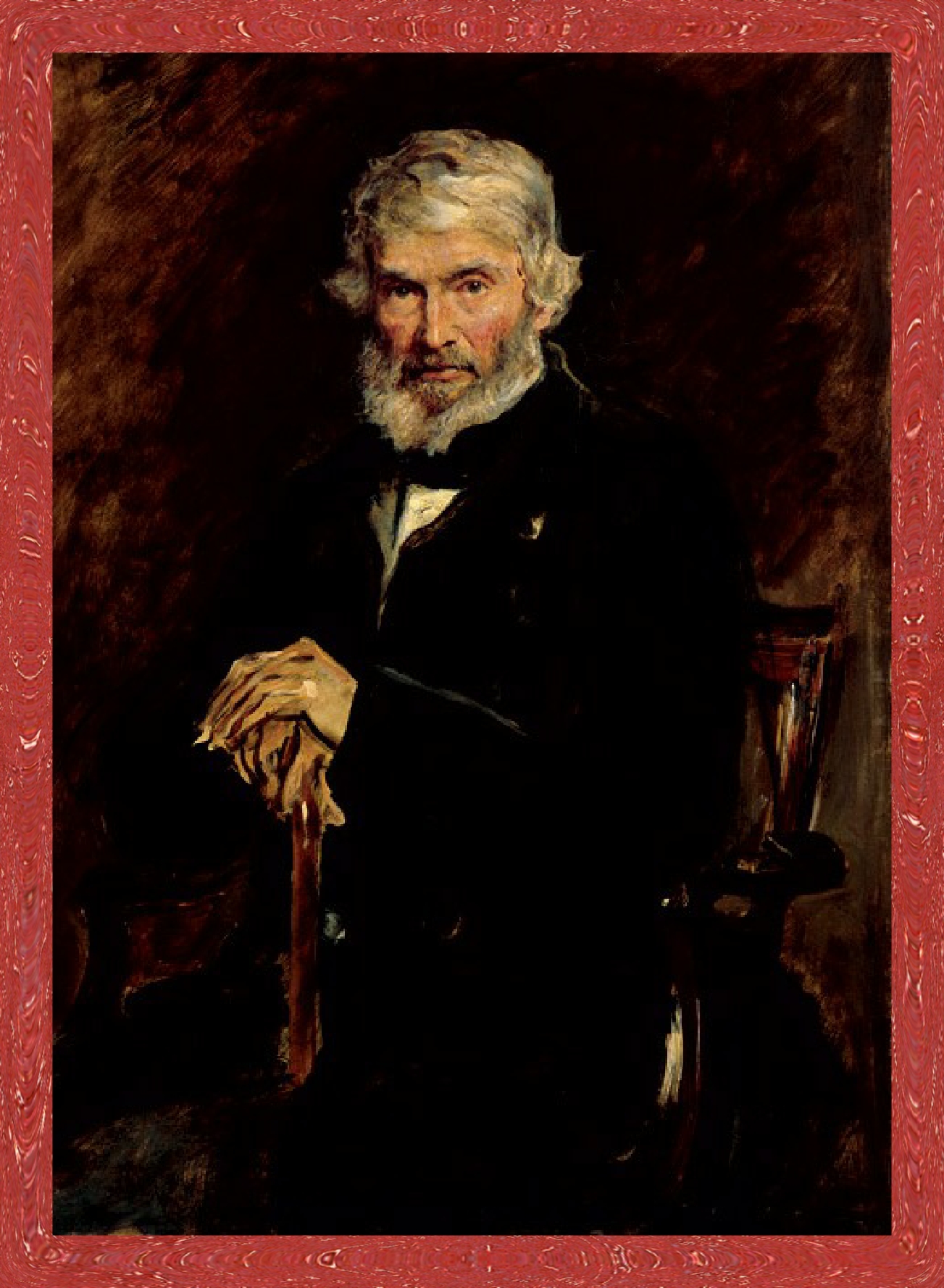

Madame de Staël: Goethe – Part 1 of 3

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. I, 265-272

That which was wanting to Klopstock was a creative imagination: he gave utterance to great thoughts and noble sentiments in beautiful verse; but he was not what might be called an artist. His intentions are weak; and the colours in which he invests them have scarcely even that plenitude of strength that we delight to meet with in poetry, and in all other arts which are expected to give to fiction the energy and originality of nature. Klopstock loses himself in the ideal: Goethe never gives up the earth; even in attaining the most sublime conceptions, his mind possesses vigour not weakened by sensibility.

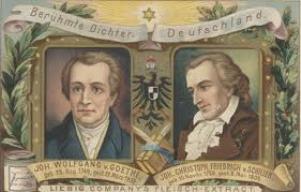

Goethe might be mentioned, as the representative of all German literature; not that there are no writers superior to him in different kinds of composition, but that he unites in himself alone all that distinguishes German genius; and no one besides is so remarkable for a peculiar species of imagination which neither Italians, English or French have ever attained.

Goethe having displayed his talents in composition of various kinds, the examination of his works will fill the greatest part of the following chapters; but a personal knowledge of the man who possesses such an influence over the literature of his country will, it appears to me, assist us the better to understand that literature.

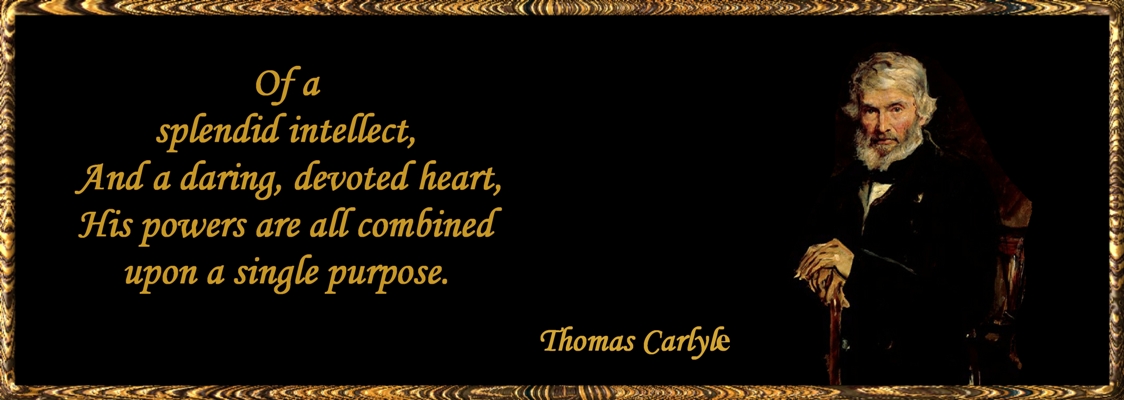

Goethe possesses superior talents for conversation; and whatever we may say, superior talents ought to enable a man to talk. We may, however, produce some examples of silent men of genius: timidity, misfortune, disdain, or ennui, are often the cause of it; but, in general, extent of ideas and warmth of soul naturally inspires the necessity of communicating our feelings to others; and those men who will not be judged by what they say, may not deserve that we should interest ourselves in what they think.

When Goethe is induced to talk, he is admirable; his eloquence is enriched with thought; his pleasantry is, at the same time, full of grace and of philosophy; his imagination is impressed by external objects, as was that of the ancient artists; nevertheless his reason possesses but too much the maturity of our own times. Nothing disturbs the strength of his mind, and even the defects of his character, ill-humour, embarrassment, constraint, pass like clouds round the foot of that mountain on the summit of which his genius is placed.

What is related of the conversation of Diderot may give some idea of that of Goethe; but, if we may judge by the writings of Diderot, the distance between these two men must be infinite. Diderot is the slave of his genius; Goethe ever holds the powers of his mind in subjection: Diderot is affected, from the constant endeavour to produce effect; but in Goethe we perceive disdain of success, and that to a degree that is singularly pleasing, even when we have most reason to find fault with his negligence.

Diderot finds it necessary to supply by philanthropy his want of religious sentiments: Goethe is inclined to be more bitter than sweet; but, above all, he is natural; and in fact, without this quality, what is there in one man that should have powers to interest another?

Goethe possesses no longer that resistless ardour which inspired him in the composition of Werter; but the warmth of his imagination is still sufficient to animate everything. It might be said, that he is himself unconnected with life, and that he describes it merely as a painter. He attaches more value, at present, to the pictures he presents to us, than to the emotions he experienced; time has rendered him a spectator. While he still bore a part in the active scenes of the passion, while he sufficed, in his own person, from the perturbations of the heart, his writings produced a more lively impression.

As we do not always best appreciate our own talents, Goethe maintains at present, that an author should be calm even when he is writing a passionate work; and that an artist should equally be cool, in order the more powerfully to act on the imagination of his readers. Perhaps, in early life, he would not have entertained this opinion; perhaps he was then enslaved by his genius, rather than its master; perhaps he then felt, that the sublime and heavenly sentiment being of transient duration in the heart of man, the poet is inferior to the inspiration which animates him, and cannot enter into judgment on it, so losing it at once.

At first we are astonished to find coldness, and even some stiffness, in the author of Werter; but when we can prevail on him to be perfectly at his ease, the liveliness of his imagination makes the restraint which we first felt entirely disappear. He is a man of universal mind, and impartial because universal; for there is no indifference in his impartiality: his is a double existence, a double degree of strength, a double light, which, on all subjects, enlightens at once both sides of the question. When it is necessary to think, nothing arrests his course; neither the age in which he lives, nor the habits he has formed, nor his relations with social life: his eagle glance falls decidedly on the object he observes.

If his soul had developed itself by actions, his character would have been more strongly marked, more firm, more patriotic; but his mind would not have taken so wide a range over every different mode of perception; passions or interests would then have traced out to him a positive path.

Goethe takes pleasure in his writings, as well as in his conversation, to break the thread which he himself has spun, to destroy the emotions he excites, to throw down the image he has forced us to admire. When, in his fictions, he inspires us with interest for any particular character, he soon shows the inconsistencies which are calculated to detach us from it. He disposes of the poetic world, like a conqueror of the real earth; and thinks himself strong enough to introduce, as nature sometimes does, the genius of destruction into his own works.

If he were not an estimable character, we should be afraid of that species of superiority which elevates itself above all things; which degrades, and then again raises up, which affects us, and then laughs at our emotion; which affirms and doubts by turns, and always with the same success.

I have said, that Goethe possessed in himself alone, all the principal features of German genius; they are all indeed found in him to an eminent degree: a great depth of ideas, that grace which springs from imagination, a grace far more original that than which is formed by the spirit of society; in short, a sensibility sometimes bordering on the fantastic, but far that very reason the more calculated to interest readers, who seek in books something that may give variety to their monotonous existence, and in poetry, impressions which may supply the want of real events.

If Goethe were a Frenchman, he would be made to talk morning till night: all the authors, who were contemporary with Diderot, went to derive ideas from his conversation, and afforded him at the same time an habitual enjoyment, from the admiration he inspired. The Germans know not how to make use of their talents in conversation, and so few people even among the most distinguished, have the habit of interrogating and answering, that society is scarcely at all esteemed among them; but the influence acquired by Goethe is not the less extraordinary.

There are a great many people in Germany who would think genius discoverable even in the direction of a letter, if it were written by him. The admirers of Goethe form a sort of fraternity, in which the rallying words serve to discover the adepts to each other. When foreigners also profess to admire him, they are rejected with disdain, if certain restrictions leave room to suppose that they have allowed themselves to examine works, which nevertheless gain much by examination.

No man can kindle such fanaticism without possessing great faculties, whether good or bad; for there is nothing but power, of whatever kind it may be, which men sufficiently dread to be excited by it to a degree of love so enthusiastic.

To be continued …

Part Two Part Three

Weimar’s Golden Days

Schiller vor Herzoginmutter Amalie, dem Herzogspaar Karl August und Luise, Goethe, Wieland, Herder, Musäus, den Brüdern Humboldt u.a. Farbdruck nach Gemälde von Theobald Reinhold Freiherr von Oer, 1860; Schloss Bellevue, Berlin.

Goethe: “The Treasure-Digger”

Excerpt, “The Poetry of Germany, Consisting from Upwards of Seventy of the Most Celebrated Poets.” Translated into English Verse by Alfred Baskerville. 1853.

Goethe: “Calm Sea”

Excerpt,“German Lyric Poetry: A Collection of Songs and Ballads.” Translated from the Best German Lyric Poets, with Notes by Charles Timothy Brooks. 1863.