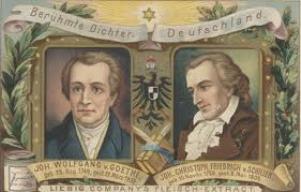

Madame de Staël on “The Robbers”

See here! See here!

The laws of the world have become mere dice-play;

The bonds of Nature are torn asunder.

The Demon of Discord has broken loose

And stalks about triumphant!

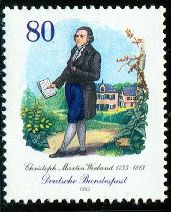

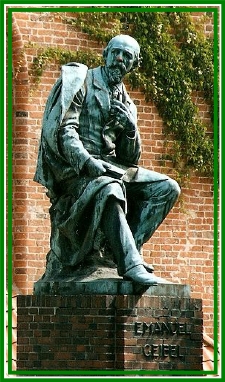

Schiller

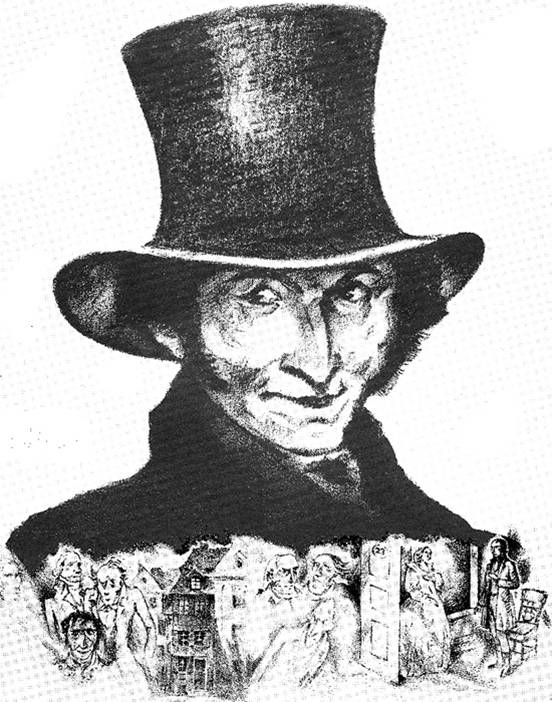

My newest book has arrived and I am pleased! The 1799 Render translation of Schiller’s first drama, “Die Räuber” ( published in 1781; first translated as The Robbers in 1792). At two hundred and nine years of age, the volume is a beauty! Bound in contemporary green calf, its spine is richly decorated and lettered in gilt (title and author vibrant!), its boards distinctively bordered in gilt and blind, with green marbled edges and end-papers, pages clean and bright, and a handsome frontispiece by Nagle!

Just hold an old book in your hand. Listen! It will whisper to you of ages past, if only you have the heart to hear!

But now, Comments from another antique source … DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation).

Schiller, in his earliest youth, possessed a fervour of genius, a kind of intoxication of sentiment, which misguided him. The “Conspiracy of Fiesco,” “Intrigue and Love,” and , lastly, “The Robbers,” all which have been performed in the French theatre, are works which the principle of art, as well as those of morality, may condemn; but from the age of five and twenty, his writings were pure and severe. The education of life depraves the frivolous, but perfects the reflecting mind.

“The Robbers” has been translated into French, but greatly altered; at first they omitted to take advantage of the date, which affixes an historical interest to the piece. The scene is placed in the 15th century, at the moment when the perpetual peace, by which all private challenges were forbidden, was published in the empire. This edict was no doubt productive of great advantage to the repose of Germany; but the young men of birth , accustomed to live in the midst of dangers, and rely upon their personal strength, fancied that they fell into a sort of shameful inertness when they subjected themselves to the authority of the laws. Nothing was more absurd that this conception; yet, as men are generally governed by custom, it is natural to be repugnant even to the best of changes, only because it is a change. Schiller’s Captain of the Robbers is less odious than if he were placed in the present times, for there was little difference between the feudal anarchy in which he lived, and the bandit life which he adopted; but it is precisely the kind of excuse which the author affords him, that renders his piece the more dangerous. It has produced, it must be allowed, a bad effect in Germany. Young men, enthusiastic admirers of the character and mode of living of the Captain of the Robbers, have tried to imitate him.

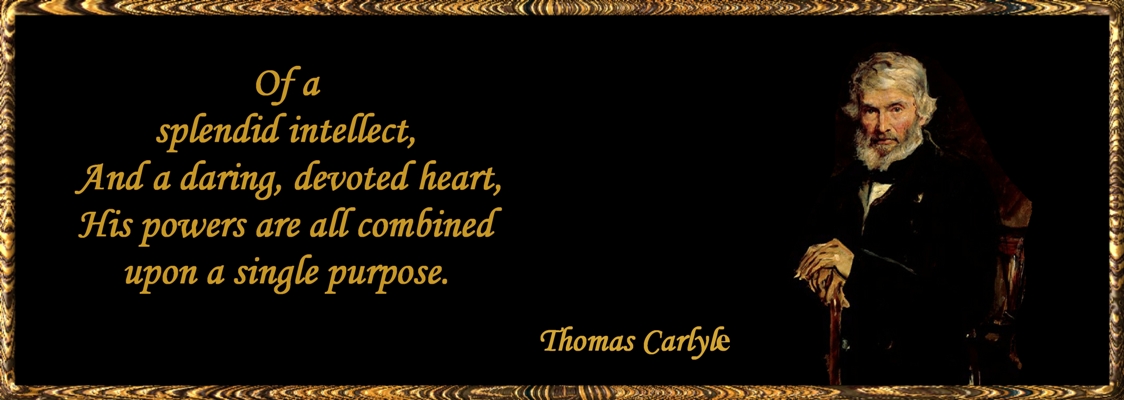

Their taste for a licentious life they honoured with the name of the love of liberty, and fancied themselves to be indignant against the abuses of social order, when they were only tired of their own private condition. Their essays in rebellion were merely ridiculous, yet have tragedies and romances more importance in Germany than in any other country. Every thing there is done seriously; and the lot of life is influenced by reading such a work, or seeing such a performance. What is admired in art, must be imitated into existence. Werther has occasioned more suicides than the finest woman in the world; and poetry, philosophy, in short all the ideal, have often more command over the Germans, than nature and the passions themselves.

The subject of “The Robbers” is the same with that of so many other fictions, all founded originally on the parable of the Prodigal. There is a hypocritical son, who conducts himself well in outward appearances, and a culpable son, who possesses good feelings among his faults. This contrast is very fine in a religious point of view, because it bears witness to us that God reads our hearts; but is nevertheless objectionable in inspiring too much interest in favor of a son who deserted his father’s house. It teaches young people with bad heads universally to boast of the goodness of their hearts, although nothing is more absurd than for men to attribute to themselves virtues, only because they have defects; this negative pledge is very uncertain, since it never can follow from their wanting reason that they are possessed of sensibility: Madness is often only an impetuous excess of self-love.

The character of the hypocritical son, such as Schiller has represented him, is much too odious. It is one of the faults of very young writers to sketch with too hasty a pencil; the gradual shades in painting are taken for timidity of character, when, in fact, they constitute a proof of the maturity of talent. If the personages of the second rank are not painted with sufficient exactness, the passions of the chief of the robbers are admirably expressed. The energy of this character manifests itself in turns in incredulity, religion, love and cruelty. Having been unable to find a place where to fix himself in his proper rank, he makes to himself an opening through the commission of a crime; existence is for him sort of a delirium, heightened sometimes by rage, and sometimes by remorse. The love scenes between the young girl and the chief of the robbers, who was to have been her husband, are admirable in point of enthusiasm and sensibility; there are few situations more pathetic than that of this perfectly virtuous woman, always attached from the bottom of her soul to him whom she loved before he became criminal. The respect which a woman is accustomed to feel for the man she loves is changed into a sort of terror and of pity; and one would say that the unfortunate female flatters herself with the thought of becoming the guardian angel of her guilty lover, in heaven, now when she can never more hope to be the happy companion of his pilgrimage on earth.

Schiller’s play cannot be fairly appreciated by the French translation. In this they have preserved only what may be called the pantomime of action; the originality of the characters has vanished, and it is that alone which can give life to fiction; the finest tragedies would degenerate into melo-drames, when stripped of the animated colouring of sentiments and passions. The force of events is not enough to unite the spectator with the persona represented; let them love, or let them kill one another, it is all the same to us, if the author has failed of exciting our sympathies in their favour.

Madame de Staël