Bismarck: Letters to Johanna 2/3

Excerpt, “German Classics of the 19th and 20th Centuries,” Vol. X, 1914; translator Charlton T. Lewis et al.

If we are not unmeasured in our claims

And do not imagine we have conquered the world,

We shall achieve a peace that is worth the trouble.

Otto von Bismarck

Hohenmauth, Monday, September 7, ’66.

Do you remember, sweetheart, how we passed through here nineteen years ago, on the way from Prague to Vienna? No mirror showed the future then, nor in 1852, when I went over this railway with good Lynar. How strangely romantic are God’s ways! We are doing well, in spite of Napoleon; if we are not unmeasured in our claims and do not imagine we have conquered the world, we shall achieve a peace that is worth the trouble. But we are as easily intoxicated as disheartened, and it is my thankless part to pour water into the foaming wine, and to insist that we do not live alone in Europe, but with three other powers which hate and envy us.

The Austrians hold position in Moravia, and we are bold enough to announce our headquarters for tomorrow at the point where they are now. Prisoners still keep passing in, and cannon, one hundred and eighty from the 3d to today. If they bring up their southern army, we shall, with God’s gracious help, defeat it too; confidence is universal. Our people are ready to embrace one another, every man so deadly in earnest, calm, obedient, orderly, with empty stomach, soaked clothes, wet camp, little sleep, shoe-soles dropping off, kindly to all, no sacking or burning, paying what they can and eating mouldy bread.

There must surely be a solid basis of fear of God in the common soldier of our army, or all this could not be. News of our friends is hard to get; we lie miles apart from one another, none knowing where the other is, and nobody to send–that is, men might be had, but no horses. For four days I have had search made for Philip, who was slightly wounded by a lance-thrust in the head, as Gerhard wrote me, but I can’t find out where he is, and we have now come thirty-seven miles farther.

The King exposed himself greatly on the 3d and it was well I was present, for all the warnings of others had no effect, and no one would have dared to talk so sharply to him as I allowed myself to do on the last occasion, which gave support to my words, when a knot of ten cuirassiers and fifteen horses of the Sixth Cuirassier Regiment rushed confusedly by us, all in blood, and the shells whizzed around most disagreeably close to the King.

He cannot yet forgive me for having blocked for him the pleasure of being hit. “At the spot where I was forced by order of the supreme authority to run away,” were his words only yesterday, pointing his finger angrily at me. But I like it better so than if he were excessively cautious. He was full of enthusiasm over his troops, and justly so rapt that he seemed to take no notice of the din and fighting close to him, calm and composed as at the Kreuzberg, and constantly meeting battalions that he must thank with “Good-evening, grenadiers,” till we were actually by this trifling brought under fire again. But he has had to hear so much of this that he will stop it for the future, and you may feel quite easy; indeed, I hardly believe there will be another real battle.

When you have of anybody no word whatever, you may assume with confidence that he is alive and well; for if acquaintances are wounded it is always known at latest in twenty-four hours. We have not come across Herwarth and Steinmetz at all, nor has the King. Schreck, too, I have not seen, but I know they are well. Gerhard keeps quietly at the head of his squadron, with his arm in a sling.

Farewell–I must to business.

Your faithfullest v.B.

~~~~~

Zwittau, Moravia, July 11, ’66.

Dear Heart,

I have no inkstand, all of them being in use; but for the rest I get on well, after a good sleep on a camp bed with air mattress; roused at eight by a letter from you. I went to bed at eleven. At Königgrätz I rode the big sandy thirteen hours in the saddle without feeding him. He bore it very well, did not shy at shots nor at corpses, cropped standing grain and plum-leaves with zest at the most trying moments, and kept up an easy gait to the last, when I was more tired than the horse. My first bivouac for the night was on the street pavement of Horic, with no straw, but helped by a carriage cushion.

It was full of wounded; the Grand Duke of Mecklenburg found me and shared his chamber with me, Reuss, and two adjutants, and the rain made this very welcome to me. About the King and the shells I have written you already. All the generals had a superstition that they, as soldiers, must not speak to the King of danger, and always sent me off to him, though I am a major, too. They did not venture to speak to his reckless Majesty in the serious tone which at last was effectual. Now at last he is grateful to me for it, and his sharp words, “How you drove me off the first time,” etc., are an acknowledgment that I was right. Nobody knew the region, the King had no guide, but rode right on at random, till I obtruded myself to show the way.

Farewell, my heart. I must go to the King.

Your most faithful v.B.

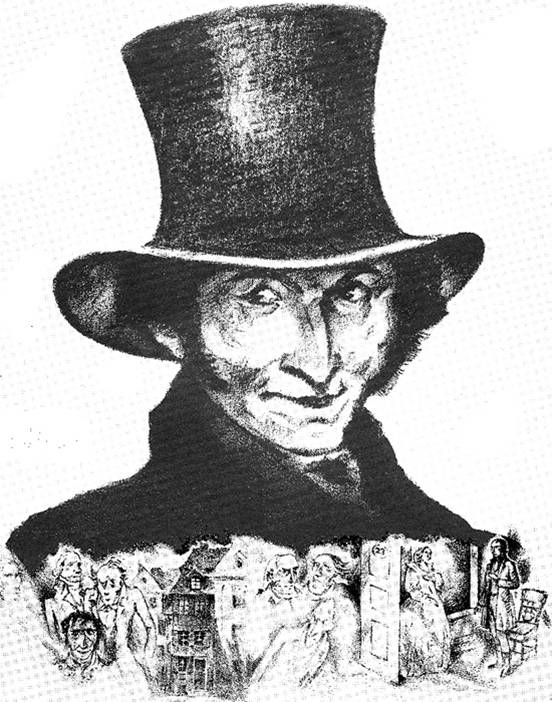

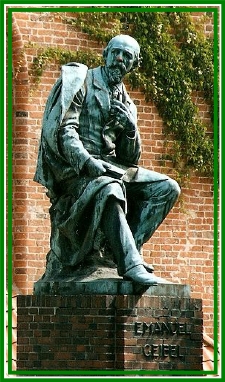

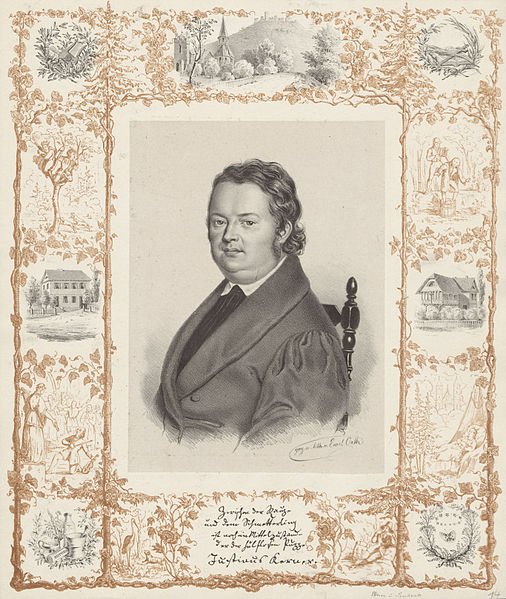

Minister-President Otto von Bismarck; Minister of War Albrecht von Roon;

Helmuth Karl von Moltke, Chief of the Prussian General Staff.