Category Archives: de Staël

Madame de Staël: “Of a Romantic Bias in the Affections of the Heart”

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. III, 230-235.

Reading Madame de Staël’s “Delphine”

Of a Romantic Bias in the Affections of the Heart

The English philosophers have founded virtue, as we have said, upon feeling, or rather upon the moral sense; but this system has no connection with the sentimental morality of which we are here talking: this morality (the name and idea of which hardly exist out of Germany) has nothing philosophical about it; it only makes a duty of sensibility, and leads to the contempt of those who are deficient in that quality.

Doubtless, the power of feeling love is very closely connected with morality and religion: it is possible then that our repugnance to cold and hard minds is a sublime sort of instinct — an instinct which apprises us, that such beings, even when their conduct is estimable, act mechanically, or by calculation; and that it is impossible for any sympathy to exist between us and them. In Germany, where it is attempted to reduce all impressions into precepts, every thing has been deemed immoral which was destitute of sensibility — nay, which was not of a romantic character. Werther had brought exacted sentiments so much into fashion, that hardly any body dared to show that he was dry and cold of nature, even when he was condemned to such a nature in reality.

From thence arose that forced sort of enthusiasm for the moon, for forests, for the country, and for solitude; from thence those nervous fits, that affectation in the very voice, those looks which wished to be seen; in a word, all that apparatus of sensibility, which vigorous and sincere minds disdain.

The author of Werther was the first to laugh at these affectations; but, as ridiculous practices must be found in all countries, perhaps it is better that they should consist in the somewhat silly exaggeration of what is good, than in the elegant pretension to what is evil. As the desire of success is unconquerable among men, and still more so among women, the pretensions of mediocrity are a certain sign of the ruling taste at such an epoch, and in such a society; the same persons who displayed their sentimentality in Germany, would have elsewhere exhibited a levity and superciliousness of character.

The extreme susceptibility of the German character is one of the great causes of the importance they attach to the least shades of sentiment; and this susceptibility frequently arises from the truth of the affections. It is easy to be firm when we have no sensibility: the sole quality which is then necessary is courage; for a well-regulated severity must begin with self: but, when the proofs of interest in our welfare, which others give or refuse us, powerfully influence our happiness, we must have a thousand times more irritability in our hearts than those who use their friends as they would an estate, and endeavor solely to make them profitable.

At the same time we ought to be on our guard against those codes of subtle and many-shaded sentiment, which the German writers have multiplied in such various manners, and with which their romances are filled. The Germans, it must be confessed, are not always perfectly natural. Certain of their own uprightness, of their own sincerity in all the real relations of life, they are tempted to regard the affected love of the beautiful as united to the worship of the good, and to indulge themselves, occasionally, in exaggerations of this sort, which spoil every thing.

This rivalship of sensibility, between some German ladies and authors, would at the bottom be innocent enough, if the ridiculous appearance which it gives to affectation did not always throw a kind of discredit upon sincerity itself. Cold and selfish persons find a peculiar pleasure in laughing at passionate affectations; and would wish to make everything appear artificial which they do not experience. There are even persons of true sensibility whom this sugared sort of exaggeration cloys with their own impressions; and their feelings become exhausted, as we may exhaust their religion, by tedious sermons and superstitious practices.

It is wrong to apply the positive ideas which we have of good and evil to the subtilties of sensibility. To accuse this or that character of their deficiencies in this respect, is likely making it a crime not to be a poet. The natural susceptibility of those who think more than they act, may render them unjust to persons of a different description. We must possess imagination to conjecture all that the heart can make us suffer, and the best sort of people in the world are often dull and stupid in this respect: they march right across our feelings, as if they were treading upon flowers, and wondering that they fade away.

Are there not men who have no admiration for Raphael, who hear music without emotion, to whom the ocean and the heavens are but monotonous appearances? How then should they comprehend the tempests of the soul?

Are not even those who are most endowed with sensibility sometimes discouraged in their hopes? May they not be overcome by a sort of inward coldness, as if the Godhead was retiring from their bosoms? They remain not less faithful to their affections; but there is no more incense in the temple, no more music in the sanctuary, no more emotions in the heart. Often also does misfortune bid us silence in ourselves this voice of sentiment, harmonious or distracting in its tone, as it agrees, or not, with our destiny.

It is then impossible to make a duty of sensibility; for those who own it suffer so much from its possession, as frequently to have the right and the desire to subject it to restraint.

Nations of ardent character do not talk of sensibility without terror: a peaceable and dreaming people believe they can encourage it without alarm. For the rest, it is possible, that this subject has never been written upon with perfect sincerity; for every one wishes to do himself honour by what he feels, or by what he inspires. Women endeavor to set themselves out like a romance; men like a history; but the human heart is still far from being penetrated in its most intimate relations.

At one time or another, perhaps, somebody will tell us sincerely all he has felt; and we shall be quite astonished at discovering, that the greater part of maxims and observations are erroneous, and that there is an unknown soul at the bottom of that which we have been describing.

Madame de Staël

Madame de Staël: Goethe – Pt. 3

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. III, 138-146. Illustrations by Johann Heinrich Ramberg (1763-1840)

Goetz of Berlichingen

The dramatic career of Goethe may be considered in two different lights. The pieces he designed for representation have much grace and facility, but nothing more. In those of his dramatic works, on the contrary, which it is very difficult to perform, we discover extraordinary talent. The genius of Goethe cannot bound itself to the limits of the theatre; and, endeavoring to subject itself to them, it loses a portion of originality, and does not entirely recover it till again at liberty to mix all styles together as it chooses.

No art, whatever it can be, can exist without certain limits; painting, sculpture, architecture, are subject to their own peculiar laws, and in like manner the dramatic art produces its effect only under certain conditions; conditions which sometimes restrain both thought and feeling; and yet the influence of the theatre is so great upon the assembled audience, that one is not justified in refusing to employ the power it possesses, by the pretext that it exacts sacrifices which the imagination left to itself would not require.

As there is no metropolis in Germany to collect together all that is necessary to form a good theatre, dramatic works are much oftener read than performed: and thence it follows that authors compose their dramas with a view to the effect in reading, not in acting.

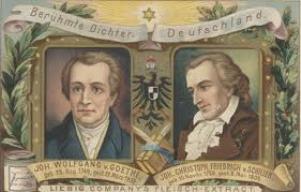

Goethe is almost always making new experiments in literature. When the German taste appears to him to lean towards an excess in any respect, he immediately endeavors to give it an opposite direction. He may be said to govern the understandings of his contemporaries, as an empire of his own, and his works may be called decrees, by turns authorizing or banishing the abuses of art.

Goethe was tired of the imitation of French pieces in Germany, and with reason; for even a Frenchman might be equally tired of it. He therefore composed an historical tragedy, in the manner of Shakespeare, Goetz of Berlichingen. This piece was not destined for the stage; but it is nevertheless capable of representation, as are all those of Shakespeare of the same description.

Goethe has chosen the same historical epoch as Schiller in his play of the Robbers; but, instead of presenting a man who has set himself free from all the ties of moral and social order, he has painted an old knight, under the reign of Maximilian, still defending the chivalrous manners and the feudal condition of the nobility, which gave so high an ascendant to their personal valour. Goetz of Berlichingen was surnamed the “iron-handed” because having lost his right hand in war, he had one made for him with springs, by the aid of which he held and managed his lance with dexterity.

He was a knight renowned in his time for courage and loyalty. This model is happily chosen to represent what was the independence of nobles before the authority of government became coercive on all men. In the middle ages, every castle was a fortress, every noble a sovereign.

The establishment of standing armies, and the invention of artillery, effected a total change in social order; a sort of abstract power was introduced under the name of the state or the nation; but individuals lost, by degrees, all their importance. A character like that of Goetz must have suffered from this change whenever it took place.

The military spirit has always been of a ruder cast in Germany than anywhere else, and it is there that we might figure to ourselves, as real, those men of iron whose images are still to be seen in the arsenals of the empire. Yet the simplicity of chivalrous manners is painted in Goethe’s tragedy with many charms.

This aged Goetz, living in the midst of battles, sleeping in his armour, continually on horseback, never resting except when besieged, employing all his resources for war; contemplating nothing besides; this aged Goetz, I say, gives us the highest idea of the interest and activity which human life possessed in those ages. His virtues, as well as his defects, are strongly marked; nothing is more generous than his regard for Weislingen, once his friend, then his adversary, and often engaged even in acts of treason against him.

The sensibility shewn by an intrepid warrior, awakens the soul in an entirely new manner; we have time to love in our inactive state of existence; but these lightnings of passion which enable us to read in the bottom of the heart through the medium of a stormy existence cause a sentiment of profound emotion. We are so afraid of meeting with affectation in the noblest gift of heaven, sensibility, that we sometimes prefer in the expression of it even rudeness itself as the pledge of sincerity.

The wife of Goetz presents herself to the imagination like an old portrait of the Flemish school, in which the dress, the look, the very tranquility of the attitude, announce a woman submitted to the will of her husband, knowing him only, admiring him only, and believing herself destined to serve him, as he is to defend her.

By way of contrast to this most excellent woman, we have a creature altogether perverse, Adelaide, who seduces Weislingen, and makes him fail in the promise he had given to his friend; she marries, and soon after proves faithless to him. She renders herself passionately beloved by her page, and bewilders the imagination of this unhappy young man to such a degree as to prevail upon him to give a poisoned cup to his master.

These features are strong, but perhaps it is true that when the manners of a nation are generally very pure, the woman who estranges herself from them soon becomes entirely corrupted, the desire of pleasing is in our days no more than a tie of affection and kindness; but in the strict domestic life of a former age, it was an error capable of involving all others in its consequences. This guilty Adelaide gives occasion to one of the finest scenes in the play, the sitting of the secret tribunal.

Mysterious judges, unknown to one another, always masked, and meeting at night, punished in silence, and only engraved on the poniard which they plunged into the bosom of the culprit this terrible motto: THE SECRET TRIBUNAL.

They acquainted the condemned person with his sentence by having it cried three times under his window, Woe, woe, woe! Thus was the unfortunate man given to know that, everywhere, in the stranger, in the fellow citizen, in the kinsman even, he might find his murderer.

In the crowd, and in solitude, in the city, and in the court, all places were filled by the invisible presence of that armed conscience which persecuted the guilty. One may conceive how necessary this terrible institution might have been, at a time when every man was powerful against all men, instead of all being invested with the power which they ought to possess over each individual.

It was necessary that justice should surprise the criminal before he was able to defend himself; but this punishment hovered in the air like an avenging shade, this mortal sentence which might be harboured even in the bosom of a friend, inspired an invincible terror.

There is another fine situation — that in which Goetz, in order to defend himself in his castle, commands the lead to be stripped from the windows to melt into balls. There is in this character a contempt of futurity, and an intenseness of strength at the present moment that are altogether admirable. At last, Goetz beholds all his companion in arms perish; he remains wounded, a prisoner, and having only his wife and sister left by his side.

He is surrounded by women alone, he who desired to live among men, among men of unconquerable spirits, that he might exert with them the force of his character and the strength of his arm. He thinks on the name that he must leave behind him; he reflects, now that he is about to die. He asks to behold the sun once more, he thinks on God, who never before occupied his thoughts, but of whose existence he never doubted, and dies with gloomy courage, regretting his warlike pleasures more than life itself.

This play is much liked in Germany; the national manner and customs of times of old, are faithfully represented by it, and whatever touches on ancient chivalry moves the hearts of the Germans. Goethe, the most careless of all men, because he is sure of leading the taste of his audience, did not give himself the trouble even of putting his play into verse; it is the sketch of a great picture, but hardly enough finished even as a sketch.

One perceives in the writer so great an impatience of all that can be thought to bear a resemblance to affectation, that he distains even the art that is necessary to give a durable form to his compositions. There are marks of genius scattered here and there through his drama, like the touches of Michaelangelo’s pencil; but it is a work defective, or rather which makes us feel the want of many things. The reign of Maximilian, during which the principal event is supposed to pass, is not sufficiently marked.

In short, we may venture to censure the author for not having enough exercised his Imagination in the form and language of the piece. It is true that he has intentionally and systematically abstained from indulging it; he wished the drama to be the action itself; forgetting that the charm of the ideal is that which ought to preside over all things in dramatic works.

The characters of tragedies are always in danger of being either common or factitious, and it is incumbent on genius to preserve them equally from each extreme. Shakespeare, in his historical pieces, never ceased to be a poet, nor Racine to observe with exactness the manners of the Hebrews in his lyrical tragedy of Athalie.

The dramatic talent can dispense neither with nature nor with art; art is totally distinct from artifice, it is a perfectly true and spontaneous inspiration, which spreads an universal harmony over particular circumstances, and the dignity of lasting remembrances over fleeting moments.

To be continued…

Madame de Staël: Goethe – Pt. 2

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. 1, 349-358.

Goethe stands unrivaled in the art of composing elegies, ballads, stanzas, &c.; his detached pieces have a very different merit from those of Voltaire. The French poet has transfused in his verse the spirit of the most brilliant society; the German, by a few slight touches, awakens in the soul profound and contemplative impressions.

Goethe is to the highest degree natural in this species of composition; and not only so when he speaks from his own impressions, but even when he transports himself to new climates, customs, and situations, his poetry easily assimilates itself with foreign countries; he seizes, with a talent perfectly unique, all that pleases in the national songs of each nation; he becomes , when he chooses it, a Greek, an Indian, or a Morlachian.

We have often mentioned that melancholy and meditation which characterises the poets of the north: Goethe, like all other men of genius, unites in himself most astonishing contrast; we find in his works many traces of character peculiar to the inhabitants of the south; they are more awakened to the pleasures of existence, and have at once a more lively and tranquil enjoyment of nature than those of the north; their minds have not less depth, but their genius has more vivacity; we find in it a certain sort of naivete, which awakens at once the remembrance of ancient simplicity with that of the middle ages: it is not the naivete of innocence , but that of strength.

We perceive in Goethe’s poetical compositions, that he disdains the crowd of obstacles, criticisms, and observations, which may be opposed to him. He follows his imagination wherever it leads him, and a certain predominant pride frees him from the scruples of self-love. Goethe is in poetry an absolute master of nature, and most admirable when he does not finish his pictures; for all his sketches contain the germ of a fine fiction, but his finished fictions do not always equally convey the idea of a good sketch.

In his elegies composed at Rome, we must not look for descriptions of Italy; Goethe scarcely does whatever is expected from him, and when there is anything pompous in an idea it displeases him: he wishes to produce effect by an untrodden path hitherto unknown both to himself and to the reader. His elegies describe the effect of Italy on his whole existence, that delirium of happiness resulting from the influence of a serene and beautiful sky. He relates his pleasures, even of the most common kind, in the manner of Propertius; and from time to time some fine recollections of that city which was once the mistress of the world give an impulse to the imagination, the more lively because it was not prepared for it.

He relates, that he once met in the Campania of Rome a young woman suckling her child, and seated on the remains of an ancient column; he wished to question her on the subject of the ruins with which her hut was surrounded: but she was ignorant of everything concerning them, wholly devoted to the affections which filled her soul; she loved, and to her the present moment was the whole of existence.

We read in a Greek author, that a young girl, skillful in the art of making nosegays of flowers, entered into a contest with her lover, Pausias, who knew how to paint them. Goethe has composed a charming idyl on that subject. The author of that idyl is also the author of Werther. Goethe has run through all the shades and gradations of love, from the sentiment which confers grace and tenderness, to that despair which harrows up the soul but exalts genius. After having made himself a Greek in Pausias, Goethe conducts us to Asia in a most charming ballad, called the Bayadere.

An Indian diety (Mahadoch) clothes himself in a mortal form, in order to judge of the pleasures and pains of men from his own experience. He travels through Asia, observes both the great and the lower classes of people; and as one evening, on leaving a town, he was walking on the banks of the Ganges, he is stopped by a Bayadere, who persuades him to rest himself in her habitation. There is so much poetry, colours so truly oriental in his manner of painting the dances of this Bayadere, the perfumes and flowers with which she is surrounded, that we cannot, from our own manners, judge of a picture so perfectly foreign to them.

The Indian diety inspires this erring female with true love, and touched with that return towards virtue which sincere affection should always inspire, he resolves to purify the soul of the Bayadere by the trials of misfortune.

When she awakes, she finds her lover dead by her side; the priests of Brama carry off the lifeless body to consume it on the funeral pile; the Bayadere endeavors to threw herself on it with him she loves, but is repulsed by the priests, because, not being his wife, she has no right to die with him. After having felt all the anguish of love and of shame, she throws herself on the pile in spite of the Bramins. The god receives her in his arms; he darts through the flames, and carries the object of his tenderness, now rendered worthy of his choice, with him to heaven.

Zelter, an original musician, has set this romance to an air by turns voluptuous and solemn, which suits the words extremely well. Where we hear it, we think ourselves in India, surrounded with all its wonder; and let it not be said that a ballad is too short a poem to produce such an effect. The first notes of an air, the first verse of a poem, transports the imagination to any distant age or country; but if a few words are thus powerful, a few words can also destroy the enchantment. Magicians formerly could perform or prevent prodigies by the help of a few magical words.

It is the same with the poet: he may call up the past, or make the present appear again, according as the expressions he makes use of are, or are not, conformable to the time or country which is the subject of his verse, according as he observes or neglects local coloring, and those little circumstances so ingeniously inverted, which, both in fiction and reality, exercise the mind in the endeavor to discover truth where it is not specifically pointed out to us.

Another ballad of Goethe’s produces a delightful effect by the most simple means: it is “the Fisherman.” A poor man, on a summer’s evening, seats himself on the bank of a river, and, as he throws in his line, contemplates the clear and limpid tide which gently flows and bathes his naked feet. The nymph of the stream invites him to plunge himself into it; she describes to him the delightful freshness of the water during the heat of the summer, the pleasure which the sun takes in cooling itself at night in the sea, the calmness of the moon when its rays repose and sleep on the bosom of the stream: at length the fisherman attracted, seduced, drawn on, advances near the nymph, and forever disappears.

The story on which this ballad is founded is trifling; but what is delightful in it is, the art of making us feel the mysterious power which may proceed from the phenomena of nature. It is said there are persons who discover springs hidden under the earth by the nervous agitation which they cause in them: in German poetry we often think we discover that miraculous sympathy between man and the elements. The German poet comprehends nature not only as a poet, but as a brother; and we might almost say that the bonds of family union connect him with the air, the water, flowers, trees, in short, all the primary beauties of the creation.

There is no one who has not felt the undefinable attraction which we experience when looking on the waves of the sea, whether from the charm of their freshness, or from the ascendancy which an uniform and perpetual motion insensibly acquires over our transient and perishable existence. This ballad of Goethe’s admirably expresses the increasing pleasure we derive from contemplating the pure waters of a flowing stream: the measure of the rhythm and harmony is made to imitate the motion of the waves, and produces an analogous effect on the imagination. The soul of nature discovers itself to us in every place and under a thousand different forms.

The fruitful country and the unpeopled desert, the sea as well as the stars, are all subjected to the same laws, and the man contains within himself sensation and occult powers, which correspond with the day, with the night, and with the storm: it is this secret alliance with our being with the wonders of the universe which gives to poetry its true grandeur. The poet knows how to restore the union between the natural and the moral world: his imagination forms a connecting tie between the one and the other.

There is much gaiety in several of Goethe’s pieces: but we seldom find in them that sort of pleasantry to which we have been accustomed: he is sooner struck by the imagery of nature than by ridiculous circumstances; with a singular instinct, he points out the originality of animals, always new yet never varying. “The Menagerie of Lily,” and “The Wedding Song in the Old Castle,” describe aminals, not like men, in La Fontaine’s manner, but like fantastic creatures, the sports of Nature.

Goethe also finds in the marvelous a source of pleasantry, the more gratifying because we discover in it no serious aim. A song entitled “The Pupil of the Sorcerer” also deserves to be mentioned. The pupil of a sorcerer having heard his master mutter some magical words, by the help of which he gets a broomstick to tend on him, recollects those words, and commands the broomstick to go and fetch him water from the river, to wash his house. The broomstick sets off and returns, brings one bucket, then another, and then another, and so on without ceasing.

The pupil wants to stop it, but he has forgot the words necessary to that purpose: the broomstick, faithful to its office, still goes to the river and still draws up the water, which is thrown on the house at the risk of inundating it. The pupil, in his fury, takes an ax and cuts the broomstick in two; the two parts of the stick then become two servants instead of one, and go for water which they throw into the apartments as if in emulation of each other, with more zeal than ever.

In vain the pupil scolds these stupid sticks; they continue their business without ceasing, and the house would have been lost, had not the master arrived in time to assist his pupil, at the same time laughing heartily at his ridiculous presumption. An awkward imitation of the great secrets of art is very well depicted in this little scene.

To be continued …

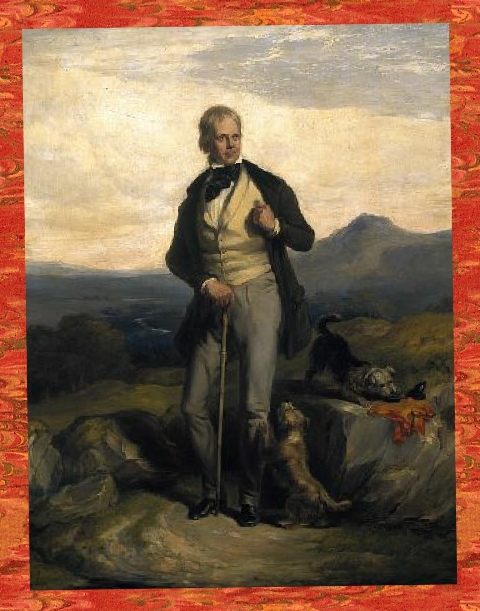

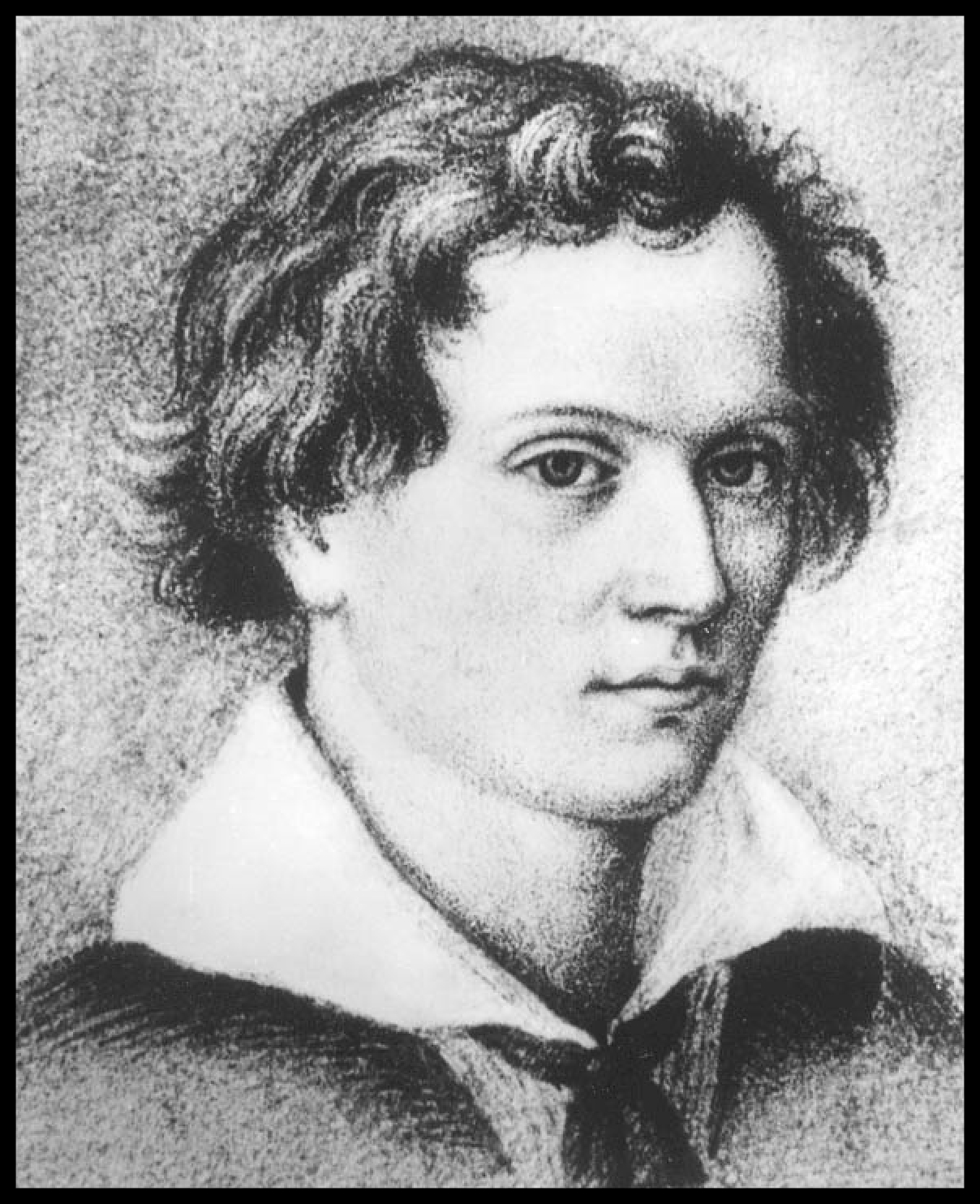

Goethe, 1775-1776

By Georg Melchior Kraus

Madame de Staël: Winckelmann

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. I, 258-264.

Johann Joachim Wincklemann was the man who in Germany brought about an entire revolution in the manner of considering the arts, and literature also as connected with the arts. I shall speak of him elsewhere under the relation of his influence on the arts; but his style certainly places him in the first rank of German writers.

This man, who at first knew antiquity only by books, was desirous of contemplating its noble remains. He felt himself attracted with ardour towards the south. We still frequently find in German imagination some traces of that love of the sun, that weariness of the north, which formerly drew so many northern nations into the countries of the south. A fine sky awakens sentiments similar to the love we bear to our country. When Winckelmann, after a long abode in Italy, returned to Germany, the sight of snow, of the pointed roofs which it covers, and of smoky houses, filled him with melancholy. He felt as if he could no longer enjoy the arts, when he no longer breathed the air which gave them birth.

What contemplative eloquence do we not discover in what he has written on the Apollo Belvedere and the Laocoon! His style is calm and majestic as the object of his consideration. He gives to the art of writing the imposing dignity of ancient monuments, and his description produces the same sensation as the statue itself. No one before him had united such exact and profound observation with admiration so animated; as it is thus, only, that we can comprehend the fine arts. The attention they excite must be awakened by love; and we must discover in the chef-d-oeuvres of genius, as we do in the features of a beloved object, a thousand charms, which are revealed to us by the sentiments they inspire.

Some poets, before Winckelmann, had studied Greek tragedies, with the purpose of adapting them to our theatres. Learned men were known, whose authority was equal to that of books; but no one had hitherto (to use the expression) rendered himself a pagan in order to penetrate antiquity. Winckelmann possesses the defects and advantages of a Grecian amateur; and we feel in his writings the adoration of beauty, such as it existed in a nation where it so often obtained the hours of apotheosis.

Imagination and learning equally lent their different lights to Winckelmann: before him it was thought that they mutually excluded each other. He has shewn us that to understand the ancients, one was as necessary as the others. We can give life to objects of art only by an intimate acquaintage with the country and with the epoch in which they existed. We are not interested by features which are indistinct. To animate recitals and fictions, where past ages are the theatre, learning must even assist the imagination, and render it, if possible, a spectator of what it is to paint, and a contemporary of what it relates.

Zadig guessed by some confused traces, some words half torn, at circumstances which he deduced from the slightest indications. It is thus, that through antiquity we must take learning for our guide: the vestiges which we perceive are interrupted, effaced, difficult to lay hold of; but by making use at once of imagination and study, we bring back time, and renew existence.

When we appeal to tribunals to decide on the truth of a fact, it is sometimes a slight circumstanced which makes it clear. Imagination is in this respect like a judge; a single word, a custom, an allusion found in the works of the ancients, serves it as a light, by which it arrives at the knowledge of perfect truth.

Winckelmann knew how to apply to his inspection of the monuments of the arts that spirit of judgment which leads us to the knowledge of men: he studied the physiognomy of the statue as he would have done that of a human being. He seized with great justness the slightest observations, from which he knew how to draw the most striking conclusions. A certain physiognomy, an emblematical attribute, a mode of drapery, may at once cast an unexpected light on the longest researches. The locks of Ceres are thrown back with a disorder that would be unsuitable to the character of Minerva; the loss of Proserpine has for ever troubled the mind of her mother.

Minos, the son and disciple of Jupiter, has in our medals the same features as his father; nevertheless, the calm majesty of the one, and the severe expression of the other, distinguish the sovereign of the gods from the judge of men. The Torso is a fragment of the stature of Hercules deified; of him, who received from Hebe the cup of immortality; while the Hercules Farnese yet possesses only the attributes of a mortal; each contour of the Torso, as energetic as this but more rounded, still characterizes the strength of the hero; but of the hero who, placed in heaven, is thenceforth freed from the rude labours of the earth.

All is symbolical in the arts, and natures herself under a thousand different appearances in those pictures, in that poetry, where immobility must indicate motion, where the inmost soul must be externally displayed, and where the existence of a moment must last to eternity.

Winckelmann has banished from the fine arts in Europe the mixture of ancient and modern taste. In Germany, his influence has been still more displayed in literature than in the arts. We shall, in what follows, be led to examine, whether the scrupulous imitation of the ancients is compatible with natural originality; or rather, whether we ought to sacrifice that originality in order to confine ourselves to the choice of subjects, in which poetry, like painting, having no model in existence, can represent only statues.

But this discussion is foreign to the merit of Wincklemann: in the fine arts, he has shown us what constituted taste among the ancients; it was for the moderns, in this respect, to feel what it suited them to adopt or to reject. When a man of genius succeeds in displaying secrets of an antique or foreign nature, he renders service by the impulse which he traces: the motion thus received becomes part of ourselves; and the greater the truth that accompanies it, the less servile is the imitation it inspires.

Winckelmann has developed the true principles, now admitted into the arts, of the nature of the ideal; of that perfect nature, of which the type is in our imagination, and does not exist elsewhere. The application of these principles to literature is singularly productive.

The poetic of all the arts is united under the same point of view in the writings of Wincklemann, and all have gained by it. Poetry has been better comprehended by the aid of sculpture, and sculpture by that of poetry; and we have been led by the arts of Greece to her philosophy. Those metaphysics which have ideas for their object originate with the Germans , as they did formerly with the Greeks, in the adoration of supreme beauty, which our souls alone can conceive and acknowledge. This supreme ideal beauty is a reminiscence of heaven, our original country; the sculptures of Phidias, the tragedies of Sophocles, and the doctrines of Plato, all agree to give us the same notion of it under different forms.

Next … Madame de Staël on … Goethe

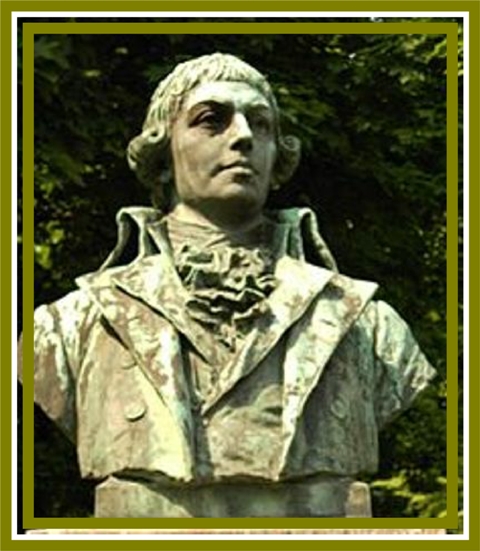

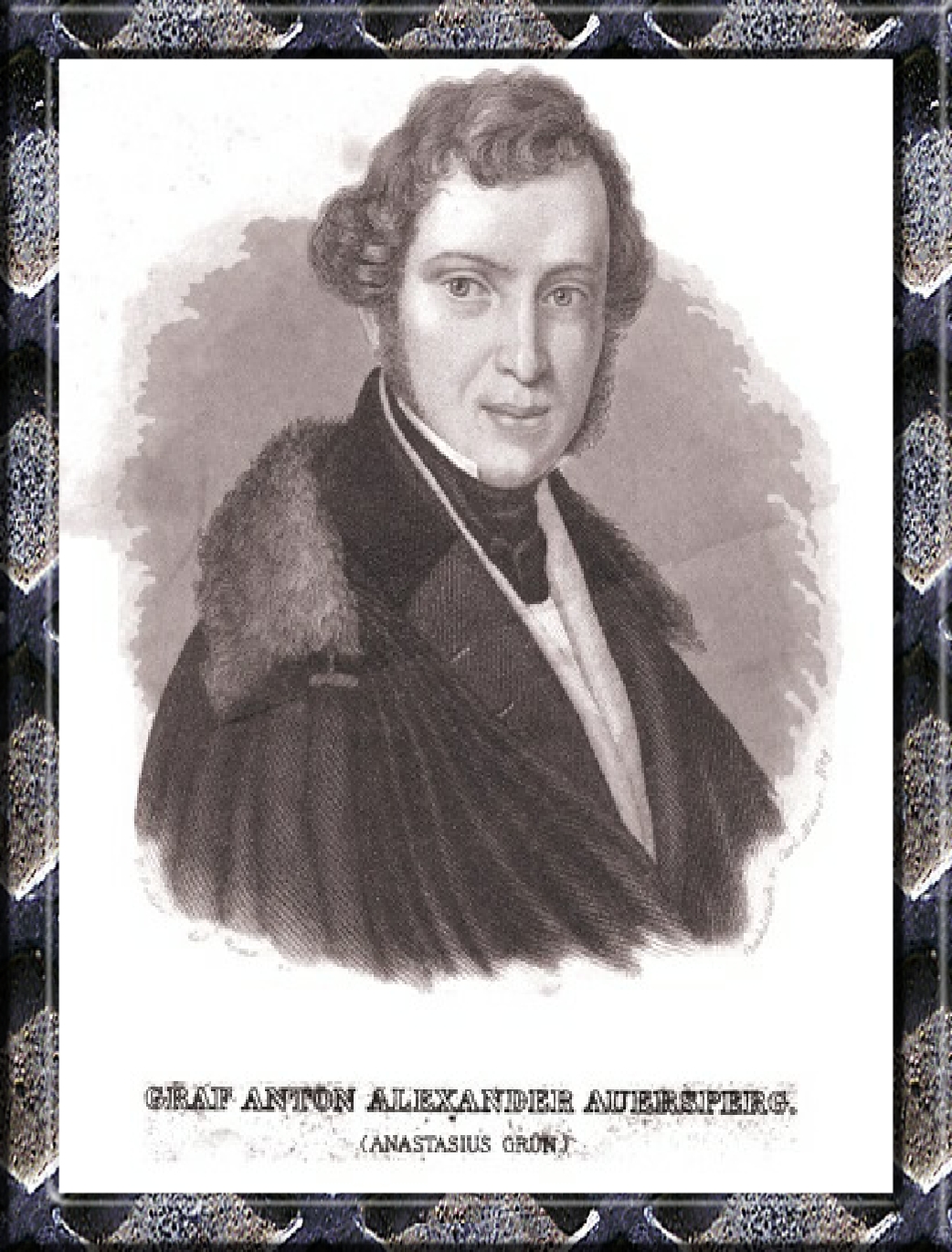

Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768)

by Raphael Mengs after 1755

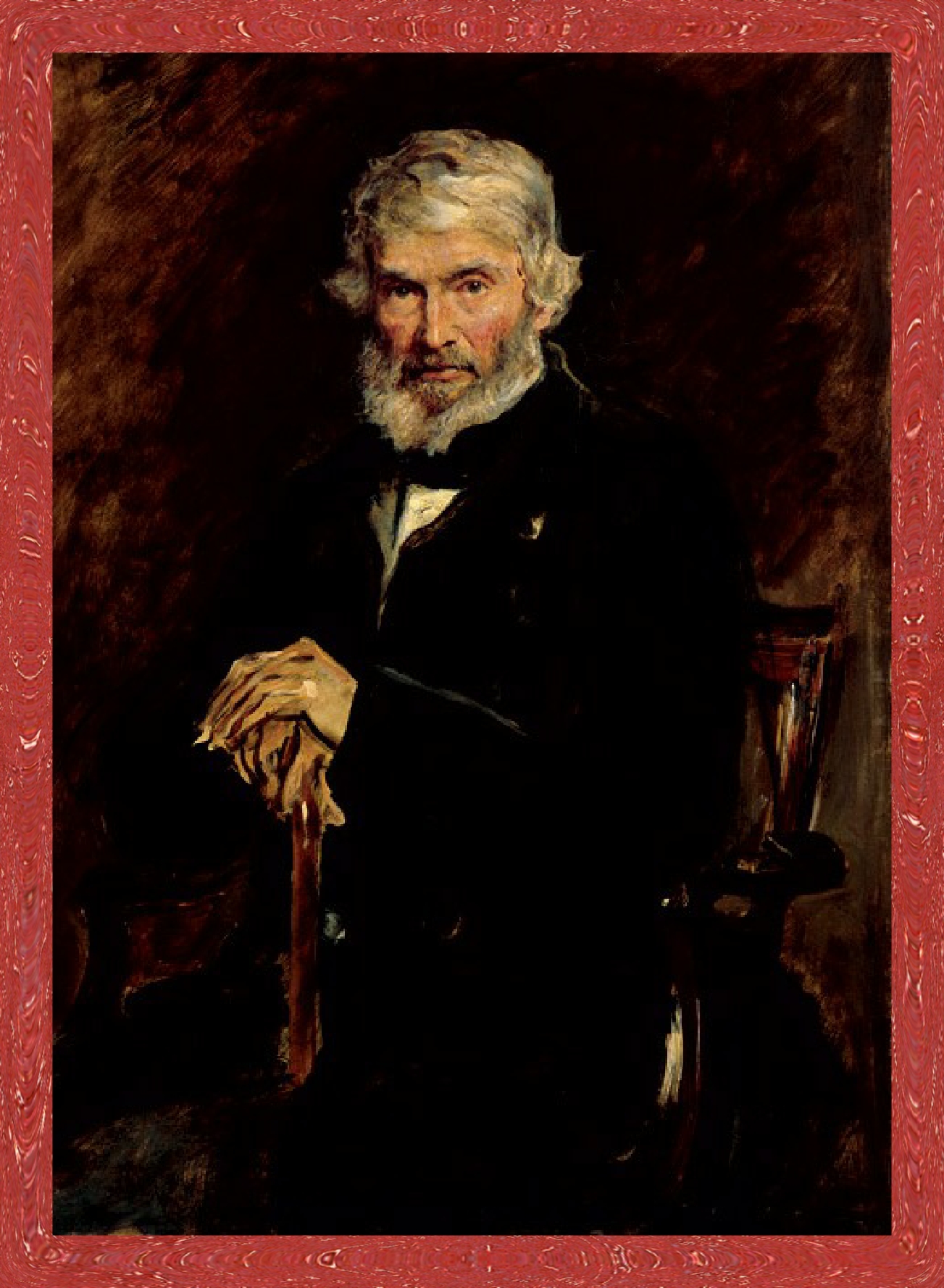

Madame de Staël: Lessing

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. I, 254-258

Perhaps the literature of Germany alone derived its source from criticism. In every other place criticism has followed the great productions of art; but in Germany it produced them. The epoch at which literature appears in its greatest splendour is the cause of this difference. Various nations had for many ages become illustrious in the art of writing: the Germans acquired it at a much later period, and thought they could do no better than follow the path already marked out. It was necessary then that criticism should expel imitation, in order to make room for originality.

Lessing wrote in prose with unexampled clearness and precision: depth of thought frequently embarrasses the style of the writers of the new school; Lessing, not less profound, had something severe in his character which made him discover the most concise and poignant modes of expression. Lessing was always animated in his writings by an emotion hostile to the opinion he attacked, and a sarcastic humour gives strength to his ideas.

He occupied himself by turns with the theatre, with philosophy, antiquities and theology, pursuing truth through all of them, like a huntsman, who feels more pleasure in the chase than in the attainment of his object. His style has, in some respects, the lively and brilliant conciseness of the French; and it conduced to render the German language classical. The writers of the new school embrace a great number of thoughts at the same time, but Lessing deserves to be more generally admired; he possesses a new and bold genius, which meets nevertheless the common comprehensions of mankind. His modes of perception are German, his manner of expression European.

Although a dialectician, at once lively and close in his arguments, enthusiasm for the beautiful filled his whole soul. He possessed ardour without glare, and a philosophical vehemence which was always active, and which by repeated strokes produced effect the most durable. Lessing analysed the French theatre, which was then fashionable in his country, and asserted that the English drama was more intimately connected with the genius of his countrymen.

In the judgment he passes on Merope, Zaire, Semiramus and Rodogune, he notices no particular improbability; he attacks the sincerity of the sentiments and characters, and finds fault with the personages of those fictions, as if they were real beings.

His criticism is a treatise on the human heart, as much as on poetical literature. To appreciate with justice the observations made by Lessing on the dramatic system in general, we must examine, as I mean to do in the following chapters, the principal differences of French and German on that subject. But in the history of literature, it is remarkable that a German should have had the courage to criticise a great French writer, and jest with wit on the very prince of jesters, Voltaire himself.

It was much for a nation lying under the weight of an anathema which refused it both taste and grace, to become sensible that in every country there exits a national taste, a national grace; and that literary fame may be acquired in various ways. The writings of Lessing gave a new impulse to his countrymen: they read Shakespeare, they dared in Germany to call themselves German; and the rights of originality were established instead of the yoke of correction.

Lessing has composed theatrical pieces and philosophical works which deserve to be examined separately: we should always consider German authors under various points of view. As they are still more distinguished by the faculty of thought than by genius, they do not devote themselves exclusively to any particular species of composition. Reflection attracts them successively to different modes of literature.

Amongst the writings of Lessing, one of the most remarkable is the Laocoon; it characterizes the subjects which are suitable both to poetry and painting, with as much philosophy in the principles as sagacity.

Tomorrow … Madame de Staël: Winckelmann

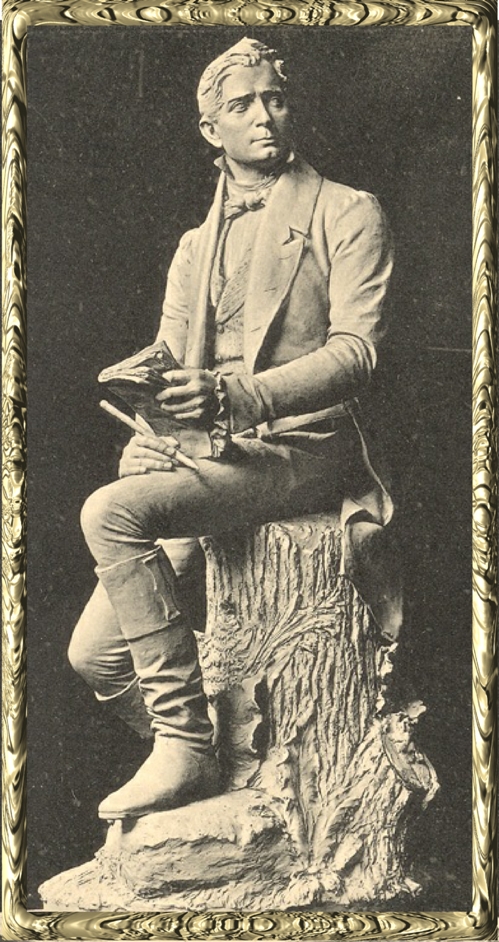

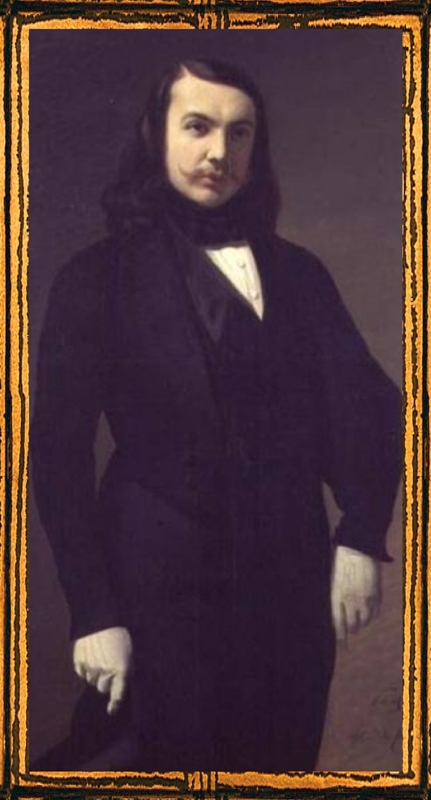

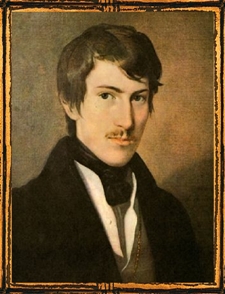

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing

1729-1781

Madame de Staël: Klopstock

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. I, 241-253

(Trans. note: The oak is the emblem of patriotic poetry, and the palm tree that of religious poetry, which comes from the east.)

In Germany, there have been many more remarkable men of the English than of the French school. Amongst the writers formed by English literature we must first reckon the admirable Haller, whose poetic genius served him so effectively, as a learned man, in inspiring him with the greatest enthusiasm for the beauties of nature, and the most extensive views of its various phenomena; Gessner, whose works are even more valued in France than in Germany; Gleim, Ramler, &c, and above them all, Klopstock.

His genius was inflamed by Milton and Young; but it was with him that the true German school first began. He expresses in a very happy manner in one of his odes the emulation of the Muses.

“I have seen — Oh, tell me! was it the present, or did I contemplate the future? I have seen the Muse of Germany enter the lists with the English Muse, and full of ardour press forward to victory.

Two goals, erected at the extremity of the course, were scarcely distinguishable: One was shaded by the oak, the other by palm trees.

Accustomed to such combats, the Muse of Albion proudly descended on the arena; she recollected the ground which she had already traversed in her sublime contest with the son of Meonides, with the lyrist of the Capitol. She saw her rival young and trembling, but her emotion was glorious: the ardour of victory flushed her countenance, and her golden hair flowed on her shoulders.

Scarcely retaining her respirations within her agitated bosom, already she thought she heard the trumpet; she devoured the arena with ardent eyes; she bent herself towards the goal.

Proud of such a rival, still more proud of herself, the noble English Muse measured the daughter of Tuisco with a glance. Yes, I remember, said she, in the forests of oak, near the ancient bards, together we sprung into birth.

But I was told that thou wert no more: Pardon, O Muse, if thou revivest to immortal life, pardon me that I knew it not till now. Nevertheless, I shall know it better when we arrive at the goal.

Is it there — dost thou see it in the distance? beyond that oak seest thou those palms, canst thou discern the crown? thou art silent — Oh! that proud silence, that constrained countenance, that look of fire fixed on the earth — I know it.

Nevertheless — think again before the dangerous signal, think — is it not I who maintained the contest with the Muse of Thermophyla, with her also of the seven hills?

She said: The decisive moment is arrived, the herald approaches: O daughter of Albion. cried the Muse of Germany, I love thee — but the palm of immortality is dearer to me even than thou art. Seize the crown if thy genius demands it, but let me be allowed to partake it with thee.

How my heart beats — immortal gods — even, if I were to arrive the first at the sublime object of our course — Oh! then thou wouldst follow close upon me — thy breath would agitate my flowing hair.

All at once the trumpet resounded; they fly with the rapidity of an eagle; a cloud of dust extends itself over the wide career: I saw them near the oak, but the cloud thickened, and they were soon lost to my sight.”

It is thus that the ode finishes, and there is a grace in not pointing out the victor.

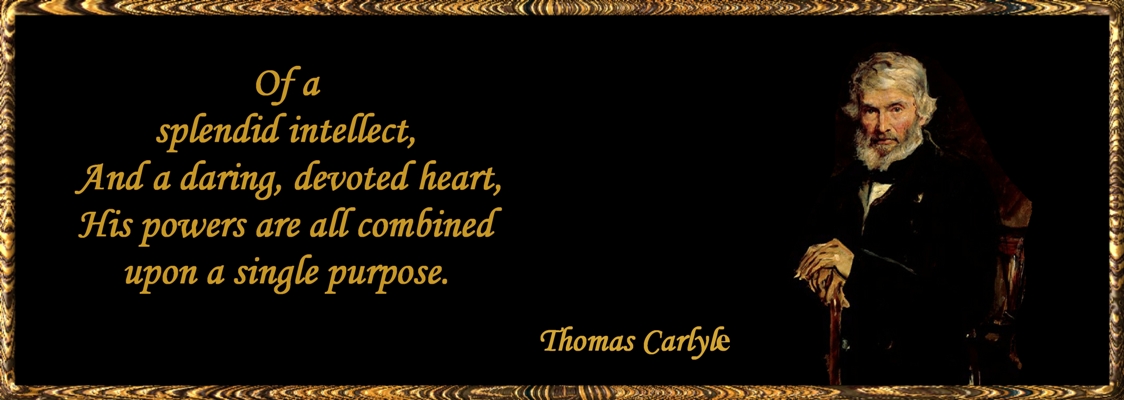

I refer the examination of Klopstock’s works in a literary point of view to the chapter on German poetry, and I now confine myself to the pointing them out as the actions of his life. The aim of all his works is either to awaken patriotism in his country, or to celebrate religion. If poetry had its saints, Klopstock would certainly be reckoned one of the first of them.

The greater part of his odes may be considered as Christian psalms; Klopstock is the David of the New Testament. But that which honours his character above all, without speaking of his genius, is a religious hymn under the form of an epic poem called the Messiah, to which he devoted twenty years. The Christian world already possessed two poems: The Inferno of Dante, and Milton’s Paradise Lost: One was full of images and phantoms, like the external religion of the Italians. Milton who had lived in the midst of Civil wars, above all excelled in the painting of his characters; and his Satan is a gigantic rebel armed against the monarchy of heaven.

Klopstock has conceived the Christian sentiment in all its purity; he consecrated his soul to the divine Saviour of men. The fathers of the church inspired Dante; the Bible inspired Milton. The greatest beauties of Klopstock’s poem are derived from the New Testament; from the divine simplicity of the gospel he knew how to draw a charming strain of poetry, which does not lessen its purity. In beginning this poem, it seems as if we were entering a great church, and that tender emotion, that devout meditation which inspires us in our Christian temples, also pervades the soul as we read the Messiah.

Klopstock, in his youth, proposed to himself this poem as the object and end of his existence. It appears to me that men would acquit themselves worthily with respect to this life, if a noble object, a grand idea of any sort, distinguished their passage through the world; and it is already an honourable proof of character to be able to direct towards one enterprize all the scattered rays of our faculties, the results of our labour. In whatever manner we judge of the beauties of our labour.

In whatever manner we judge of the beauties and defects of the Messiah, we ought frequently to read over some of its verses: the reading of the whole work may be wearisome, but ever time that we return to it, we breathe a sort of perfume of the soul, which makes us feel an attraction to all things holy and celestial.

After long labours, after a great number of years, Klopstock at length concluded his poem. Horace, Ovid, &c, have expressed in various manners the noble pride which seemed to ensure to them the immortal duration of their works.

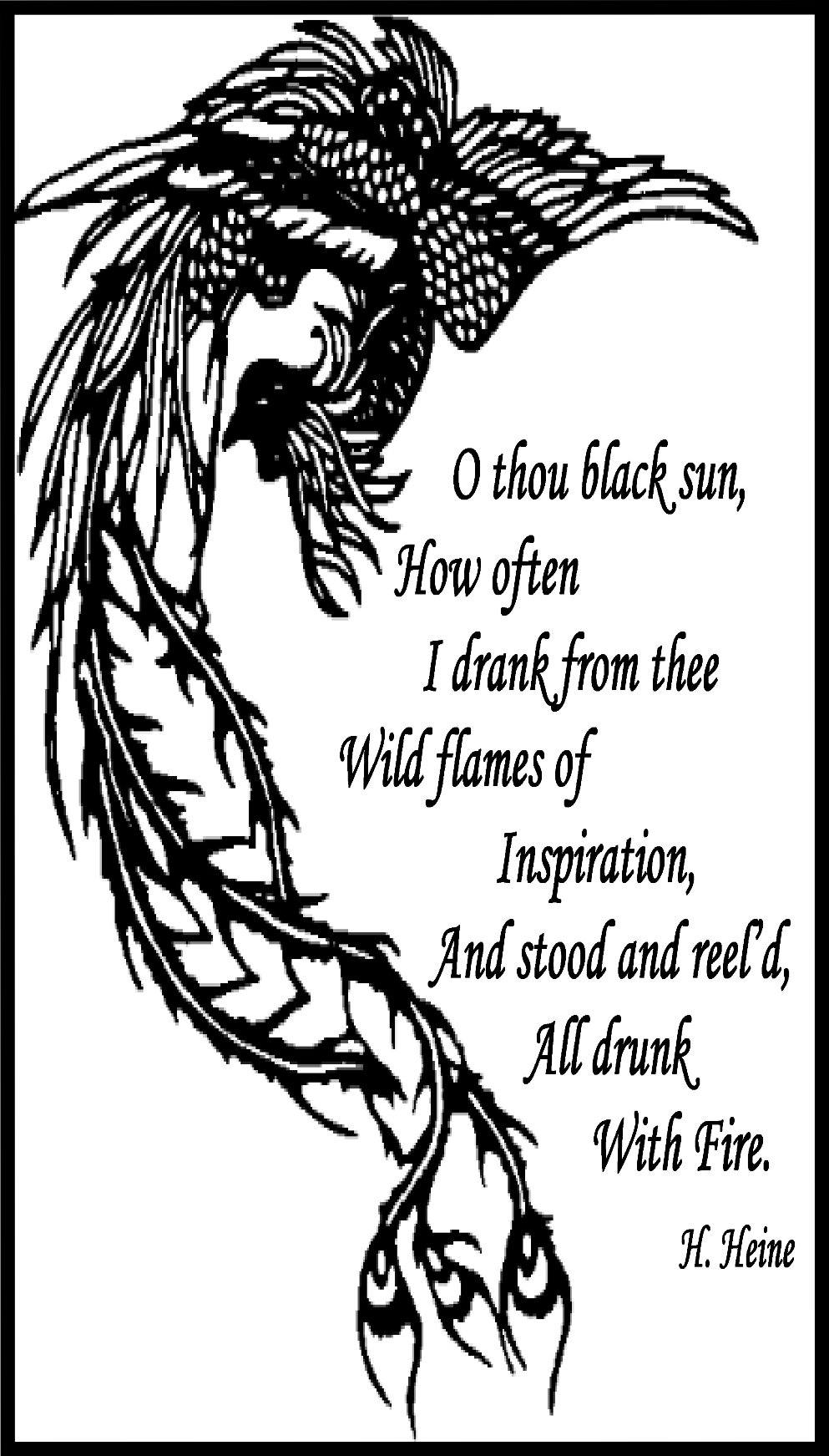

A sentiment of a very different nature penetrated the soul of Klopstock when his Messiah was finished. He expresses it thus in his Ode to the Redeemer, which is at the end of his poem.

“I have hoped in thee, O heavenly Mediator! I have sung the canticle of the new covenant: the formidable race is run, and thou hast pardoned my tottering footsteps.

Gratitude! eternal, ardent, exalted sentiment! O cause the harmony of my harp to resound. O, haste! my heart is overwhelmed with joy, and I shed tears of rapture.

I ask no recompense; have I not already tasted the pleasure of angels since I have sung the glories of my God? the emotion it occasioned penetrated to the inmost recesses of my soul, and it vibrated all that is most intimately connected with my being.

Heaven and earth disappeared from my sight; but soon the storm subsided: the breath of my life resembled the purse and sere air of a vernal day.

“Ah! am I not recompensed? have I not seen the tears of Christians flow? and in another world, perhaps, they will again welcome me with those holy tears! I have also felt terrestrial joy; my heart (in vain would I conceal it from thee), my heart was animated by ambition for glory: in my youth it palpitated with this sentiment; it still palpitates, but with a more chastened ardour.

“Has not thy apostle said to the faithful, ‘If there be any virtue, if there be any praise, think on those things!’ — It is this celestial flame which I have chosen for my guide; it appears before my steps, and displays a holier path to my ambitious site.

Led by this light, the delusion of terrestial pleasures has not deceived me. When I was in danger of wandering, the recollection of the holy hours in which my soul was initiated, the harmonious voices of angels, their harps, their concerts recalled me to myself.

I am at the goal, yes, I have reached it, and I tremble with happiness; thus (to speak in a human manner of celestial things), thus we shall be affected, when at a future day we shall find ourselves in the presence of Him who died and rose again for us.

It is my Lord and my God, whose powerful hand has led me to this goal through the graves which surrounded me; he armed me with strength and courage against approaching death; and dangers, unknown, but terrific, were warded from the poet who was thus protected by a celestial shield.

I have finished the song of the new covenant. I have traversed the formidable course. Oh heavenly Mediator, in thee have I put my trust.”

This mixture of poetic enthusiasm and religious confidence inspires both adminration and tenderness. Men of talents formerly addressed themselves to fabulous deities. Klopstock has consecrated his talents to God himself, and by the happy union of the Christian religion with poetry, he shews the Germans how possible it is to attain a property in the fine arts which may belong peculiarly to themselves, without being derived as servile imitations, from the ancients.

Those who have known Klopstock, respect as much as they admire him. Religion, liberty, love, occupied all his thoughts. His religious profession was found in the performance of all his duties: he even gave up the cause of liberty when innocent blood would have defiled it; and fidelity consecrated all the attachments of his heart. Never had he recourse to his imagination to justify an error; it exalted his soul without leading it astray. It is said that his conversation was full of wit and taste; that he loved the society of women, particularly of French women, and that he was a good judge of that sort of charm and grace which pedantry reproves.

I readily believe it; for there is always something of universality in genius, and perhaps it is connected by secret ties to grace, at least to that grace which is bestowed by nature.

How far distant is such a man from envy, selfishness, excess of vanity, which many writers have excused in themselves in the name of the talents they possessed! If they had possessed more, none of these defects would have agitated them. We are proud, irritable, astonished at our own perfections, when a little dexterity is mixed with the mediocrity of our character; but true genius inspires gratitude and modesty; for we feel from whom we received it, and we are also sensible of the limit, which he who bestowed has likewise assigned to it.

We find in the second part of the Messiah a very fine passage on the death of Mary, the sister of Martha and Lazarus, who is pointed out to us in the Gospel as the image of the contemplative virtue. Lazarus, who has received life a second time from Jesus Christ, bids his sister farewell with a mixture of grief and of confidence which is deeply affecting. From the last moments of Mary, Klopstock has drawn a picture of the death bed of the just. When in his turn he was also on his death bed, he repeated his verses on Mary with an expiring voice; he recollected them through the shades of the sepulchre, and in feeble accents he pronounced them as exhorting himself to die well: thus, the sentiments expressed in youth were sufficiently pure to form the consolation of his closing life.

Ah! how noble a gift is genius, when it has never been profaned, when it has been employed only in revealing to mankind under the attractive form of the fine arts, the generous sentiments and religious hopes which have before lain dormant in the human heart.

This same passage of the death of Mary was read with the burial service at Klopstock’s funeral. The poet was old when he ceased to live, but the virtuous man was already in possession of the immortal psalms which renew existence and flourish beyond the grave. All the inhabitants of Hamburgh rendered to the patriarch of literature the honours which elsewhere are scarcely ever accorded except to rank and power, and the manes of Klopstock received the reward which the excellence of his life had merited.

Tomorrow: Madame de Staël on Lessing

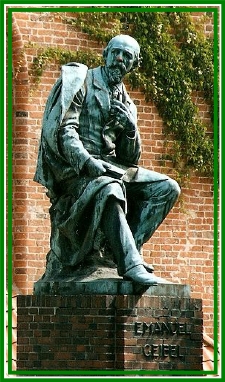

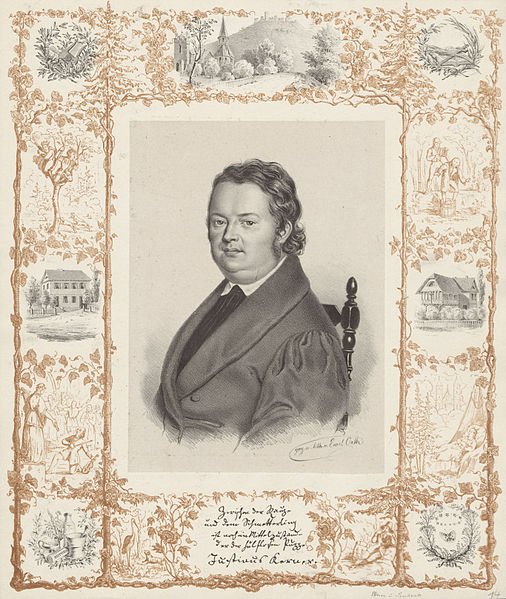

Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock (1724-1803)

by Johann Caspar Füssli (1750)

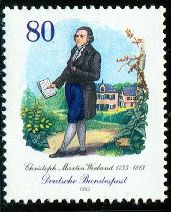

Madame de Staël: Weiland

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. I, 235-240

Of all the Germans who have written after the French manner, Wieland is the only one whose works have genius; and although he has almost always imitated the literature of foreign countries, we cannot avoid acknowledging the great services he has rendered to that of his own nation, by improving its language and giving it a versification more flowing and harmonious.

There was already in Germany a crowd of writers, who endeavored to follow the traces of French literature, such as it was in the age of Louis XIV.

Wieland is the first who introduced with success that of the 18th Century. In his prose writings he bears some resemblance to Voltaire, and in his poetry to Ariosto; but these resemblances, which are voluntary on his part, do not prevent him from being by nature completely German.

Weiland is infinitely better informed than Voltaire; he has studied the ancients with more erudition than has been done by any poet in France. Neither the defects, nor the powers of Weiland allow him to give to his writings any portion of the French lightness and grace.

In his philosophical novels, Agathon and Peregrinus Proteus, he begins very soon with analysis, discussion and metaphysics. He considers it as a duty to mix with them passages which we commonly call flowery; but we are sensible that his natural disposition would lead him to fathom all the depths of the subject which he endeavors to treat. In the novels of Weiland seriousness and gaiety are both too decidedly expressed ever to blend with each other; for in all things, though contrasts are striking, contrast extremes are wearisome.

In order to imitate Voltaire, it is necessary to possess a sarcastic and philosophical irony, which renders us careless of everything, except a poignant manner of expressing that irony. A German can never attain that brilliant freedom of pleasantry; he is too attached to truth, he wishes to know and to explain what things are, and even when he adopts reprehensible opinions, a secret repentance slackens his pace in spite of himself.

The Epicurean philosophy does not suit the German mind; they give to that philosophy a dogmatical character, while in reality it is seductive only when it presents itself under light and airy forms: As soon as you invest it with principles, it is equally displeasing to all.

The poetical works of Weiland have much more grace and originality than his prose writings. Oberon and the other poems of which I shall speak separately are charming and full of imagination. Weiland has, however, been reproached for treating the subject of love with too little severity, and he is naturally thus condemned by his own countrymen, who still respect women a little after the manner of their ancestors.

But whatever may have been the wanderings of imagination which Weiland allowed himself, we cannot avoid acknowledging in him a large portion of true sensibility; he has often had a good or bad intention of jesting on the subject of love; but his disposition, naturally serious, prevents him from giving himself boldly up to it. He resembles that prophet who found himself obliged to bless where he wished to curse; and he ends in tenderness what was begun in irony.

In our intercourse with Weiland we am charmed, precisely because his natural qualities are in opposition to his philosophy. This disagreement might be prejudicial to him as a writer, but it renders him more attractive in society; he is animated, enthusiastic, and, like all men of genius, still young even in his old age; yet he wishes to be skeptical, and is angry with those who would employ his fine imagination in the establishment of his faith.

Naturally benevolent, he is nevertheless susceptible of ill-humour; sometimes, because he is not pleased with himself, and sometimes, because he is not pleased with others. He is not pleased with himself, because he would willingly arrive at a degree of perfection in the manner of expressing his thoughts, of which neither words nor things are susceptible.

He does not choose to satisfy himself with those indefinite terms, which perhaps agree better with the art of conversation than perfection itself; he is sometimes displeased with others, because his doctrine, which is a little relaxed, and his sentiments, which are highly exalted, are not always easily reconciled.

He contains within himself the French poet and a German philosopher, who are alternately angry with each other; but this anger is still very easy to bear; and his discourse, filled with ideas and knowledge, might supply many men of talent with a foundation for conversation of many sorts.

The new writers, who have excluded all foreign influence from German literature, have been often unjust to Weiland. It is he whose works, even in translation, have excited the interest of all of Europe. It is he who has rendered the science of antiquity subservient to the charms of literature. It is he also who, in verse, has given a musical and graceful flexibility to his fertile but rough language.

It is, nevertheless, true, that his country would not be benefited by possessing many imitators of his writings; national originality is a much better thing; and we ought to wish, even when we acknowledge Weiland to be a good master, that he may have no disciples.

Tomorrow: Madame de Staël On Klopstock

Madame de Staël: Of the principal Epochs of German Literature

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. I, 228-234.

German Literature has never had what we are accustomed to call a golden age, that is to say, a period in which the progress of science is encouraged by the protection of a sovereign power. Leo X in Italy, Louis XIV in France, and in ancient times, Pericles and Augustus, have given their names to the age in which they lived. We may also consider the reign of Queen Anne as the most brilliant epoch of English literature; but this nation, which exists by its own powers, has never owed its great men to the influence of its kings. Germany was divided; in Austria no love of literature was discovered, and in Frederic II (who was all Prussia in himself alone), no interest whatever for German writers.

Literature, in Germany, has then never been concentrated to one point, and has never found support in the state. Perhaps it owes to this abandonment, as well as to the independence consequent on it, much of its originality and energy.

“We have seen poetry (says Schiller) despised by Frederic, the favoured son of his country, fly from the powerful throne which refused to protect it: but it still dared to call itself German; it felt proud in being itself the creator of its own glory. The songs of German bards resounded on the summits of the mountain, were precipitated as torrents into the vallies: the poet, independent, acknowledged no law, save the impression of his own soul, no sovereign but his own genius.”

It naturally followed from the want of encouragement given by government to men of literary talents in Germany that their attempts were made privately and individually in different directions, and that they arrived late at the truly remarkable period of their literature.

The German language, for a thousand years, was at first cultivated by monks, then by knights, and afterwards by artisans, such as Hans-Sachs, Sebastian Bran, and others, down to the period of the reformation; and latterly by learned men who have rendered it a language well adapted to all the subtleties of thought.

In examining the works of which German literature is composed, we find, according to the genius of the author, traces of these different modes of culture; as we see in mountains strata of the various minerals which the revolutions of the earth have deposited in them. The style changes its nature almost entirely, according to the writer; and it is necessary for foreigners to make a new study of every new book which they wish to understand.

The Germans, like the greater part of the nations in Europe in the times of chivalry, had also their troubadours and warriors, who sung of love and of battles. An epic poem has lately been discovered called the “Nibelungs” which was composed in the thirteenth century; we see in it the heroism and fidelity which distinguished the men of those times, when all was as true, strong and determinate, as the primitive colours of nature. The German in this poem is more clear and simple than it is at present; general ideas were not yet introduced into it, and traits of character only are narrated.

The German nation might then have been considered as the most warlike of all European nations, and its ancient traditions speak only of strong castles and beautiful mistresses, to whom they devoted their lives. When Maximilian endeavored at a later period to revive chivalry, the human mind no longer possessed that tendency; and those religious disputes had already commenced, which direct thought towards metaphysics, and place the strength of the soul rather in opinions than in actions.

Luther essentially improved his language by making it subservient to theological discussion; his translation of the Psalms and the Bible is still a fine specimen of it. The poetical truth and conciseness which he gives to his style are in all respect conformable to the genius of the German language, and even the sound of the words has an indescribable sort of energetic frankness on which we with confidence rely. The political and religious wars, which the Germans had the misfortune to wage with each other, withdrew the minds of men from literature, and when it was again resumed, it was under the auspices of the age of Louis XIV, at the period in which the desire of imitating the French pervaded almost all the courts and writers of Europe.

The works of Hagedorn, of Gellert, of Weiss, &c, were only heavy French, nothing original, nothing conformable to the natural genius of the nation. Those authors endeavored to attain French grace without being inspired with it, either by their habitrs, or their modes of life. They subjected themselves to rule, without having either the elegance or taste which may render even that despotism agreeable. Another school soon succeeded that of the French, and it was in Germanic Switzerland that it was erected. This school was at first founded on an imitation of English writers. Bodmer, supported by the example of the great Haller, endeavored to show that English literature agreed better with the German genius, than that of France.

Gottsched, a learned man without taste or genius, contested this opinion, and great light sprung from the dispute between these two schools. Some men then began to strike out a new road for themselves. Klopstock held the highest place in the English school, as Wieland did in that of the French; but Klopstock opened a new career for his succession, while Wieland was at once the first and the last of the French school in the eighteenth century. The first, because no other could equal him in that kind of writing, and the last, because after him the German writers pursued a path widely different.

As there still exist in all the Teutonic nations some sparks of that sacred fire which is again smothered by the ashes of time, Klopstock, at first imitating the English, succeeded at last in awakening the imagination and character peculiar to the Germans; and almost at the same moment, Winckelmann in the arts, Lessing in criticism, and Goethe in poetry, founded a true German school, if we may so call that, which admits of as many differences, as there are individuals, or varieties of talent.

I shall examine separately poetry, the dramatic arts, novels, and history; but every man of genius constituting (it may be said) a separate school in German, it appears to me necessary to begin by pointing out some of the principal traits which distinguish each writer individually, and by personally characterizing their most celebrated men of literature, before I set about analyzing their works.

Tomorrow: Madame de Staël: On Wieland.

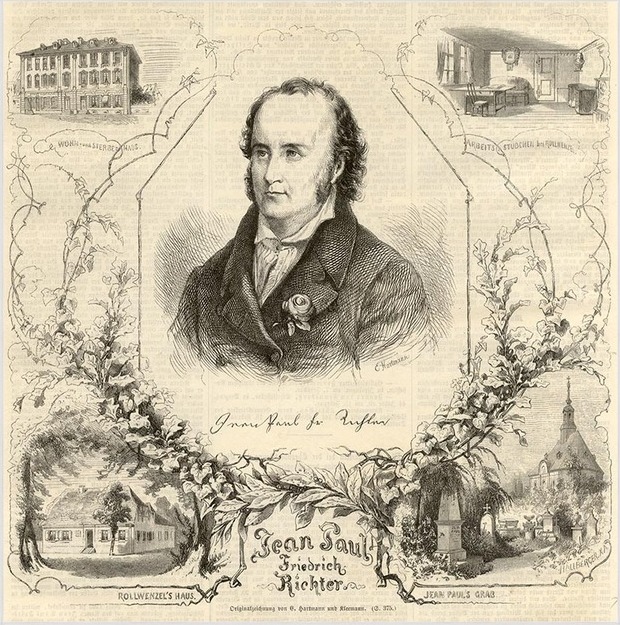

“Gunther Orders Hagen to Sink the Nibelung Treasure”

Peter Cornelius, 1859

The painting illustrates a scene from the 14th-century Middle High German saga, The Song of the Nibelungs [Nibelungenlied]. During the Napoleonic wars, the trappings of the Germanic medieval world – Gothic architecture, “old German” [altdeutsch] dress, northern tales and legends – came to embody the national longing for a unified German identity.

Therefore, it is not surprising that The Song of the Nibelungs, rediscovered in 1755 and praised by Goethe as worthy of a modern retelling, should have captured the imaginations of the Romantics. Such notable writers as Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué, Ludwig Tieck, and Friedrich Hebbel reworked the story in poetry, drama, and prose. New editions of the original poem were illustrated by Alfred Rethel, Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld, and Peter Cornelius (1824-1874). By mid-century, the saga had achieved the status of a national epic.

“For me, the hoard of the Nibelungs is a symbol of all German power, joy and majesty, all of which lies sunken in the Rhine and remains for the fatherland to win or lose,” Cornelius wrote in a letter in 1864. It’s most famous adaptation, of course, was Richard Wagner’s opera cycle, “The Ring of the Nibelungs,” which was composed between 1851 and 1874.”

http://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/about.cfm

Madame de Staël: On German Literature – The Schlegels

Part 2 of 2

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation).

After having done justice to the uncommon talents of the two Schlegels, we will now examine in what that partiality consists of which they are accused, and from which it is certain all their writings are not exempt. They are evidently prepossessed in favour of the Middle Ages and the opinions that were then prevalent; chivalry without spot, unbounded faith, and unstudied poetry, appear to them inseparable; and they apply themselves to all that may enable them to direct their minds and understandings of others to the same preference. W. Schlegel expresses his admiration for the Middle Ages in several of his writings, and particularly in two stanzas of which I now will give a translation.

“In those distinguished ages, Europe was sole and undivided, and the soil of that universal country was fruitful in those generous thoughts which are calculated to serve as guides through life and in death. Knighthood converted combatants into brethren in arms: they fought in defense of the same faith; the same love inspired all hearts, and the poetry which sung that alliance expressed the same sentiment in different languages.

Alas! the noble energy of ancient times is lost; our age is the inventor of a narrow-minded wisdom, and what weak men have no ability to conceive is in their eyes only a chimera; surely nothing truly great can succeed if undertaken with a groveling heart. Our times, alas! no longer know either faith or love; how then can hope be expected to remain with them.”

Opinions, whose tendency is so strongly marked, must necessarily affect impartiality of judgment on works of art. Without doubt, as I have continually repeated during the whole course of this work, it is much to be desired that modern literature should be founded on our history and our religion; it does not however follow that the literary productions of the Middle Ages should be considered as absolutely good. The energetic simplicity, the pure and loyal character which is displayed in them interests us warmly; but in the other hand, the knowledge of antiquity and the progress of civilization have given us advantages which are not to be despised. The object is not to trace back the arts to remote times, but to unite as much as we can all the various qualities which have been developed in the human mind at different periods.

The Schlegels have been strongly accused of not doing justice to French literature. There are, however, no writers who have spoken with more enthusiasm of the genius of our troubadours, and of the French chivalry which was unequaled in Europe, when it united in the highest degree, spirit and loyalty, grace and frankness, courage, and gaiety, the most affecting simplicity with the most ingenuous candor. But the German critics affirm that those distinguished traits of the French character were effaced during the course of the reign of Louis XIV. Literature, they say, in ages which are called classical, loses in originality what it gains in correctness. They have attacked our poets, particularly in various ways, and with great strength of argument. The general spirit of those critics is the same with that of Rousseau in his letter against French music. They think they discover in many of our tragedies that kind of pompous affectation, of which Rousseau accuses Lully and Rameau, and they affirm that the same taste which give the preference to Coypel and Boucher in painting, and to the Chevalier Bernini in sculpture, forbids in poetry that rapturous ardour which alone renders it a divine enjoyment; in short, they are tempted to apply to our manner of conceiving and of loving the fine arts the verses so frequently quoted from Corneille:

“Othon a la princesse a fait un compliment.

Plus en homme d’esprit qu’en veritable amant.”

W. Schlegel pays homage, however, to most of our great authors; but what he chiefly endeavors to prove is, that from the middle of the 17th Century, a constrained and affected manner has prevailed throughout Europe , and that this prevalence has made us lose those bold flights of genius which animated both writers and artists in the revival of literature. In the pictures and bas reliefs where Louis X!V is sometimes represented as Jupiter, and sometimes as Hercules, he is naked, or clothed only with the skin of a lion, but always with a great wig on his head. The writers of the new school tell us that this great wig may be applied to the physiognomy of the fine arts in the 17th Century: An affected sort of politeness, derived from factitious greatness, is always to be discovered in them.

It is interesting to examine the subject in this point of view, in spite of the innumerable objections which may be opposed to it. It is, however, certain that these German critics have succeeded in the object aimed at; as, of all writers since Lessing, they have most essentially contributed to discredit the imitation of French literature in Germany. But, from the fear of adopting French taste, they have not sufficiently improved that of their own country, and have often rejected just and striking observations, merely because they had before been made by our writers.

They know not how to make a book in Germany, and scarcely ever adopt that methodical order which classes ideas in the mind of the reader. It is not, therefore, because the French are impatient, but because their judgment is just and accurate, that this defect is so tiresome to them. In German poetry, fictions are not delineated with those strong and precise outlines which ensure the effect, and the uncertainty of the imagination corresponds to the obscurity of the thought. In short, if taste be found wanting in those strange and vulgar pleasantries which constitute what is called comic in some of their works, it is not because they are natural, but because the affectation of energy is at least as ridiculous as that of gracefulness. “I am making myself lively,” said a German as he jumped out a window. When we attempt to make ourselves anything, we are nothing. We should have recourse to the good taste of the French to secure us from the excessive exaggeration of some German authors, as on the other hand we should apply to the solidity and depth of the Germans to guard us from the dogmatic frivolity of some individuals amongst the men of literature of France.

Different nations ought to serve as guides to each other, and all would do wrong to deprive themselves of the information they may mutually receive and impart. There is something very singular in the difference which subsists between nations: the climate, the aspect of nature, the language, the government, and above all the events in history which have in themselves powers more extraordinary than all the others united. All combine to produce those diversities; and no man, however superior he may be, can guess at that which is naturally developed in the mind of him who inhabits another soil and breathes another air. We should do well then, in all foreign countries, to welcome foreign thoughts and foreign sentiments; for hospitality of that sort makes the fortune of him who exercises it.

Friedrich von Schlegel

Madame de Staël: On German Literature – The Schlegels

Part 1 of 2

“When I began the study of German literature, it seemed as if I was entering on a new sphere, where the most striking light was thrown on all that I had before perceived in the most confused manner.”

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation).

For some time past, little has been read in France except memoirs and novels, and it is not wholly from frivolity, that we are become less capable of more serious reading, but because the events of the revolution have accustomed us to value nothing but the knowledge of men and things. We find in German books, even on the most abstract subjects, that kind of interest which confers their value upon good novels, and which is excited by the knowledge which they teach us of our own hearts. The peculiar character of German literature is to refer everything to an interior existence; and as that is the mystery of mysteries, it awakens an unbounded curiosity.

I will say a few words on what may be considered as the legislation of that empire; I mean criticism. There is no branch of German literature which has been carried to a greater extent, and as in some cities there are more physicians than patients, there are sometimes in Germany more critics than authors. But the analyses of Lessing, who was the creator of style in German prose, are made in such a manner that they may themselves be thought of as works.

Kant, Goethe, J. de Mueller, the greatest German writers of every various kind, have inserted in periodicals of different publications recensions which contain the most profound philosophical theory and positive knowledge. Amongst the younger writers, Schiller and the two Schlegels have shown themselves superior…

The writings of A.W. Schlegel are less abstracted that those of Schiller; as his knowledge of literature is uncommon even in Germany, he is led continually to application by the pleasure which he finds in comparing different languages and different poems with each other; so general a point of view ought to be considered as infallible, if partiality did not sometimes impair it; but this partiality is not of an arbitrary kind, and I will point out both the progress and aim of it; nevertheless as there are subjects in which it is not perceived, it is of those I shall first speak.

W. Schlegel has given a course of dramatic literature in Vienna which comprises everything remarkable that has been composed for the theatre from the time of the Grecians to our days; it is not a barren nomenclature of the works of the various authors. He seizes the spirit of their different sorts of literature, with all the imagination of a poet; we are sensible that to produce such consequences extraordinary studies are required; but learning is not perceived in this work except by his perfect knowledge of the chefs d’oeuvre of composition. In a few pages we reap the labor of a whole life; every opinion formed by the author, every opinion, every epithet given to the writers of whom he speaks, is beautiful and just, concise and animated. W. Schlegel has found the art of treating the finest piece of poetry as so many wonders of nature, and of painting them in lively colors which do not injure the justness of the outline; for we cannot repeat too often that imagination, far from being an enemy to truth, brings it forward more than any other faculty of the mind, and all those who depend upon it as an excuse for indefinite terms or exaggerated expressions, are at least destitute of poetry as of good sense.

An analysis of the principles on which both tragedy and comedy are founded is treated in W. Schlegel’s course of dramatic literature with much depth of philosophy; this kind of merit is often found among the German writers. But Schlegel has no equal in the art of inspiring his own admiration; in general he shows himself attached to a simple taste, sometimes bordering on rusticity, but he deviates from his usual opinions in favor of the opinions of the inhabitants of the south. Their jeux de mots and their concetti are not the objects of his censure; he detests the affectation which owes its existence to the spirit of society, but that which is excited by the luxury of imagination pleases him in poetry as the profusion of colours and perfumes would do in nature. Schlegel, after having acquired a great reputation by his translation of Shakespeare, became equally enamored of Calderon, but with a very different sort of attachment that with which Shakespeare had inspired him; for while the English author is deep and gloomy in his knowledge of the human heart, the Spanish poet gives himself up with pleasure and delight to the beauty of life, to the sincerity of faith, and to all the brilliancy of those virtues which derive their coloring from the sunshine of the soul.

I was at Vienna when W. Schlegel gave his public course of lectures. I expected only good sense and instructions where the object was only to convey information; I was astonished to hear a critic as eloquent as an orator, and who, far from falling upon defects which are the eternal food of mean and little jealousy, sought only the means of reviving a creative genius.

Spanish literature is but little known, and it was the subject of one of the finest passages delivered during the setting at which I attended. W. Schlegel gave us a picture of the chivalrous nation, whose poets were all warriors, and whose warriors were poets. He mentioned that count Ercilla who composed his poem of the Araucana in a tent, as now on the shores of an ocean, now at the foot of the Cordilleras while he made war on those in revolt. Garcilasso, one of the descendants of the Incas, wrote poems on love on the ruins of Carthage, and perished at the siege of Tunis. Cervantes was dangerously wounded at the battle of Lepanto; Lope de Vega escaped by miracle at the defeat of the invincible armada; and Calderon served as an intrepid soldier in the wars of Flanders and Italy.