Category Archives: German Romanticism

Jean Paul’s “Death of an Angel”

Excerpt from “The Dream of the Lilybell, Tales and Poems; with translations of “Hymns to the Night” from the German of Novalis, and Jean Paul’s “Death of an Angel,”‘ by Henry Morley. 1845.

The Death of an Angel

As the Angel of the last hour, whom we so cruelly call Death, is sent to us the softest, kindest of the angels, that mildly and gently he may pluck from life the sinking heart of man, and bear it in warm hands, unhurt, from the cold breast to the high summery Eden. His brother is the Angel of the first hour, who twice kisses man, for the first time that his life here may be commenced, the second time that he may wake above without a wound; and enter smiling into the other world, as into this with tears.

When the battlefield stood full of blood and tears, and the Angel of the last hour drew from them trembling souls, his mild eye melted, and he said, “Alas! I also will die as a mortal, that I may learn what his last pangs are, and still them when I take his life away.” The unmeasured circle of the angels that love each other there above stood around the merciful Angel, and promised the beloved one that after the moment of death they would surround him with their beams, that he might know that it was Death had come; and his brother, whose kiss opens our rigid lips, as rays of morning the cold flowers, rested tenderly upon his breast and said, “When I kiss thee again, my brother, then art thou dead upon the earth, and once more ours.”

Full of emotion and love, the Angel sank down upon a battlefield where but one fair, fiery youth lay yet convulsed, and raised his shattered breast; the hero thought only of his betrothed, her hot tears that he could no longer feel, and her grief passed dimly over him as a distant battle cry. Oh, then, quickly the Angel covered him, and rested in the form of the loved one on his breast, and with a hot kiss drew the wounded soul out of his broken heart; and he gave the soul to his brother, and his brother kissed it in heaven the second time, and then it smiled already.

The Angel of the last hour entered as lightning into the deserted form, glowed through the corpse, and with the strengthened heart once more drove round the heated streams of life. But how was he affected by this new embodiment! His eye of light was dipped in the whirlpool of the new nervous spirit; his thoughts, once flying. waded wearily now through the misty circle of the brain. On all he saw the soft, moist halo of colors that hithereto had hung over every object with the autumn’s shades, was now dried up, and through the hot air things pierced him with their burning, paining color spots, every feeling became darker but nearer to himself, and seemed to him Instinct, as to us do those of brutes; hunger tore him, thirst burned him, pain cut him deeply. Oh, his distracted breast arose bleeding, and his first breath was his first sigh for the deserted heaven. “Is this the death of man?” he thought; but as he saw not the promised sign of death, no angel, and no glory-beaming heaven; he knew full well this was but man’s life.

At evening, the Angel’s earthly powers faded, and a crushing ball of earth seemed rolled upon his head, for Sleep had sent its messengers. The pictures in his soul left their sunshine for the light of a dull hazy fire; the shadows that the day had cast upon his brain, confused and colossal, moved through one another; and a spreading, unbounded world of fancy was cast over him; for the Dream sent its messengers. At length the shroud of sleep was wrapped in double folds around him, and, sunk into the grave of night, he lay there lonely and still, even as mortals. But then came’st thou on thy pinions, heavenly Dream, with thy thousand mirrors before his soul, and showed’st him in every mirror a circle of angels, and a heaven filled with their beams of glory; and the earthly body, with all its stings, seemed to fall from him. “Ah!” said he, in vane rapture, “my sleeping then was my departure!” But as he awoke again, his heart blocked up, and filled with heavy human blood, and he beheld the earth and the blood, he said, “That was not Death; it was Death’s picture only, although I saw the glorious heaven and the angels.”

The bride of the ascended hero observed not that in the breast of her beloved one only an angel dwelt; she still loved the erected temple of the departed soul, and still held joyfully the hand of him who was carried so far from her. But the Angel returned the love of her deluded heart with human love; jealous of her own proper form he wished not to die earlier than she, that he might love her all her lifetime, until one day in heaven she should forgive him the sin – that she had embraced upon the same breast an angel and a lover. But she died first – the early grief had bowed the flower’s head too low, and it remained on the grave. Oh, she sank before the weeping Angel, not as the sun that casts itself before admiring nature with magnificence into the sea, that its red waves may leap to heaven, but as the silent moon, that at midnight silvers a thin halo, and with that pale hero sinks unseen. Death sent before him his yet milder sister, Swoon; he touched the heart of the bride, and the warm face was frozen — the flowers on her cheeks closed up — the pale snow of winter , beneath which greens the spring of eternity, covered her brow, her hands.

Then burst the swelling eye of the Angel into a burning tear; and as he thought the heart freed itself with such a tear as with a pearl the sickly mussel; the bride moved her eyes, awakened to her last delusion, and drew him to her heart, and died as she kissed him. “Now am I with thee, my brother.” Then the Angel thought that his brother in heaven had given him the sign of the kiss of death; yet no beaming heaven was around, but the darkness of sorrow; and he sighed that that was not his death but only pangs of man for his companion.

“Oh, ye oppressed mortals,” exclaimed he, “ye weary ones, how can ye survive! Oh, how can ye grow old when the circle of youthful forms is broken, and at last is all destroyed when the graves of your friends descend as steps to your own graves, and when age is the silent empty evening hour of a cold battlefield! Oh, ye unhappy men, how can your hearts endure it!”

The body of the ascended hero exposed the mild angel to the cruelties of men; to his injustice, to the gnawings of sin and sorrow; along his form also was laid the stinging girdles of united septres, that presses land in agony, and which the great of the earth draw ever yet more closely; he saw the claws of crowned heraldic beasts fixed in the featherless prey, and heard the victims flap their powerless wings; he saw the whole globe surrounded by interlacing, and black glittering rings of the giant serpent vice, that buries and hides within man’s breast its poisoned head. Ah! then must his soft heart that an eternity long had rested only on the warm angels full of love, be pierced by the hot sting of enmity, and the holy soul of love must tremble at a deep disunion. “Ah,” said he, “the death of man gives pain.” But this it was not, for no Angel had appeared.

Now he became in few days weary of a life that we endure for half a century, and longed for his return. The evening sun attracted his kindred soul. The splinters in his shattered breast wearied him with pain. He went, with the glow of evening on his pale cheeks, into the churchyard, the green garden of life, where the coverings of the fair souls he had unclothed were gathered together. With painful longing he stood upon the bare grave of the inexpressibly beloved departed bride, and looked upon the fading sun. Upon this loved hillock he looked down upon his aching body, and thought here also would’st thou rest, thou failing breast, here thou would’st smart no more, held I thee not erect. Then softly he thought over the heavy life of man, and the pain of his wound pointed out to him the pangs with which men buy their honor and their death, and which gladly he had spared the noble hero’s soul. Deeply was he moved by the excellence of man, and he wept for endless love towards men who, amid the crying of their own necessities, amid descended clouds and long mists upon the cutting path of life, turn not their eyes from the high star of duty, but spread out in the darkness their loving arms for each tortured bosom that may meet them, around whom glimmers naught but hope, to set in the old world, as the sun to rise upon the new.

Emotion opened then his wound, and the blood, the soul’s tears, flowed from his heart upon the beloved mound; the perishing body sank sweetly bleeding to death after the loved one; tears of joy broke up the falling sun into a rosy waving sea; distant echoes played through the liquid splendour as though earth fled away at a distance through the sounding ether. Then shot a dark cloud, or a little night, before the Angel, and was full of sleep, and now a heaven of glories was opened and shone over him, and a thousand angels flamed. “Art thou here once more, thou sportive Dream!” he said. But the Angel of the first hour came to him through the glory, and gave him the sign of the kiss, and said “That was Death, thou eternal brother, and heavenly friend.” And the youth and his beloved whispered it gently after him.

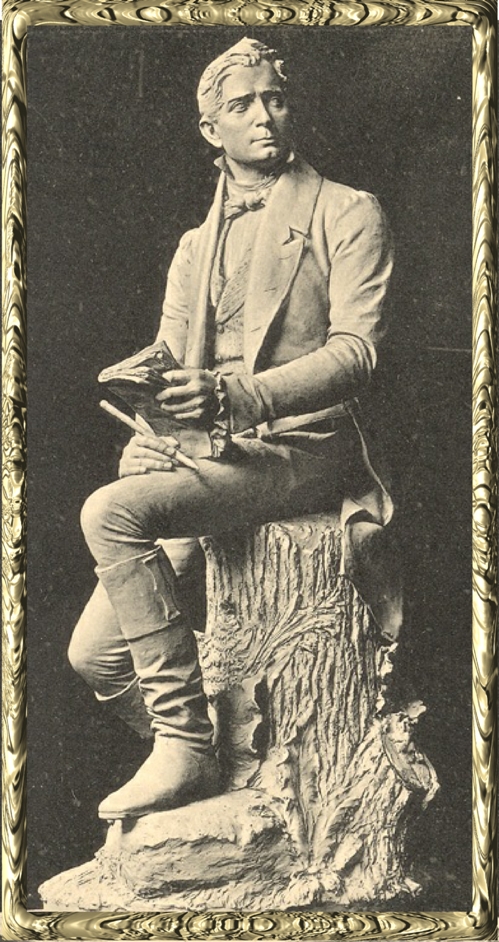

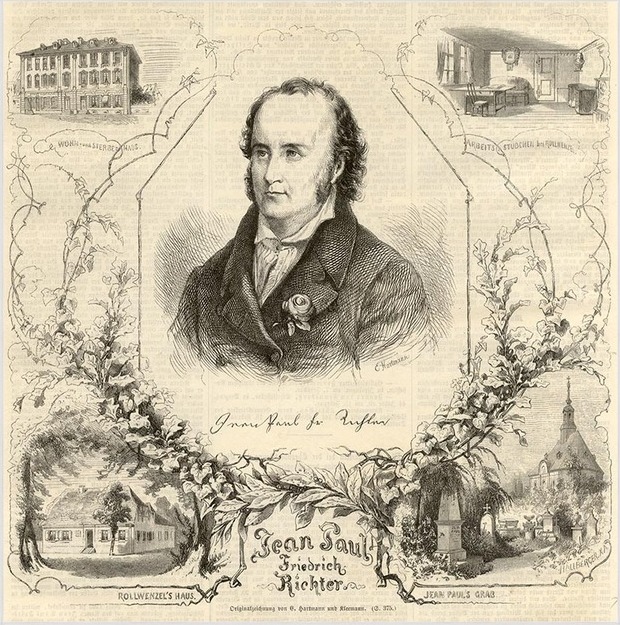

Jean Paul Friedrich Richter

Heinrich Heine: The Romantic School

The Poets of Legend: Goethe. Schiller and … Heinrich Heine.A favorite among Lieder composers, Heine’s literary works comprise twenty volumes, Die Romantische Schule two of them. Published in French and German 1833-36; this translation by Charles Godfrey Leland. Below, the great Poet’s thoughts on Novalis and Hoffmann.

But what was the Romantic School in Germany? It was nothing else but the Reawakening of the Middle Ages … its songs, images and architecture, in art and in life.

I have little to say regarding Schelling’s relationship to the Romantic School. His influence was mostly personal, but since the Philosophy of Nature through him has sprung into life and into vogue, Nature has been much more intelligently grasped by poets. Some are absorbed with all their human feelings into Nature; others have noted certain magic forms by means of which something human can be made to look forth and speak from it. The former are the true mystics, and resemble in many respects the Indian devotees who sink into Nature, and at last begin to feel in common with it. The others are more like enchanters, who, by their own power of will, evoked even fiends; they are like the Arabian sorcerers, who could animate every stone, or petrify, as they pleased, every living being.

To the first of these belong Novalis; to the second, Hoffmann.

Novalis saw everywhere the marvelous,

And, in its loveliness and beauty,

He listened to the language of the plants;

He knew the secret

Of every young rose, he identified himself with all

Nature; and when the autumn came and

the leaves fell, he died.

Hoffmann, on the contrary, saw spectres everywhere; they nodded to him from every Chinese teapot and every Berlin wig; he was a magician who changed men into brutes, and these again into Royal Prussian court counselors. He could call the dead from their graves, but he repulsed life from himself like a dismal ghost. And thus he felt he himself had become a spectre; all Nature was to him like a badly-ground mirror, in which he, distorted in a thousand ways, saw only his own death mask, and his works are only one terrible cry of agony in twenty volumes.

Hoffmann did not belong to the Romantic School. He was in no way allied to the Schlegels, and still less to their tendencies. I only mention him here in opposition to Novalis, who was really a poet of that kind. Novalis is less well known in France than Hoffmann, whom Loeve-Veimars has placed before the public in such admirable form, and thereby attained such a reputation.

By us inGermany, Hoffmann is no longer in fashion, but once it was otherwise. Once he was very much read, but only by men whose nerves were too strong or too weak to be affected by soft accords. Men of true genius and poetic natures would hear nothing of him; they, by far, preferred Novalis.

But, honestly speaking, Hoffmann was, as a poet. far superior to Novalis, for the latter always sweeps in the air with his ideal forms, while Hoffmann, with all his odd imps, sticks to earthly reality. But as the giant Antaeus remained invincibly strong while his feet touched his mother earth, and lost his strength when Hercules raised him in the air, so is the poet strong and powerful so long as he does not leave the basis of reality, but becomes weak when whirling about in the blue air.

The great resemblance in these poets lies in this: That in both their poetry is really a malady, and in this relation it has been declared that judgment as to their works was the business of a physician rather than a critic. The rosy gleam in the glow of Novalis is not the glow of health; and the purple heat in Hoffmann’s Phantasiestücken is not the flame of genius but of fever.

But have we the right to make such remarks, we who are not blessed with excess of health, above all at present; when literature resembles a vast lazar-house? Or is it perhaps poetry is a disease of mankind, just as the pearl is only the material of a disease which the poor oyster suffers?

Novalis was born May 2, 1772. His real name was Hardenberg. He loved a young lady who suffered from and died of consumption. This sad story inspired all his writings; his life was a dreamy dying in consequence, and he himself died of consumption in 1801, before he had completed his twenty-ninth year, or his novel.

This work as it exists is only the fragment of a great allegorical poem, which, like “Divine Comedy” of Dante, was to treat earnestly all things of earth and heaven. Heinrich von Ofterdingen, the famous poet, is the hero.

We see him as a youth in Eisenach, the charming town which lies at the foot of old Wartburg, where the greatest and also the stupidest things have been done; that is, where Luther translated the Bible, and certain idiotic Teutomaniacs burned the Gendarme Code of Herr Kamptz. There too in that castle was held the greatest contest of minstrels where among other poets Heinrich von Ofterdingen sang in the dangerous contest with Klingsohr of Hungary, an account of which has been preserved in the Manesse collection. He who was vanquished was to lose his head, and the Landgrave ofThuringia was to be the judge. The Wartburg rises as with mysterious signification over the cradle of the hero, and the beginning of the novel shows him in the paternal home of Eisenach.

The parents are still sleeping, the hanging clock beats monotonously, the wind blows against the rattling windows; now and then the room is lighted by the rays of the moon. The youth lays restlessly on the couch, thinking of the stranger and of his tales.

“It was not the treasure,” he said to himself, “which awoke in me such unutterable desire; all covetousness is far from me; but I long to see the Blue Flower. It haunts me all the time, and I can think and fancy of nothing else.”

Heinrich von Ofterdingen begins with such words, and the Blue Flower sheds it light and breathes its perfume through the whole romance. It is marvelous and full of meaning that the most imaginary characters of this book seem to us as real as if we had known them long ago.

Old memories awaken. The Muse of Novalis was a slender snow-white maid with serious blue eyes, golden hyacinthine locks and smiling lips … and I imagine it was the same damsel – the Muse of Novalis – who made me aware of him.

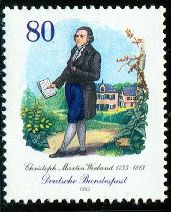

Novalis

Just a word…

Albrecht Adam – An Artist I Admire

Dear Readers,

I hope you enjoyed “The Castle of Scharfenstein” as much as I did.

How evocative the notion of a lone Rider’s venture into a dense ancient wood! How beguiling the tale of the dispossessed Prince.

I have many wonderful antique translations … and right now, a tale by E.T.A. Hoffmann called “Rolandsitten” has captured my fancy. But this, like many of the “shorter works” from my growing collection, is quite lengthy. (For example, Scharfenstein spanned 200 pages.)

Therein lies the challenge.

Because even if the scanning process produced a legible product, I dare not expose 150 to 200-year-old “spines” to such an ordeal. So, any stories I post here must come to you the old-fashioned way <g> by transcription.

But this, I will try to do about once a month.

Meanwhile, such excitement! A long-desired First Edition is finally on its way to me! “Specimens of German Romance, Selected and Translated from Various Authors.” George Soane, Translator.

Now this is an 1826 three-volume collection of five contemporary German tales, including “The Master Flea” by Hoffmann (Der Meister Floh), which is speculated to be its first appearance in English. George Soane was a prolific writer and translator, his most famous translation being La Motte-Fouque’s “Undine.” With frontispiece engravings by George Cruikshank, this present work was published the year beforeThomas Carlyle’s “German Romance: Specimens of its Chief Authors.” Apparently, the two translators were aware of each other’s endeavor, as neither duplicated the other.

Of particular note, Carlyle’s 1827 “German Romance” were my very first (and much prized!) antique volumes … and greatly influenced my passion for this unique literature. Now, I am thrilled that Soane’s “Specimens of German Romance” will soon be on my shelf as well.

You see, I createdPoets & Princesas my personal study guide … and a way to pursue this passion.

A Celebration of German Romantic Literature.

I am pleased to welcome you here.

Best regards,

Linda

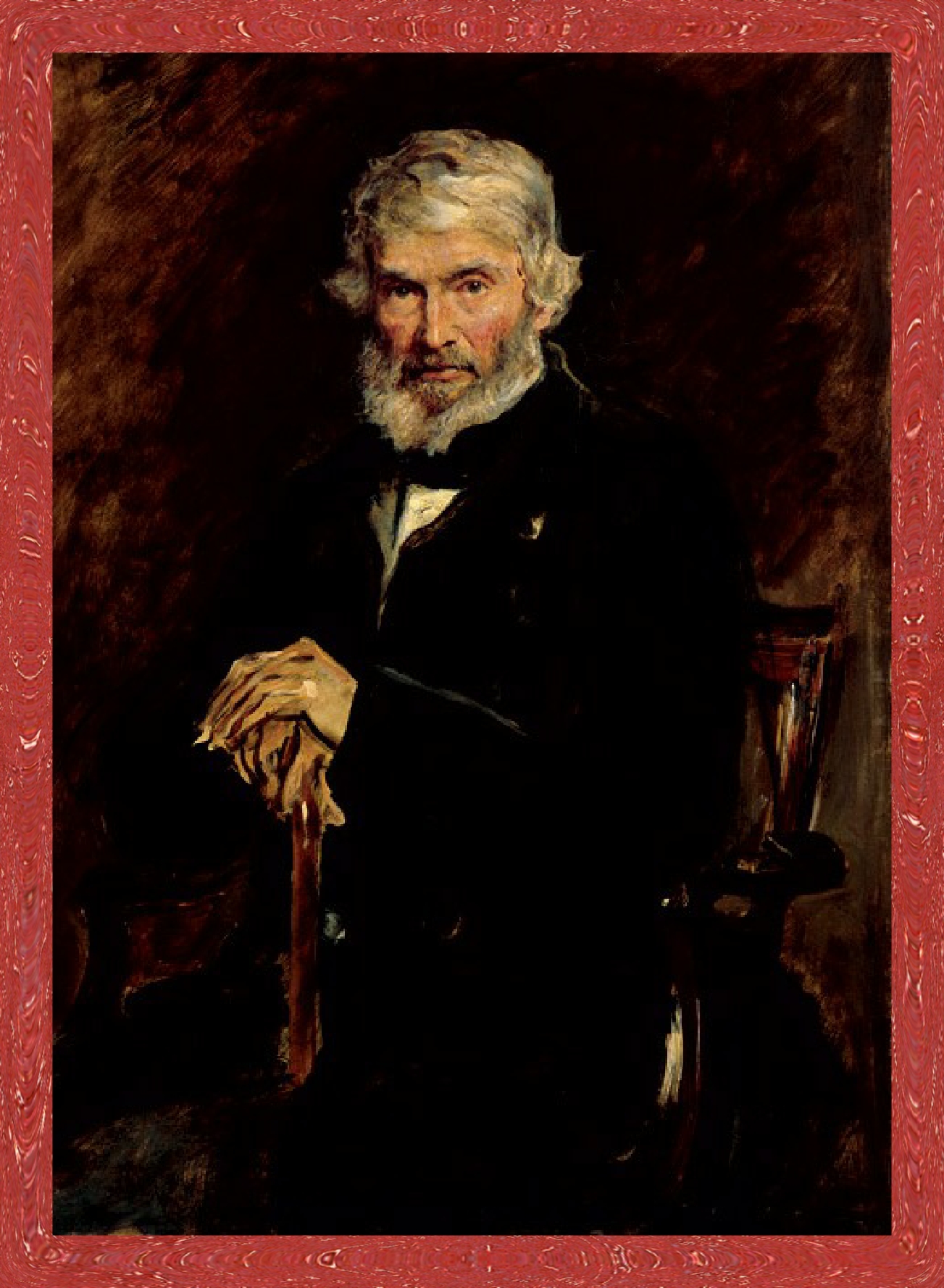

Thought once awakened does not again slumber.

Thomas Carlyle

.

.

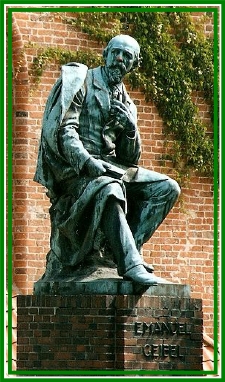

Thomas Carlyle: On Novalis 5/5

Excerpt: “Critical and Miscellaneous Essays: Novalis” by Thomas Carlyle, 1829.

What degree of critical satisfaction, what insight into the grand crisis of Novalis’s spiritual history, which seems to be here shadowed forth, our readers may derive from this Third Hymn to the Night, we shall not pretend to conjecture. Meanwhile, it were giving them a false impression of the Poet, did we leave him here; exhibited only under his more mystic aspects; as if his Poetry were exclusively a thing of Allegory, dwelling amid Darkness and Vacuity, far from all paths of ordinary mortals and their thoughts.

Novalis can write in the most common style, as well as in this most uncommon one; and there too not without originality. By far the greater part of his First Volume is occupied with a Romance, Heinrich von Ofterdingen, written, so far as it goes, much in the everyday manner; we have adverted the less to it, because we nowise reckoned it among his most remarkable compositions.

Like many of the others, it has been left as a Fragment; nay, from the account Tieck gives of its ulterior plan, and how from the solid prose world of the First part, this ‘Apotheosis of Poetry’ was to pass, in the Second, into a mythical, fairy and quite fantastic world, critics have doubted whether, strictly speaking, it could have been completed. From this work we select two passages, as specimens of Novalis’ manner in the more common style of composition; premising, which in this one instance we are entitled to do, that whatever excellence they may have will be universally appreciable.

The first is the introduction to the whole Narrative, as it were the text of the whole; the Blue Flower there spoken of being Poetry, the real object, passion and vocation of young Heinrich, which, through manifold adventures, exertions and sufferings, he is to seek and find. His history commences thus: ‘The old people were already asleep; the clock was beating its monotonous tick on the wall; the wind blustered over the rattling windows; by turns, the chamber was lighted by the sheen of the moon.

The young man lay restless in his bed; and thought of the stranger and his stories.

“It was not the treasure,” he said to himself, “which awoke in me such unutterable desire; all covetousness is far from me; but I long to see the Blue Flower. It haunts me all the time, and I can think and fancy of nothing else.”

Never did I feel so before: it is as if, till now, I had been dreaming, or as if sleep had carried me into another world; for in the world I used to live in, who troubled himself about flowers?

Such wild passion for a Flower was never heard of there. But whence could that stranger have come? None of us ever saw such a man; yet I know not how I alone was so caught with his discourse: the rest heard the very same, yet none seems to mind it. And then that I cannot even speak of my strange condition! I feel such rapturous contentment; and only then when I have not the Flower rightly before my eyes, does so deep, heartfelt an eagerness come over me; these things no one will or can believe.

I could fancy I were mad, if I did not see, did not think with such perfect clearness; since that day, all is far better known to me. I have heard tell of ancient times; how animals and trees and rocks used to speak with men. This is even my feeling: as if they were on the point of breaking out, and I could see in them, what they wished to say to me. There must be many a word which I know not; did I know more, I could better comprehend these matters. Once I liked dancing; now I had rather think to the music.” —

The young man lost himself, by degrees, in sweet fancies, and fell asleep. He dreamed first of immeasurable distances, and wild unknown regions. He wandered over seas with incredible speed; strange animals he saw; he lived with many varieties of men, now in war, in wild tumult, now in peaceful huts. He was taken captive and fell into the lowest wretchedness. All emotions rose to a height as yet unknown to him. He lived through an infinitely variegated life; died and came back; loved to the highest passion, and then again was forever parted from his loved one.

‘At length towards morning, as the dawn broke up without, his spirit also grew stiller, the images grew clearer and more permanent. It seemed to him he was walking alone in a dark wood. Only here and there did day glimmer through the green net. Ere long he came to a rocky chasm, which mounted upwards. He had to climb over many crags, which some former stream had rolled down. The higher he came, the lighter grew the wood.

At last he arrived at a little meadow, which lay on the declivity of the mountain. Beyond the meadow rose a high cliff, at the foot of which he observed an opening, that seemed to be the entrance of a passage hewn in the rock. The passage led him easily on, for some time, to a great subterranean expanse, out of which from afar a bright gleam was visible.

On entering, he perceived a strong beam of light, which sprang as if from a fountain to the roof of the cave, and sprayed itself into innumerable sparks, which collected below in a great basin: the beam glanced like kindled gold: not the faintest noise was to be heard, a sacred silence encircled the glorious sight. He approached the basin, which waved and quivered with infinite hues. The walls of the cave were coated with this fluid, which was not hot but cool, and on the walls threw out a faint bluish light. He dipt his hand in the basin, and wetted his lips.

It was as if the breath of a spirit went through him; and he felt himself in his inmost heart strengthened and refreshed. An irresistible desire seized him to bathe; he undressed himself and stept into the basin. He felt as if a sunset cloud were floating round him; a heavenly emotion streamed over his soul; in deep pleasure innumerable thoughts strove to blend within him; new, unseen images arose, which also melted together, and became visible beings around him; and every wave of that lovely element pressed itself on him like a soft bosom. The flood seemed a Spirit of Beauty, which from moment to moment was taking form round the youth.

“Intoxicated with rapture, and yet conscious of every impression, he floated softly down that glittering stream, which flowed out from the basin into the rocks. A sort of sweet slumber fell upon him, in which he dreamed indescribable adventures, and out of which a new light awoke him. He found himself on a soft sward at the margin of a spring, which welled out into the air, and seemed to dissipate itself there. Dark-blue rocks, with many-coloured veins, rose at some distance; the daylight which encircled him was clearer and milder than the common; the sky was black-blue, and altogether pure. But what attracted him infinitely most was a high, light-blue Flower, which stood close by the spring, touching it with its broad glittering leaves.

Round it stood innumerable flowers of all colours, and the sweetest perfume filled the air. he saw nothing but the Blue Flower and gazed on it long with nameless tenderness. At last he was for approaching, when all at once it began to move and change; the leaves grew more resplendent, and clasped themselves round the waxing stem; the Flower bent itself towards him; and the petals showed like a blue spreading ruff, in which hovered a lovely face. His sweet astonishment at this transformation was increasing, –when suddenly his mother’s voice awoke him, and he found himself in the house of his parents, which the morning sun was already gilding.’

Our next and last extract is likewise of a dream. Young Heinrich with his mother travels a long journey to see his grandfather at Augsburg; converses, on the way, with merchants, miners and red-cross warriors (for it is in the time of the Crusades); and soon after his arrival falls immeasurably in love with Matilda, the Poet Klingsohr’s daughter, whose face was that fairest one he had seen in his old vision of the Blue Flower.

Matilda, it would appear, is to be taken from him by death (as Sophie was from Novalis): meanwhile, dreading no such event, Heinrich abandons himself with full heart to his new emotions: ‘He went to the window. The choir of the Stars stood in the deep heaven; and in the east a white gleam announced the coming day.

‘Full of rapture, Heinrich exclaimed: “You, ye everlasting Stars, ye silent wanderers, I call you to witness my sacred oath. For Matilda will I live, and eternal faith shall unite my heart and hers. For me too the morn of an everlasting day is dawning. The night is by: to the rising Sun, I kindle myself as a sacrifice that never be extinguished.”

‘Heinrich was heated; and not till late, towards morning, did he fall asleep. In strange dreams the thoughts of his soul embodied themselves. A deep-blue river gleamed from the plain. On its smooth surface floated a bark; Matilda was sitting there, and steering. She was adorned with garlands; was singing a simple Song, and looking over to him with fond sadness. His bosom was full of anxiety. He knew not why. The sky was clear, the stream calm. Her heavenly countenance was mirrored in the waves. All at once the bark began to whirl. He called earnestly to her. She smiled and laid down her oar in the boat, which continued whirling.

An unspeakable terror took hold of him. He dashed into the stream; but he could not get forward; the water carried him. She beckoned, she seemed as if she wished to say something to him; the bark was filling with water; yet she smiled with unspeakable affection, and looked cheerfully into the vortex. All at once it drew her in. A faint breath rippled over the stream, which flowed on as calm and glittering as before. His horrid agony robbed him of consciousness. His heart ceased beating.

On returning to himself, he was again on dry land. It seemed as if he had floated far. It was a strange region. He knew not what had passed with him. His heart was gone. Unthinking he walked deeper into the country. He felt inexpressibly weary. A little well gushed from a hill; it sounded like perfect bells. With his hand he lifted some drops, and wetted his parched lips. Like a sick dream, lay the frightful event behind him. Farther and farther he walked; flowers and trees spoke to him. He felt so well, so at home in the scene. Then he heard that simple Song again. He ran after the sounds.

Suddenly some one held him by the clothes. “DearHenry,” cried a well-known voice. He looked round, and Matilda clasped him in her arms. “Why didst thou run from me, dear heart?” said she, breathing deep: “I could scarcely overtake thee.” Heinrich wept. He pressed her to him. “Where is the river?” cried he in tears. —

“Seest thou not its blue waves above us?” He looked up, and the blue river was flowing softly over their heads. “Where are we, dear Matilda?” –“With our Fathers.” –“Shall we stay together?” –“Forever,” answered she, pressing her lips to his, and so clasping him that she could not again quit hold. She put a wondrous secret Word in his mouth, and it pierced through all his being. He was about to repeat it, when his Grandfather called and he awoke. He would have given his life to remember that Word.’

This image of Death, and of the River being the Sky in that other and eternal country, seems to us a fine and touching one: there is in it a trace of that simple sublimity, that soft still pathos, which are characteristics of Novalis, and doubtless the highest of his specially poetic gifts.

But on these, and what other gifts and deficiencies pertain to him, we can no farther insist: for now, after such multifarious quotations, and more or less stinted commentaries, we must consider our little enterprise in respect of Novalis to have reached its limits; to be, if not completed, concluded. Our reader has heard him largely; on a great variety of topics, selected and exhibited here in such manner as seemed the fittest for our object, and with a true wish on our part, that what little judgment was in the mean while to be formed of such a man might be a fair and honest one.

Some of the passages we have translated will appear obscure; others, we hope, are not without symptoms of a wise and deep meaning; the rest may excite wonder, which wonder again it will depend on each reader for himself, whether he turn to right account or to wrong account, whether he entertain as the parent of Knowledge, or as the daughter of Ignorance. For the great body of readers, we are aware, there can be little profit in Novalis, who rather employs our time than helps us to kill it; for such any farther study of him would be unadvisable.

To others again, who prize Truth as the end of all reading, especially to that class who cultivate moral science as the development of purest and highest Truth, we can recommend the perusual and reperusal of Novalis with almost perfect confidence. If they feel, with us, that the most profitable employment any book can give them, is to study honestly some earnest, deep-minded, truth-loving Man, to work their way into his manner of thought, till they see the world with his eyes, feel as he felt and judge as he judged, neither believing nor denying, till they can in some measure so feel and judge, –then we may assert that few books known to us are more worth of their attention than this.

They will find it, if we mistake not, an unfathomed mine of philosophical ideas, where the keenest intellect may have occupation enough; and in such occupation, without looking farther, reward enough. All this, if the reader proceed on candid principles; if not it will be all otherwise. To no man, so much as to Novalis is that famous motto applicable:

Leser, wie gefall ich Dir?

Leser, wie gefullst Du mir?

Reader, how likest thou me?

Reader, how like I thee?For the rest, it were but a false proceeding did we attempt any formal character of Novalis in this place; did we pretend with such means as ours to reduce that extraordinary nature under common formularies; and in few words sum-up the net total of his worth and worthlessness. We have repeatedly expressed our own imperfect knowledge of the matter, and our entire despair of bringing even an approximate picture of it before readers so foreign to him.

The kind words, ‘amiable enthusiast,’ ‘poetic dreamer,’ or the unkind ones, ‘German mystic,’ ‘crackbrained rhapsodist,’ are easily spoken and written; but would avail little in this instance. If we are not altogether mistaken, Novalis cannot be ranged under any one of these noted categories; but belongs to a higher and much less known one, the significance of which is perhaps also worth studying, at all events will not till after long study become clear to us.

Meanwhile let the reader accept some vague impressions of ours on this subject, since we have no fixed judgment to offer him. We might say, that the chief excellence we have remarked in Novalis is his to us truly wonderful subtlety of intellect; his power of intense abstraction, of pursuing the deepest and most evanescent ideas through their thousand complexities, as it were, with lynx vision, and to the very limits of human Thought.

He was well skilled in mathematics, and, as we can easily believe, fond of that science; but his is a far finer species of endowment than any required in mathematics, where the mind, from the very beginning of Euclid to the end of Laplace, is assisted with visible symbols, with safe implements for thinking; nay, at least in what is called the higher mathematics, has often little more than a mechanical superintendence to exercise over these. This power of abstract meditation, when it is so sure and clear as we sometimes find it with Novalis, is a much higher and rarer one; its element is not mathematics, but that Mathesis, of which it has been said many a Great Calculist has not even a notion.

In this power, truly, so far as logical and not moral power is concerned, lies the summary of all Philosophic talent: which talent, accordingly, we imagine Novalis to have possessed in a very high degree; in a higher degree than almost any other modern writer we have met with.

His chief fault, again, figures itself to us as a certain undue softness, a want of rapid energy; something which we might term passiveness extending both over his mind and his character. There is a tenderness in Novalis, a purity, a clearness, almost as of a woman; but he has not, at least not at all in that degree, the emphasis and resolute force of a man. Thus, in his poetical delineations, as we complained above, he is too diluted and diffuse; not verbose properly; not so much abounding in superfluous words as in superfluous circumstances, which indeed is but a degree better.

In his philosophical speculations, we feel as if, under a different form, the same fault were not and then manifested. Here again, he seems to us, in one sense, too languid, too passive. He sits, we might say, among the rich, fine, thousandfold combinations, which his mind almost of itself presents him; but perhaps, he shows too little activity in the process, is too lax in separating the true from the doubtful, is not even at the trouble to express his truth with any laborious accuracy.

With his stillness, with his deep love of Nature, his mild, lofty, spiritual tone of contemplation, he comes before us in a sort of Asiatic character, almost like our ideal of some antique Gymnosophist, and with the weakness as well as the strength of an Oriental. However, it should be remembered that his works both poetical and philosophical, as we now see them, appear under many disadvantages; altogether immature, and not as doctrines and delineations, but as the rude draught of such; in which, had they been completed, much was to have changed its shape, and this fault, with many others, might have disappeared.

It may be, therefore, that this is only a superficial fault, or even only the appearance of a fault, and has its origin in these circumstances, and in our imperfect understanding of him. In personal and bodily habits, at least, Novalis appears to have been the opposite of inert; we hear expressly of his quickness and vehemence of movement.

In regard to the character of his genius, or rather perhaps of his literary significance, and the form under which he displayed his genius, Tieck thinks he may be likened to Dante. ‘For him’ says he, ‘it had become the most natural disposition to regard the commonest and nearest as a wonder, and the strange, the supernatural as something common; men’s every-day life itself lay round him like a wondrous fable, and those regions which the most dream of or doubt of as of a thing distant, incomprehensible, were for him a beloved home.

Thus did he, uncorrupted by examples, find out for himself a new method of delineation: and, in his multiplicity of meaning; in his view of Love, and his belief in Love, as at once his Instructor, his Wisdom, his Religion; in this, too, that a single grand incident of life, and one deep sorrow and bereavement grew to be the essence of his Poetry and Contemplation, –he, alone among the moderns, resembles the lofty Dante; and sings us, like him, an unfathomable mystic song, far different from that of many imitators, who think to put on mysticism and put it off, like a piece of dress.’

Considering the tendency of his poetic endeavors, as well as the general spirit of his philosophy, this flattering comparison may turn out to be better founded than at first sight it seems to be. Nevertheless, were we required to illustrate Novalis in this way, which at all times must be a very loose one, we should incline rather to call him the German Pascal than the German Dante. Between Pascal and Novalis, a lover of such analogies might trace not a few points of resemblance.

Both are of the purest, most affectionate moral nature; both of a high, fine, discursive intellect; both are mathematicians and naturalists, yet occupy themselves chiefly with Religion; nay, the best writings of both are left in the shape of ‘Thoughts,’ materials of a grand scheme, which each of them, with the views peculiar to his age, had planned, we may say, for the furtherance of Religion, and which neither of them lived to execute.

Nor in all this would it fail to be carefully remarked, that Novalis was not the French but the German Pascal; and from the intellectual habits of the one and the other, many national contrasts and conclusions might be drawn; which we leave to those that have a taste for such parallels.

We have thus endeavoured to communicate some views not of what is vulgarly called, but of what is a German Mystic; to afford English readers a few glimpses into his actual household establishment, and show them by their own inspection how he lives and works. We have done it, moreover, not in the style of derision, which would have been so easy, but in that of serious inquiry, which seemed so much more profitable. For this we anticipate not censure, but thanks from our readers. Mysticism, whatever it may be, should, like other actually existing things, be understood in well-informed minds.

We have observed, indeed, that the old-established laugh on this subject has been getting rather hollow of late; and seems as if erelong it would in a great measure die away. It appears to us that, in England there is a distinct spirit of tolerant and sober investigation abroad in regard to this and other kindred matters; a persuasion, fast spreading wider and wider, that the plummet of French or Scotch logic, excellent, nay, indispensable as it is for surveying all coasts and harbours, will absolutely not sound the deep-seas of human Inquiry; and that many a Voltaire and Hume, well-gifted and highly meritorious men, were far wrong in reckoning that when their six-hundred fathoms were out.

They had reached the bottom, which, as in the Atlantic, may lie unknown miles lower. Six-hundred fathoms is the longest, and a most valuable nautical line: but many men sound with six and fewer fathoms, and arrive at precisely the same conclusion.

‘The day will come,’ said Lichtenberg, in bitter irony, ‘when the belief in God will be like that in nursery Spectres’; or, as Jean Paul has it, ‘Of the World will be made a World-Machine, of the AEther a Gas, of God a Force, and of the Second-World — a Coffin.’ We rather think, such a day will not come. At all events, while the battle is still waging, and that Coffin-and-Gas philosophy has not yet secured itself with tithes and penal statutes, let there be free scope for Mysticism, or whatever else honestly opposes it. A fair field and no favour, and the right will prosper!

‘Our present time,’ says Jean Paul elsewhere, ‘is indeed a criticising and critical time, hovering betwixt the wish and the inability to believe; a chaos of conflicting times: but even a chaotic world must have its centre, and revolution round that centre; there is no pure entire Confusion, but all such presupposes its opposite, before it can begin.’

Novalis

Thomas Carlyle: On Novalis 4/5

Excerpt: “Critical and Miscellaneous Essays: Novalis” by Thomas Carlyle, 1829.

‘The Pupil,’ it is added, ‘listens with alarm to these conflicting voices.’ If such was the case in half-supernatural Sais, it may well be much more so in mere sublunary London. Here again, however, in regard to these vaporous lucubrations, we can only imitate Jean Paul’s Quintus Fixlein, who, it is said, in his elaborate Catalogue of German Errors of the Press, ‘states that important inferences are to be drawn from it, and advises the reader to draw them.’

Perhaps these wonderful paragraphs, which look, at this distance, so like chasms filled with mere sluggish mist, might prove valleys, with a clear stream and soft pastures, were we near at hand. For one thing, either Novalis, with Tieck and Schlegel at his back, are men in a state of derangement; or there is more in Heaven and Earth than has been dreamt of in our Philosophy. We may add that, in our view, this last Speaker, the ‘earnest Man,’ seems evidently to be Fichte; the first two Classses look like some sceptical or atheistic brood, unacquainted with Bacon’s Novum Organum, or having, the First class at least, almost no faith in it. That theory of the human species ending by a universal simultaneous act of Suicide, will, to the more simple sort of readers, be new.

As farther and more directly illustrating Novalis’ scientific views, we may here subjoin two short sketches, taken from another department of this Volume. To all who prosecute Philosophy, and take interest in its history and present aspects, they will not be without interest. The obscure parts of them are not perhaps unintelligible, but only obscure; which unluckily cannot, at all times, be helped in such cases: ‘Common Logic is the Grammar of the higher Speech, that is, of Thought; it examines merely the relations of ideas to one another, the Mechanics of Thought, the pure Physiology of ideas. Now logical ideas stand related to one another, like words without thoughts.

Logic occupies itself with the mere dead Body of the Science of Thinking. –Metaphysics, again, is the Dynamics of Thought; treats of the primary Powers of Thought; occupies itself with the mere Soul of the Science of Thinking. Metaphysical ideas stand related to one another, like thoughts without words. Men often wondered at the stubborn Incompletibility of these two Sciences; each followed its own business by itself; there was a want everywhere, nothing would suit rightly with either.

From the very first, attempts were made to unite them, as everything about them indicated relationship; but every attempt failed; the one or the other Science still suffered in these attempts, and lost its essential character. We had to abide by metaphysical Logic, and logical Metaphysic, but neither of them was as it should be. With Physiology and Psychology, with Mechanics and Chemistry, it fared no better. In the latter half of this Century there arose, with us Germans, a more violent commotion than ever; the hostile masses towered themselves up against each other more fiercely than heretofore; the fermentation was extreme; there followed powerful explosions.

And now some assert that a real Compenetration has somewhere or other taken place; that the germ of a union has arisen, which will grow by degrees, and assimilate all to one indivisible form: that this principle of Peace is pressing out irresistibly on all sides, and that erelong there will be but one Science and one Spirit, as one Prophet and one God.’–

‘The rude, discursive Thinker is the Scholastic (Schoolman Logician). The true Scholastic is a mystical Subtlist; out of logical Atoms he builds his Universe; he annihilates all living Nature, to put an Artifice of Thoughts (Gedankenkunststuck, literally Conjuror’s-trick of Thoughts) in its room. His aim is an infinite Automaton. Opposite to him is the rude, intuitive Poet: this is a mystical Macrologist: he hates rules and fixed form; a wild, violent life reigns instead of it in Nature; all is animate, no law; wilfulness and wonder everywhere. He is merely dynamical.

Thus does the Philosophic Spirit arise at first, in altogether separate masses. In the second stage of culture these masses begin to come in contact, multifariously enough; and, as in the union of infinite Extremes, the Finite, the Limited arises, so here also arise “Eclectic Philosophers” without number; the time of misunderstanding begins. The most limited is, in this stage, the most important, the purest Philosopher of the second stage. This class occupies itself wholly with the actual, present world, in the strictest sense.

The Philosophers of the first class look down with contempt on those of the second; say, they are a little of everything, and so nothing; hold their views as the results of weakness, as Inconsequentism. On the contrary, the second class, in their turn, pity the first; lay the blame on their visionary enthusiasm, which they say is absurd, even to insanity.

‘If on the one hand the Scholastics and Alchemists seem to be utterly at variance, and the Eclectics on the other hand quite at one, yet, strictly examined, it is altogether the reverse. The former, in essentials, are indirectly of one opinion; namely, as regards the non-dependence, and infinite character of Meditation, they both set out from the Absolute: whilst the Eclectic and limited sort are essentially at variance; and agree only in what is deduced. The former are infinite but uniform, the latter bounded but multiform; the former have genius, the latter talent; those have Ideas, these have knacks (Handgriffe); those are heads without hands, these are hands without heads.

The third stage is for the Artist, who can be at once implement and genius. He finds that that primitive Separation in the absolute Philosophical Activities’ (between the Scholastic, and the “rude, intuitive Poet”) ‘is a deeper-lying Separation in his own Nature; which Separation indicates, by its existence as such, the possibility of being adjusted, of being joined: he finds that, heterogeneous as these Activities are, there is yet a faculty in him of passing from the one to the other, of changing his polarity at will.

He discovers in them, therefore, necessary members of his spirit; he observes that both must be united in some common Principle. He infers that Eclecticism is nothing but the imperfect defective employment of this principle. It becomes —‘

–But we need not struggle farther, wringing a significance out of these mysterious words: in delineating the genuine Transcendentalist, or ‘Philosopher of the third state,’ properly speaking the Philosopher, Novalis ascends into regions whither few readers would follow him. It may be observed here that British Philosophy, tracing it from Duns Scotus to Dugald Stewart, has now gone through the first and second of these ‘stages,’ the Scholastic and the Eclectic, and in considerable honour. With our amiable Professor Stewart, than whom no man, not Cicero himself, was ever more entirely Eclectic, that second or Eclectic class may be considered as having terminated; and now Philosophy is at a stand among us, or rather there is now no Philosophy visible in these Islands.

It remains to be seen, whether we also are to have our ‘third stage’; and how that new and highest ‘class’ will demean itself here. The French Philosophers seem busy studying Kant, and writing of him: but we rather imagine Novalis would pronounce them still only in the Eclectic stage. He says afterwards, that ‘all Eclectics are essentially and at bottom sceptics; the more comprehensive, the more sceptical.’

These two passages have been extracted from a large series of Fragments, which, under the three divisions of Philosophical, Critical, Moral, occupy the greatest part of Volume Second. They are fractions, as we hinted above, of that grand ‘encyclopedical work’ which Novalis had planned. Friedrich Schlegel is said to be the selector of those published here. They come before us without note or comment; worded for the most part in very unusual phraseology; and without repeated and most patient investigation, seldom yield any significance, or rather we should say, often yield a false one.

A few of the clearest we have selected for insertion: whether the reader will think them ‘Pollen of Flowers,’ or a baser kind of dust, we shall not predict. We give them in a miscellaneous shape; overlooking those classifications which, even in the text, are not and could not be very rigidly adhered to.

‘Philosophy can bake no bread; but she can procure for us God, Freedom, Immortality. Which, then, is more practical, Philosophy or Economy?–

‘Philosophy is properly Home-sickness; the wish to be everywhere at home.–

‘We are near awakening when we dream that we dream.–

‘The true philosophical Act is annihilation of self (Selbsttodtung); this is the real beginning of all Philosophy; all requisites for being a Disciple of Philosophy point hither. This Act alone corresponds to all the conditions and characteristics of transcendental conduct.–

‘To become properly acquainted with a truth, we must first have disbelieved it, and disputed against it.–

‘Man is the higher Sense of our Planet; the star which connects it with the upper world; the eye which it turns towards Heaven.–

‘Life is a disease of the spirit; a working incited by Passion. Rest is peculiar to the spirit.–

‘Our life is no Dream, but it may and will perhaps become one.–

‘What is Nature? An encyclopedical, systematic Index or Plan of our Spirit. Why will we content us with the mere catalogue of our Treasures? Let us contemplate them ourselves, and in all ways elaborate and use them.–

‘If our Bodily Life is a burning, our Spiritual Life is a being burnt, a Combustion (or, is precisely the inverse the case?); Death, therefore, perhaps a Change of Capacity.–

‘Sleep is for the inhabitants of Planets only. In another time, Man will sleep and wake continually at once. The greater part of our Body, of our Humanity itself, yet sleeps a deep sleep.–

‘There is but one Temple in the World; and that is the Body of Man. Nothing is holier than this high form. Bending before men is a reverence done to this Revelation in the Flesh. We touch Heaven, when we lay our hand on a human body.–

‘Man is a Sun; his Senses are the Planets.–

‘Man has ever expressed some symbolical Philosophy of his Being in his Works and Conduct; he announces himself and his Gospel of Nature; he is the Messiah of Nature.–

‘Plants are Children of the Earth; we are Children of the AEther. Our Lungs are properly our Root; we live, when we breathe; we begin our life with breathing.–

‘Nature is an AEolian Harp, a musical instrument; whose tones again are keys to higher strings in us.–

‘Every beloved object is the centre of a Paradise.–

‘The first Man is the first Spirit-seer; all appears to him as Spirit. What are children, but first men? The fresh gaze of the Child is richer in significance than the forecasting of the most indubitable Seer.–

‘It depends only on the weakness of our organs and of our self-excitement (Selbstberuhrung), that we do not see ourselves in a Fairy-world. All Fabulous Tales (Mahrchen) are merely dreams of that home world, which is everywhere and nowhere. The higher powers in us, which one day as Genies, shall fulfil our will, are, for the present, Muses, which refresh us on our toilsome course with sweet remembrances.–‘

(*1*) Novalis’s ideas, on what has been called the ‘perfectibility of man,’ ground themselves on his peculiar views of the constitution of material and spiritual Nature, and are of the most original and extraordinary character.

With our utmost effort, we should despair of communicating other than a quite false notion of them. He asks, for instance, with scientific gravity: Whether any one, that recollects the first kind glance of her he loved, can doubt the possibility of Magic?

‘Man consists in Truth. If he exposes Truth, he exposes himself. If he betrays Truth, he betrays himself. We speak not here of lies, but of acting against Conviction.–

‘A character is a completely fashioned will (vollkommen gebildeter Wille).–

‘There is, properly speaking, no Misfortune in the world. Happiness and Misfortune stand in continual balance. Every Misfortune is, as it were, the obstruction of a stream, which, after overcoming this obstruction, but bursts through with the greater force.–

‘The ideal of Morality has no more dangerous rival than the ideal of highest Strength, of most powerful life; which also has been named (very falsely as it was there meant) the ideal of poetic greatness. It is the maximum of the savage; and has, in these times, gained, precisely among the greatest weaklings, very many proselytes. By this ideal, man becomes a Beast-Spirit, a Mixture; whose brutal wit has, for weaklings, a brutal power of attraction.–

‘The spirit of Poesy is the morning light, which makes the Statue of Memnon sound.–

‘The division of Philosopher and Poet is only apparent, and to the disadvantage of both. It is a sign of disease, and of a sickly constitution.–

‘The true Poet is all-knowing; he is an actual world in miniature.–

‘Klopstock’s works appear, for the most part, free Translations of an unknown Poet, by a very talented but unpoetical Philologist.–

‘Goethe is an altogether practical Poet. He is in his works what the English are in their wares: highly simple, neat, convenient and durable. He has done in German Literature what Wedgwood did in English Manufacture. He has, like the English, a natural turn for Economy, and a noble Taste acquired by Understanding. Both these are very compatible, and have a near affinity in the chemical sense. * * —Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship may be called throughout prosaic and modern. The Romantic sinks to ruin, the Poesy of Nature, the Wonderful. The Book treats merely of common worldly things: Nature and Mysticism are altogether forgotten.

It is a poetised civic and household History; the Marvellous is expressly treated therein as imagination and enthusiasm. Artistic Atheism is the spirit of the Book. * * * It is properly a Candide, directed against Poetry: the Book is highly unpoetical in respect of spirit, poetical as the dress and body of it are. * * * The introduction of Shakspeare has almost a tragic effect. The hero retards the triumph of the Gospel of Economy; and economical Nature is finally the true and only remaining one.–

‘When we speak of the aim and Art observable in Shakspeare’s works, we must not forget that Art belongs to Nature; that it is, so to speak, self-viewing, self-imitating, self-fashioning Nature. The Art of a well-developed genius is far different from the Artfulness of the Understanding, of the merely reasoning mind. Shakspeare was no calculator, no learned thinker; he was a mighty, many-gifted soul, whose feelings and works, like products of Nature, bear the stamp of the same spirit; and in which the last and deepest of observers will still find new harmonies with the infinite structure of the Universe; concurrences with later ideas, affinities with the higher powers and senses of man.

They are emblematic, have many meanings, are simple and inexhaustible, like products of Nature; and nothing more unsuitable could be said of them than that they are works of Art, in that narrow mechanical acceptation of the word.’

The reader understands that we offe these specimens not as the best to be found in Novalis’s Fragments, but simply as the most intelligible. Far stranger and deeper things there are, could we hope to make them in the smallest degree understood. But in examining and reexamining many of his Fragments, we find ourselves carried into more complex, more subtle regions of thought than any we are elsewhere acquainted with: here we cannot always find our own latitude and longitude, sometimes not even approximate to finding them; much less teach others such a secret.

What has been already quoted may afford some knowledge of Novalis, in the characters of Philosopher and Critic: there is one other aspect under which it would be still more curious to view and exhibit him, but still more difficult, –we mean that of his Religion. Novalis nowhere specially records his creed, in these Writings: he many times expresses, or implies, a zealous, heartfelt belief in the Christian system; yet with such adjuncts and coexisting persuasions, as to us might seem rather surprising. One or two more of these his Aphorisms, relative to this subject, we shall cite, as likely to be better than any description of ours.

The whole Essay at the end of Volume First, entitled Die Christenheit oder Europa

(Christianity or Europe) is also well worthy of study, in this as in many other points of view.

‘Religion contains infinite sadness. If we are to love God, he must be in distress (hulfsbedurftig, help-needing). In how far is this condition answered in Christianity?–

‘Spinoza is a God-intoxicated man (Gott-trunkener Mensch).–

‘Is the Devil, as the Father of Lies, himself but a necessary illusion?–

‘The Catholic Religion is to a certain extent applied Christianity. Fichte’s Philosophy too is perhaps applied Christianity.–

‘Can Miracles work Conviction? Or is not real Conviction, this highest function of our soul and personality, the only true God-announcing Miracle?

‘The Christian Religion is especially remarkable, moreover, as it so decidedly lays claim to mere good-will in Man, to his essential Temper, and values this independently of all Culture and Manifestation. It stands in opposition to Science and to Art, and properly to Enjoyment.

‘Its origin is with the common people. It inspires the great majority of the limited in this Earth.

‘It is the Light that begins to shine in the Darkness.

‘It is the root of all Democracy, the highest Fact in the Rights of Man (die hochste Thatsache der Popularitat).

‘Its unpoetic exterior, its resemblance to a modern family-picture, seems only to be lent it.

‘Martyrs are spiritual heroes. Christ was the greatest martyr of our species; through him has martyrdom become infinitely significant and holy.–

‘The Bible begins nobly, with Paradise, the symbol of youth; and concludes with the Eternal Kingdom, the Holy City. Its two main divisions, also, are genuine grand-historical divisions (acht gross his torisch). For in every grand-historical compartment (Glied), the grand history must lie, as it were, symbolically re-created (verjungt, made young again). The beginning of the New Testament is the second higher Fall (the Atonement of the Fall), and the commencement of the new Period. The history of every individual man should be a Bible. Christ is a new Adam. A Bible is the highest problem of Authorship.–

‘As yet there is no Religion. You must first make a Seminary (Bildungs-schule) of genuine Religion. Think ye that there is Religion? Religion has to be made and produced (gemacht und hervorgebracht) by the union of a number of persons.’

Hitherto our readers have seen nothing of Novalis in his character of Poet, properly so called; the Pupils at Sais being fully more of a scientific than poetic nature. As hinted above, we do not account his gifts in this latter province as of the first, or even of a high order; unless, indeed, it be true, as he himself maintains, that ‘the distinction of Poet and Philosopher is apparent only, and to the injury of both.’

In his professedly poetical compositions there is an indubitable prolixity, a degree of languor, not weakness but sluggishness; the meaning is too much diluted; and diluted, we might say, not in a rich, lively, varying music, as we find in Tieck, for example; but rather in a low-voiced, not unmelodious monotony, the deep hum of which is broken only at rare intervals, though sometimes by tones of purest and almost spiritual softness.

We here allude chiefly to his unmetrical pieces, his prose fictions: indeed the metrical are few in number; for the most part, on religious subjects; and in spite of a decided truthfulness both in feeling and word, seem to bespeak no great skill or practice in that form of composition. In his prose style he may be accounted happier; he aims in general at simplicity, and a certain familiar expressiveness; here and there, in his more elaborate passages, especially in his Hymns to the Night, he has reminded us of Herder.

These Hymns to the Night, it will be remembered, were written shortly after the death of his mistress: in that period of deep sorrow, or rather of holy deliverance from sorrow. Novalis himself regarded them as his most finished productions. They are of a strange, veiled, almost enigmatical character; nevertheless, more deeply examined, they appear nowise without true poetic worth; there is a vastness, an immensity of idea; a still solemnity reigns in them, a solitude almost as of extinct worlds.

Here and there too some light-beam visits us in the void deep; and we cast a glance, clear and wondrous, into the secrets of that mysterious soul. A full commentary on the Hymns to the Night would be an exposition of Novalis’s whole theological and moral creed: for it lies recorded there, though symbolically, and in lyric, not in didactic language. We have translated the Third, as the shortest and simplest; imitating its light, half-measured style, above all deciphering its vague deep-laid sense, as accurately as we could.

By the word ‘Night,’ it will be seen, Novalis means much more than the common opposite of Day. ‘Light’ seems, in these poems, to shadow forth our terrestrial life; Night the primeval and celestial life:

‘Once when I was shedding bitter tears, when dissolved in pain my Hope had melted away, and I stood solitary by the grave that in its dark narrow space concealed the Form of my life; solitary as no other had been; chased by unutterable anguish; powerless; one thought and that of misery; –here now as I looked round for help; forward could not go, nor backward, but clung to a transient extinguished Life with unutterable longing; –lo, from the azure distance, down from the heights of my old Blessedness, came a chill breath of Dusk, and suddenly the band of Birth, the fetter of Life was snapped asunder.

Vanishes the Glory of Earth, and with it my Lamenting; rushes together the infinite Sadness into a new unfathomable World: thou Night’s-inspiration, Slumber of Heaven, camest over me; the scene rose gently aloft; over the scene hovered my enfranchised new-born spirit; to a cloud of dust that grave changed itself; through the cloud I beheld the transfigured feature of my Beloved.

In her eyes lay Eternity; I clasped her hand, and my tears became a glittering indissoluble chain. Centuries of Ages moved away into the distance, like thunder-clouds. On her neck I wept, for this new life, enrapturing tears. –It was my first, only Dream; and ever since then do I feel this changeless everlasting faith in the Heaven of Night, and its Sun my Beloved.’

To be continued…

Thomas Carlyle: On Novalis 3/5

Excerpt: “Critical and Miscellaneous Essays: Novalis” by Thomas Carlyle, 1829.

How deeply these and the like principles had impressed themselves on Novalis, we see more and more, the farther we study his Writings. Naturally a deep, religious, contemplative spirit; purified also, as we have seen, by harsh Affliction, and familiar in the ‘Sanctuary of Sorrow,’ he comes before us as the most ideal of all Idealists.

For him the material Creation is but an Appearance, a typical shadow in which the Deity manifests himself to man. Not only has the unseen world a reality, but the only reality: the rest being not metaphorically, but literally and in scientific strictness, ‘a show’; in the words of the Poet, ‘Schall und Rauch umnebelnd Himmels Gluth, Sound and Smoke overclouding the Splendour of Heaven.’ The Invisible World is near us: or rather it is here, in us and about us; were the fleshly coil removed from our Soul, the glories of the Unseen were even now around us; as the Ancients fabled of the Spheral Music.

Thus, not in word only, but in truth and sober belief, he feels himself encompassed by the Godhead; feels in every thought, that ‘in Him he lives, moves, and has his being.’

On his Philosophic and Poetic procedure, all this has its natural influence. The aim of Novalis’ whole Philosophy, we might say, is to preach and establish the Majesty of Reason, in that stricter sense; to conquer for it all provinces of human thought, and everywhere reduce its vassal, Understanding, into fealty, the right and only useful relation for it. Mighty tasks in this sort lay before himself; of which, in these Writings of his, we trace only scattered indications. In fact, all that he has left is in the shape of Fragment; detached expositions and combinations, deep, brief glimpses: but such seems to be their general tendency.

One character to be noted in many of these, often too obscure speculations, is his peculiar manner of viewing Nature: his habit, as it were, of considering Nature rather in the concrete, not analytically and as a divisible Aggregate, but as a self-subsistent universally connected Whole. This also is perhaps partly the fruit of his Idealism. ‘He had formed the plan,’ we are informed, ‘of a peculiar Encyclopedical Work, in which experiences and ideas from all the different sciences were mutually to elucidate, confirm and enforce each other.’

In this work he had even made some progress. Many of the ‘Thoughts,’ and short Aphoristic observations, here published, were intended for it; of such, apparently, it was, for the most part, to have consisted.

As a Poet, Novalis is no less Idealistic than as a Philosopher. His poems are breathings of a high devout soul, feeling always that here he has no home, but looking, as in clear vision, to a ‘city that hath foundations.’ He loves external Nature with a singular depth; nay, we might say, he reverences her, and holds unspeakable communings with her: for Nature is no longer dead, hostile Matter, but the veil and mysterious Garment of the Unseen; as it were, the Voice with which the Deity proclaims himself to man.

These two qualities, — his pure religious temper, and heartfelt love of Nature, — bring him into true poetic relation both with the spiritual and the material World, and perhaps constitute his chief worth as a Poet; for which art he seems to have originally a genuine, but no exclusive or even very decided endowment.

His moral persuasions, as evinced in his Writings and Life, derive themselves naturally enough from the same source. It is the morality of a man, to whom the Earth and all its glories are in truth a vapour and a Dream, and the Beauty of Goodness the only real possession. Poetry, Virtue, Religions, which for other men have but, as it were, a traditionary and imagined existence, are for him the everlasting basis of the Universe; and all earthly acquirements, all with which Ambition, Hope, Fear, can tempt us to toil and sin, are in very deed but a picture of the brain, some reflex shadowed on the mirror of the Infinite, but in themselves air and nothingness.

Thus, to live in that Light of Reason, to have, even while here and encircled with this Vision of Existence, our abode in that Eternal City, is the highest and sole duty of man. These things Novalis figures to himself under various images: sometimes he seems to represent the Primeval essence of Being as Love; at other times, he speaks in emblems, of which it would be still more difficult to give a just account; which, therefore, at present, we shall not farther notice.

For now, with these far-off sketches of an exposition, the reader must hold himself ready to look into Novalis, for a little, with his own eyes. Whoever has honestly, and with attentive outlook, accompanied us along these wondrous outskirts of Idealism, may find himself as able to interpret Novalis as the majority of German readers would be; which, we think, is fair measure on our part. We shall not attempt any farther commentary; fearing that it might be too difficult and too unthankful a business. Our first extract is from the Lehrlinge zu Sais (Pupils at Sais), adverted to above.

That ‘Physical Romance,’ which, for the rest, contains no story or indication of a story, but only poetised philosophical speeches, and the strangest shadowy allegorical allusions, and indeed is only carried the length of two Chapters, commences, without note of preparation, in this singular wise:

I. The Pupil. — Men travel in manifold paths: whoso traces and compares these, will find strange Figures come to light; Figures which seem as if they belonged to that great Cipher-writing which one meets with everywhere, on wings of birds, shells of eggs, in clouds, in the snow, in crystals, in forms of rocks, in freezing waters, in the interior and exterior of mountains, of plants, animals, men, in the lights of the sky, in plates of glass and pitch when touched and struck on, in the filings round the magnet, and the singular conjunctures of Chance.

In such Figures one anticipates the key to that wondrous Writing, the grammar of it; but this Anticipation will not fix itself into shape, and appears as if, after all, it would not become such a key for us. An Alcahest seems poured out over the senses of men. Only for a moment will their wishes, their thoughts thicken into form. Thus do their Anticipations arise; but after short whiles, all is again swimming vaguely before them, even as it did.

‘From afar I heard say, that Unintelligibility was but the result of Unintelligence; that this sought what itself had, and so could find nowhere else; also that we did not understand Speech, because Speech did not, would not, understand itself; that the genuine Sanscrit spoke for the sake of speaking, because speaking was its pleasure and its nature.

‘Not long thereafter, said one: No explanation is required for Holy Writing. Whoso speaks truly is full of eternal life, and wonderfully related to genuine mysteries does his Writing appear to us, for it is a Concord from the Symphony of the Universe.

‘Surely this voice meant our Teacher; for it is he that can collect the indications which lie scattered on all sides. A singular light kindles in his looks, when at length the high Rune lies before us, and he watches in our eyes whether the star has yet risen upon us, which is to make the Figure visible and intelligible. Does he see us sad, that the darkness will not withdraw? He consoles us, and promises the faithful assiduous seer better fortune in time. Often has he told us how, when he was a child, the impulse to employ his senses, to busy, to fill them, left him no rest.

He looked at the stars, and imitated their courses and positions in the sand. Into the ocean of air he gazed incessantly; and never wearied contemplating its clearness, its movements, its clouds, its lights. He gathered stones, flowers, insects, of all sorts, and spread them out in manifold wise, in rows before him. To men and animals he paid heed; on the shore of the sea he sat, collected mussels. Over his own heart and his own thoughts he watched attentively. He knew not whither his longing was carrying him.

As he grew up, he wandered far and wide; viewed other lands, other seas, new atmospheres, new rocks, unknown plants, animals, men; descended into caverns, saw how in courses and varying strata the edifice of the Earth was completed, and fashioned clay into strange figures of rocks. By and by, he came to find everywhere objects already known, but wonderfully mingled, united; and thus often extraordinary things came to shape in him. He soon became aware of combinations in all, of conjunctures, concurrences. Erelong, he no more saw anything alone. — In great variegated images, the perceptions of his senses crowded round him; he heard, saw, touched and thought at once.

He rejoiced to bring strangers together. Now the stars were men, now men were stars, the stones animals, the clouds plants; he sported with powers and appearances; he knew where and how this and that was to be found, to be brought into action; and so himself struck over the strings, for tones and touches of his own.

‘What has passed with him since then he does not disclose to us. He tells us that we ourselves, led on by him and our own desire, will discover what has passed with him. Many of us have withdrawn from him. They returned to their parents, and learned trades. Some have been sent out by him, we know not whither; he selected them. Of these, some have been but a short time there, others longer. One was still a child; scarcely was he come, when our Teacher was for passing him any more instruction.

This child had large dark eyes with azure ground, his skin shone like lilies, and his locks like light little clouds when it is growing evening. His voice pierced through all our hearts; willingly would we have given him our flowers, stones, pens, all we had. He smiled with an infinite earnestness; and we had a strange delight beside him. One day he will come again, said our Teacher, and then our lessons end. –Along with him he sent one, for whom we had often been sorry. Always sad he looked; he had been long years here; nothing would succeed with him; when we sought crystals or flowers, he seldom found. He saw dimly at a distance; to lay down variegated rows skilfully he had no power. He was so apt to break everything. Yet none had such eagerness, such pleasure in hearing and listening.

At last, –it was before that Child came into our circle, –he all at once grew cheerful and expert. One day he had gone out sad; he did not return, and the night came on. We were very anxious for him; suddenly, as the morning dawned, we heard his voice in a neighbouring grove. He was singing a high, joyful song; we were all surprised; the Teacher looked to the East, such a look as I shall never see in him again. The singer soon came forth to us, and brought, with unspeakable blessedness on his face, a simple-looking little stone, of singular shape.

The Teacher took it in his hand, and kissed him long; then looked at us with wet eyes, and laid this little stone on an empty space, which lay in the midst of other stones, just where, like radii, many rows of them met together.

‘I shall in no time forget that moment. We felt as if we had had in our souls a clear passing glimpse into this wondrous World.’

In these strange Oriental delineations the judicious reader will suspect that more may be meant than meets the ear. But who this teacher at Sais is, whether the personified Intellect of Mankind; and who this bright-faced golden-locked Child (Reason, Religious Faith?), that was ‘to come again,’ to conclude these lessons; and that awkward unwearied Man (Understanding?), that ‘was so apt to break everything,’ we have no data for determining, and would not undertake to conjecture with any certainty. We subjoin a passage from the second chapter, or section, entitled ‘Nature,’ which, if possible, is of a still more surprising character than the first.

After speaking at some length on the primeval views Man seems to have formed with regard to the external Universe, or ‘the manifold Objects of his Senses’; and how in those times his mind had a peculiar unity, and only by Practice divided itself into separate faculties, as by Practice it may yet farther do, ‘our Pupil’ proceeds to describe the conditions requisite in an inquirer into Nature, observing, in conclusion, with regard to this,–

‘No one, of a surety, wanders farther from the mark than he who fancies to himself that he already understands this marvellous Kingdom, and can, in few words, fathom its constitution, and everywhere find the right path. To no one, who has broken off, and made himself an Island, will insight rise of itself, nor even without toilsome effort. Only to children, or childlike men, who know not what they do, can this happen. Long, unwearied intercourse, free and wise Contemplation, attention to faint tokens and indications; an inward poet-life, practised senses, a simple and devout spirit: these are the essential requisites of a true Friend of Nature; without these no one can attain his wish.

Not wise does it seem to attempt comprehending and understanding a Human World without full perfected Humanity. No talent must sleep; and if all are not alike active, all must be alert, and not oppressed and enervated. As we see a future Painter in the boy who fills every wall with sketches and variedly adds colour to figure; so we see a future Philosopher in him who restlessly traces and questions all natural things, pays heed to all, brings together whatever is remarkable, and rejoices when he has become master and possessor of a new phenomenon, of a new power and piece of knowledge.

‘Now to Some it appears not at all worth while to follow out the endless divisions of Nature; and moreover a dangerous undertaking, without fruit and issue. As we can never reach, say they, the absolutely smallest grain of material bodies, never find their simplest compartments, since all magnitude loses itself, forwards and backwards, in infinitude; so likewise is it with the species of bodies and powers; here too one comes on new species, new combinations, new appearances, even to infinitude.

These seem only to stop, continue they, when our diligence tires; and so it is spending precious time with idle contemplations and tedious enumerations; and this becomes at last a true delirium, a real vertigo over the horrid Deep. For Nature too remains, so far as we have yet come, ever a frightful Machine of Death: everywhere monstrous revolution, inexplicable vortices of movement; a kingdom of Devouring, of the maddest tyranny; a baleful Immense: the few light-points disclose but a so much the more appalling Night, and terrors of all sorts must palsy every observer.