Category Archives: de Staël

Madame de Staël: Goethe’s Egmont 1/2

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. III, 146-153.

If my Life was a mirror in which thou

Did love to contemplate thyself,

So be also my death.

Men are not together only

When in each other’s presence;

The distant, the departed,

Also live for us.

I shall live for thee,

And for myself,

I have lived long enough.

“The Count of Egmont” appears to me the finest of Goethe’s tragedies; he wrote it, I believe, at the same time, when he composed Werther; the same warmth of soul is alike in both. The play begins at the moment when Philip II, weary of the mild government of Margaret of Parma, in the Low Countries, sends the Duke of Alva to supply her place.

William of Orange

The king is troubled by the popularity which the Prince of Orange and the Count of Egmont have acquired; he suspects them of secretly favouring the partizans of the reformation. Every thing is brought together that can furnish the most attractive idea of the Count of Egmont; he is seen adored by the soldiers at the head of whom he has borne away so many victories.

The Spanish princess trusts his fidelity, even though she knows how much he censures the severity that has been employed against the Protestants. The citizens of Brussels look on him as the defender of their liberties before the throne; and to complete the picture, the Prince of Orange, whose profound policy and silent wisdom are so well known in history sets off still more the generous imprudence of Egmont, in vainly entreating him to depart with himself before the arrival of the Duke of Alva. The Prince of Orange is a wise and noble character; an heroic but inconsiderate self-devotion can alone resist his counsels.

The Count of Egmont resolves not to abandon the inhabitants of Brussels; he trusts himself to his fate, because his victories have taught him to reckon upon the favours of fortune, and he always preserves in public business the same qualities that have thrown so much brilliancy over his military character.

Egmont, on the contrary,

Advances with a bold step,

As if the world were all his own.

These noble and dangerous qualities interest us in his destiny; we feel on his account fears which his intrepid soul never allowed him to experience for himself; the general effect of his character is displayed with great art in the impression which it is made to produce on all the different persons by whom he is surrounded. It is easy to trace a lively portrait of the hero of a piece; it requires more talent to make him known by the admiration that he inspires in his soldiers, the people, the great nobility, in all that bear any relation to him.

The Count of Egmont is in love with a young girl, Clara, born in the class of citizens at Brussels; he goes to visit her in her obscure retreat. This love has a larger place in the heart of the young girl than in his own; the imagination of Clara is entirely subdued by the lustre of the Count of Egmont, by the dazzling impression of his heroic valour and brilliant reputation.

There are goodness and gentleness in the love of Egmont; in the society of this young person he find repose from trouble and solicitude. “They speak to you,” he said, “of this Egmont, silent, severe, authoritative; who is made to struggle with events and with mankind; but he who is simple, loving, confiding, happy, that Egmont, Clara, is thine.”

The love of Egmont for Clara would not be sufficient for the interest of the piece; but when misfortunate is joined to it, this sentiment which before appeared only in the distance, acquires an admirable strength.

Duke of Alva

The arrival of the Spaniards with the Duke of Alva at their head being made known, the terror spread by that gloomy nation amongst the joyous people of Brussels is described in a superior manner. At the approach of a violent storm, men retire to their houses, animals tremble, birds take a low flight, and seem to seek an asylum in the earth — all nature seems to prepare itself to meet the scourge which threatens it — thus terror possessed the minds of the unfortunate inhabitants of Flanders. The Duke of Alva is not willing to have the Count of Egmont arrested in the streets of Brussels, he fears an insurrection of the people, and wishes if possible to draw his victim to his own palace, which commands the city, and adjoins the citadel.

The matter turns upon a single point:

He would have me live as I cannot.

He employs his own son, young Ferdinand, to prevail on the man he wishes to ruin, to enter his abode. Ferdinand is an enthusiastic admirer of the hero of Flanders, he has no suspicion of the horrid designs of his father, and displays a warmth and ardour of character which persuades the Count of Egmont that the father of such a son cannot be his enemy. Egmont consents to accompany him to the Duke of Alva. That perfidious and faithful representative of Phillip II expects him with an impatience which makes one shudder. He places himself at the window, and perceives him at a distance, mounted on a superb horse, which he had taken in one of his victorious battles.

The Duke of Alva feels a cruel and increasing joy at every step which Egmont makes towards his palace. When the horse stops, he is agitated; his guilty heart pants to effect his criminal purpose, and when Egmont enters the court he cries: “One foot is in the tomb, another step! the grated entrance closes on him, and now! he is mine!”

The Count of Egmont having entered, the Duke discourses with him for some time on the government of the Low Countries, and on the necessity of employing rigour to restrain the progress of the new opinions. He has no longer any interest in deceiving Egmont, and yet he feels a pleasure in the success of his craftiness, and wishes still to enjoy it a few moments. At length, he rouses the generous soul of Egmont and irritates him by disputation in order to draw from him some violent expressions.

He affects to be provoked by them, and performs, as by a sudden impulse, what he had calculated on and determined to do long before. Why so many precautions with a man who is already in his power, and whom he has determined to deprive, in a few hours, of existence? It is because the political assassin always retains a confused desire to justify himself, even in the eye of his victim. He wishes to say something in his excuse even when all he can allege persuades neither himself nor any other person.

Perhaps no man is capable of entering on a criminal act without some subterfuge, and therefore the true morality of dramatic works consists not in poetical justice which the author dispenses as he thinks fit, and of which history so often shews us the fallacy, but in the art of painting vice and virtue in such colours as to inspire us with hatred to the one and love to the other.

The report of the Count of Egmont’s arrest was scarcely spread through Brussels before it is known that he must perish. No one expects that justice will be heard. His terrified adherents ventured not a word in his defense, and suspicion soon separates those whom the same interest had united. An apparent submission arises from the terror which every individual feels and inspires in his turn, and the panic which pervades them all, that popular cowardice which so quickly succeeds a state of unusual exaltation, is in this part of the work most admirably described.

Clara alone, that timid girl who scarcely ever ventured to leave her own abode, appears in the public square at Brussels, reassembles by her cries the citizens who had dispersed, recalls to their recollection the enthusiasm which the name of Egmont had inspired, the oath they had taken to die for him. All who heard her shudder! “Young woman,” says a citizen of Brussels; “speak not of Egmont, his name is fatal to us.”

“What! Shall I not pronounce his name?” cried Clara. “Have you not all invoked it a thousand times? Is it not written on every thing around us? Have I not seen its brilliant character traced even by the stars of Heaven? Shall I not then name it? Worthy people! What are you about? Is your mind perplexed, your reason lost? Look not upon me with that unquiet and apprehensive air. Cast not down your eyes in terror.

What I demand is also what you yourselves desire. Is not my voice the voice of your own heart? Ask of each other, which of you will not this very night prostrate himself before God to beg the life of Egmont? Which of you in his own house will not repeat, ‘The liberty of Egmont, or death?'”

To be continued …

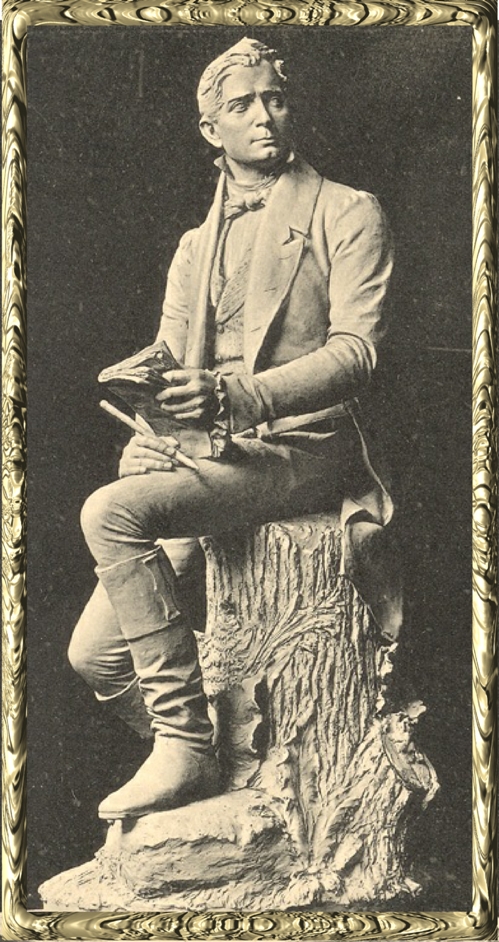

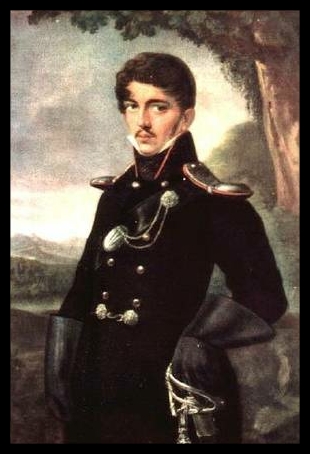

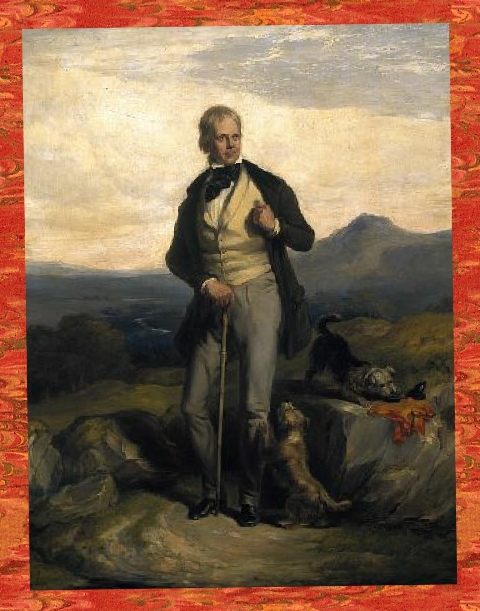

Lamoral, Count of Egmont, Prince of Gavre

1522-1568

From an 1888 Engraving

Madame de Staël: Goethe’s Egmont 2/2

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. III, 153-162.

Child! Child! Forbear!

As if goaded by invisible spirits,

The sun steeds of time bear onward

The light car of our destiny

And nothing remains for us

But, with calm self-possession,

Firmly, to grasp the reins, and

Now right, now left,

To steer the wheels here from the precipice

And there from the rock.

Whether he is hasting, who knows?

Does anyone consider whence he came?

A citizen of Brussels: “God forbid that we should listen to you any longer! Some misfortune would be the consequence of it.”

Clara: “Stay, stay! Do not leave me because I speak of him whom with so much ardour you press’d forward to meet when public report announced his arrival; when each of you exclaimed, Egmont comes! He comes! Then, the inhabitants of the streets through which he was to pass, esteemed themselves happy; as soon as the footstep of his horse was heard, each abandoned his labour to run out to meet him, and the beam which shot from his eye, coloured your dejected countenances with hope and joy.

Some among you carried their children to the threshold of the door, and raising them in their arms, cried out, ‘Behold, this is the great Egmont, it is! He, who will procure for you times far happier than those which your poor fathers have endured.’ Your children will demand of you, what is become of the times which you then promised them? What! We lose our moments in vain words! You are inactive, you betray him!”

Brackenbourg, the friend of Caral, conjures her to go home. “What will your mother say?” cries he.

Clara: “Thinkest thou that I am a child, or bereft of my senses? No, they must listen to me: Hear me, fellow citizens! I see that you are perplexed, and that you can scarcely recollect yourselves amidst the dangers which threaten you. Suffer me to draw your attention to the past – alas! even to the past of yesterday. Think on the future; can you live? Will they suffer you to live, if he perishes? With him the last breath of your liberty will be extinguished. Was he not everything to you? For whom, then did he expose himself to dangers without number? His wounds — he received them for you; that great soul, wholly devoted to your service, now wastes its energies in a dungeon.

Murder spreads its snares around him; he thinks of you, perhaps he still hopes in you. For the first time he stands in need of your assistance. He, who to this very day, has been employed only in heaping on you his services and his benefactions.”

A Citizen of Brussels (to Brackenbourg): “Send her away, she afflicts us.”

Clara: “How, then! I have no strength, no arms skillful in battle as yours are; but I have what you want, courage and contempt of danger! Why cannot I infuse my soul into yours? I will go forth in the midst of you: A defenseless standard has often rallied a noble army. My spirit shall be like a flame preceding your steps; enthusiasm and love shall at length re-unite this dispersed and wavering people.”

Brackenbourg informs Clara that they perceive not far from them some Spanish soldiers who may possibly listen to them. “My friend,” said he, “consider in what place we are.”

Clara: “In what place! Under that heaven whose magnificent vault seems to bow with complacency on the head of Egmont when he appeared. Conduct me to his prison, you know the road to the old castle. Guide my steps, I will follow you.”

Brackenbourg draws Clara to her own habitation, and goes out again to enquire the fate of the Count of Egmont. He returns, and Clara, whose last resolution is already taken, insists on his relating to her all that he has heard.

“Is he condemned?” (she exclaims.)

Brackenbourg: “He is, I cannot doubt of it.”

Clara: “Does he still live?”

Brackenbourg: “Yes.”

Clara: “And how can you assure me of it? Tyranny destroys the generous man during the darkness of the night, and hides his blood from every eye — the people, oppressed and overwhelmed, sleep and dream that they will rescue him, and during that time his indignant spirit has already quitted this world. He is no more! Do not deceive me, he is no more!”

Brackenbourg: “No, I repeat it, alas! He still lives, because the Spaniards destined for the people they mean to oppress, a terrifying spectacle; a sight which must break every heart in which the spirit of liberty still resides.”

Clara: “You may speak out: I also will tranquilly listen to the sentence of my death. I already approach the region of the blessed. Already consolation reaches me from that abode of peace. Speak.”

Brackenbourg: “The reports which circulate, and the doubled guard, made me suspect that something formidable was prepared this night on the public square. By various windings I got to a house, whose windows front that way; the wind agitated the flambeaux, which was borne in the hands of a numerous circle of Spanish soldiers; and as I endeavored to look through that uncertain light, I shuddered on perceiving a high scaffold; several people were occupied in covering the floor with black cloth, and the steps of the staircase were already invested with that funereal garb.

One might have supposed they were celebrating the consecration of some horrible sacrifice. A white crucifix, which during the night shone like silver, was placed on one side of the scaffold. The terrible certainty was there, before my eyes; but the flambeaux by degrees were extinguished, every object soon disappeared, and the criminal work of darkness retired again into the bosom of night.”

The son of the Duke of Alva discovers that he has been made the instrument of Egmont’s destruction, and he determines, at all hazards, to save him; Egmont demands of him only one service, which is to protect Clara when he shall be no more. But we learn that, resolved not to survive the man she loves, she has destroyed herself. Egmont is executed; and the bitter resentment which Ferdinand feels against his father is the punishment of the Duke of Alva, who, it is said, never loved anything on earth except his son.

It seems to me that with a few variations, it would be possible to adapt this play to the French model. I have passed over in silence some scenes which could not be introduced on our theatre. In the first place, that with which the tragedy begins: some of Egmont’s soldiers, and some citizens of Brussels, are conversing together on the subject of his exploits. In a dialogue, very lively and natural, they relate the principal actions of his life, and in their language and narratives, shew the high confidence with which he had inspired them.

‘Tis thus that Shakespeare prepares the entrance of Julius Caesar; and the Camp of Wallenstein is compared with the same intention. But in France, we should not endure a mixture of the language of the people with that of tragic dignity; and this frequently gives monotony to our second-rate tragedies. Pompous expressions, and heroic situations, are necessarily few in number. And besides, tender emotions rarely penetrate to the bottom of the soul when the imagination is not previously captivated by those simple but true details which give life to the smallest circumstances.

The family to which Clara belongs is represented as completely that of a citizen; her mother is extremely vulgar. He who is to marry her, is indeed passionately attached to her, but one does not like to consider Egmont as the rival of such an inferior man; it is true that everything which surrounds Clara serves to set off the purity of her soul, but nevertheless in France we should not allow in the dramatic of first principles in that of painting, the shade which renders the light more striking.

As we see both of these at once in a picture, we receive, at the same time, the effect of both. It is not the same in a theatrical performance where the action follows in succession; the scene which hurts our feelings is not tolerated in consideration of the advantageous light it is to throw on the following scene; and we expect that the contrast shall consist in beauties, different indeed, but which shall nevertheless be beauties.

The conclusion of Goethe’s tragedy does not harmonize with the former part; the Count of Egmont falls asleep a few minutes before he ascends the scaffold. Clara, who is dead, appears to be him during his sleep, surrounded by celestial brilliance, and informs him that the cause of liberty, which he had served so well, will one day triumph. This wonderful denouement cannot accord with an historical performance.

The Germans are, in general, embarrassed about the conclusion of their pieces; and the Chinese proverb is particularly applicable to them, which says, “When we have ten steps to take, the ninth brings us half way.” The talent necessary to finish a composition of any kind demands a sort of cleverness, and of calculation, which agrees but badly with the vague and indefinite imagination displayed by the Germans in all their works.

Besides, it requires art, and a great deal of art, to find a proper denouement, for there are seldom any in real life: Facts are linked one to the other, and their consequences are lost in the lapse of time. The knowledge of the theatre alone teaches us to circumscribe the principal event, and make all the accessory ones concur to the same purpose. But to combine effects seems to the Germans almost like hypocrisy, and the spirit of calculation appears to them irreconcilable with inspiration.

Of all the writers, however, Goethe is certainly best able to unite the frailties of genius with its bolder flights; but he does not vouchsafe to give himself the trouble of arranging dramatic situations so as to render them properly theatrical. If they are fine in themselves, he cares for nothing else.

His German audience at Weimar ask no better than to wait the development of his plans, and to guess at his intention — as patient, as intelligent, as the ancient Greek chorus, they do not expect merely to be amused as sovereigns commonly do, whether they are people or kings, they contribute to their own pleasure, by analyzing and explaining what did not at first strike them — such a public is truly like an artist in its judgments.

I stand high, but I can and must rise yet higher.

Courage, strength and hope possess my soul.

Not yet, have I attained the height of my ambition;

That once achieved, I will stand firmly and without fear.

Should I fall, should a thunderclap, a storm blast,

Ay, a false step of my own,

Precipitate me into the abyss,

So be it.

I shall lie there with thousands of others.

I have never distained, even for a trifling stake,

To throw the bloody die with my gallant comrades,

And shall I hesitate now,

When all that is most precious in life

Is set upon the cast?

Egmont and Hoorn

.

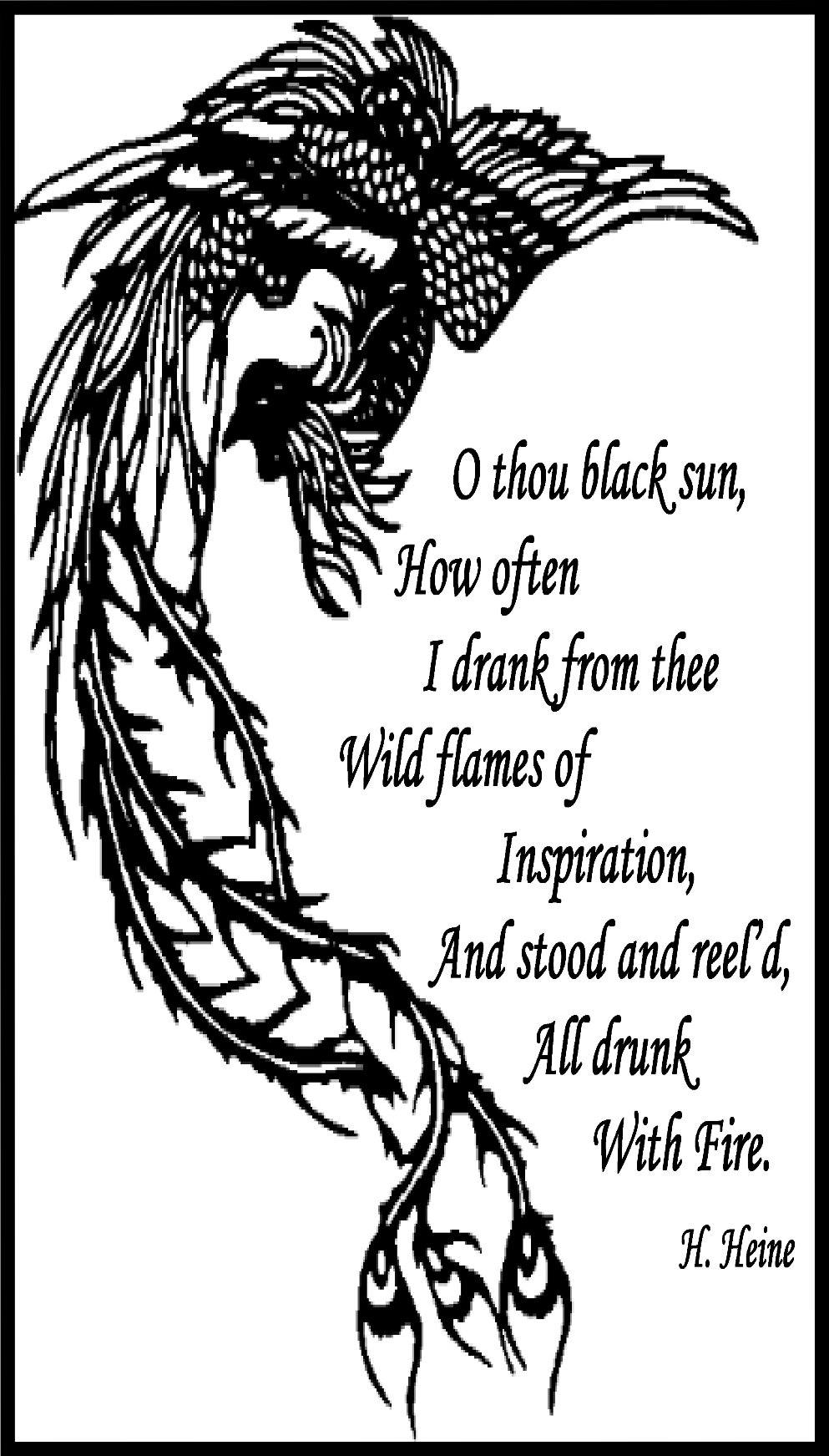

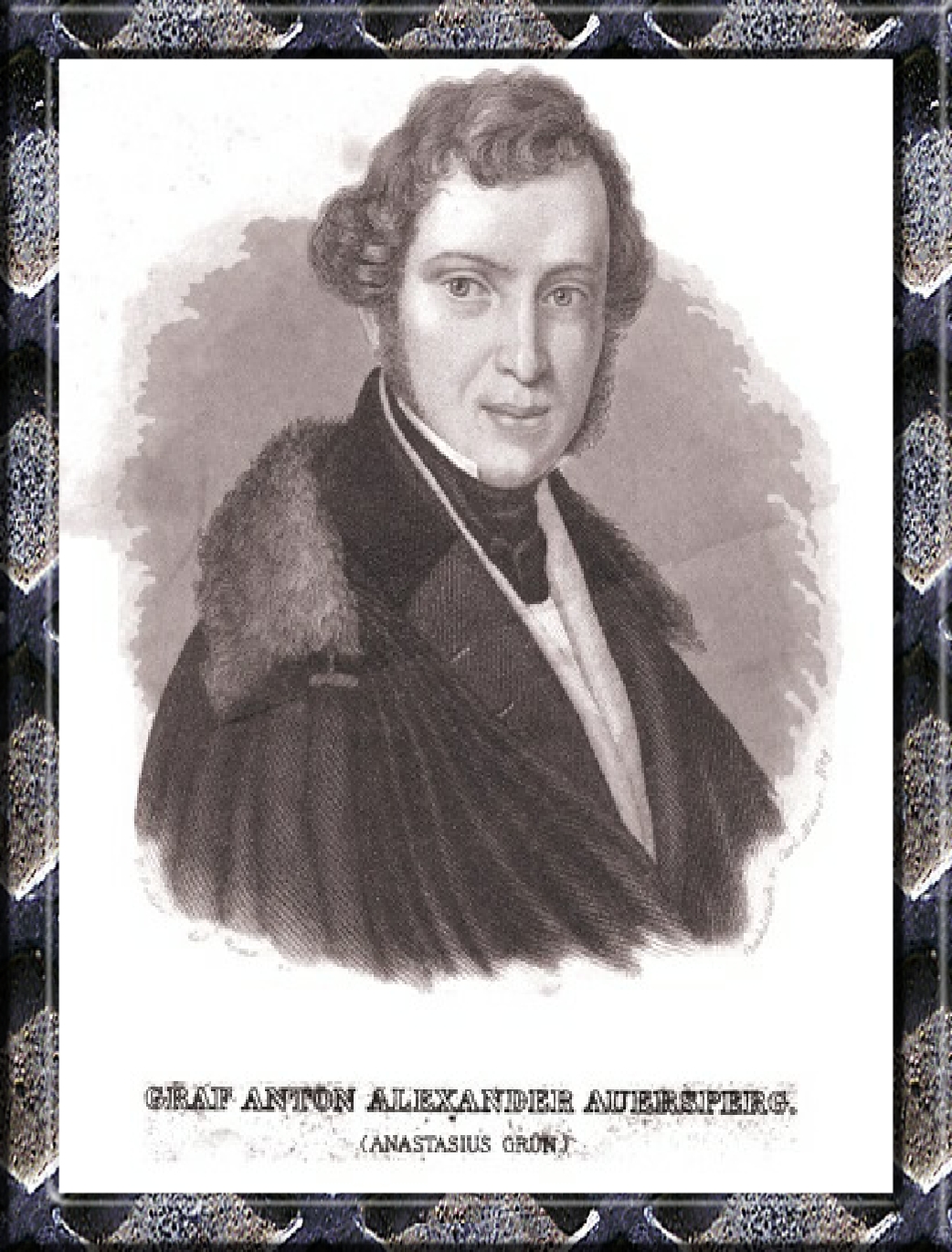

Madame de Staél: “Of German Poetry: Gottfried August Bürger and The Wild Huntsman” (2 of 2)

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. I. Illustrationen zu Bürgers Werk.

Burger has written another story, less celebrated, but also extremely original, entitled “The Wild Huntsman.” Followed by his servants and a large pack of hounds, he sets out for the chase on a Sunday, just as the village bell announces divine service.

A knight in white armour presents himself, and conjures him not to profane the Lord’s day. Another knight, arrayed in black armour, makes him ashamed of subjecting himself to prejudices which are suitable only to old men and children.

The huntsman yields to these evil suggestions. He sets off and reaches the field of a poor widow. She throws herself at his feet, imploring him not to destroy her harvest by trampling down her corn with his attendants.

The knight in white armour entreats the huntsman to listen to the voice of pity. The black knight laughs at a sentiment so puerile; the huntsman mistakes ferocity for energy, and his horses trample on the hope of the poor and the orphan.

At length the stag, pursued, seeks refuge in the hut of an old hermit. The huntsman wishes to set it on fire in order to drive out his prey. The hermit embraces his knees, and endeavors to soften the ferocious being who thus threatens his humble abode. For the last time, the good genius, under the form of the white knight, again speaks to him. The evil genius, under that of the black knight, triumphs. The huntsman kills the hermit, and is at once changed into a phantom, pursued by his own dogs, who seek to devour him.

This story is derived from a popular superstition. It is said, that at midnight in certain seasons of the year, a huntsman is seen in the clouds, just over the forest where this event is supposed to have passed, and that he is pursued by a furious pack of hounds till day-break.

What is truly fine in this poem of Bürger’s is his description of the ardent will of the huntsman: It is at first innocent, as are all the faculties of the soul; but it becomes more and more depraved, as often as he resists the voice of conscience and yields to his passions. His headstrong purpose was at first only the intoxication of power. It soon becomes that of guilt, and the earth can no longer sustain him. The good and evil inclinations of men are well characterized by the white and black knights; the words, always the same, which are pronounced by the white knight to stop the career of the huntsman, are also very ingeniously combined.

The ancients, and the poets of the middle ages, were well acquainted with the kind of terror caused in certain circumstances by the repetition of the same words; it seems to awaken the sentiment of inflexible necessity. Apparitions, oracles, all supernatural powers, must be monotonous: what is immutable is uniform; and in certain fictions it is a great art to imitate by words that solemn fixedness which imagination assigns to the empire of darkness and of death.

We also remark in Bürger a certain familiarity of expression, which does not lessen the dignity of the poetry, but, on the contrary, singularly increases its effect. When we succeed in exciting both terror and admiration without weakening either, each of those sentiments is necessarily strengthened by the union: it is mixing, in the art of painting, what we see continually with that which we never see; and from what we know, we are led to believe that which astonishes us.

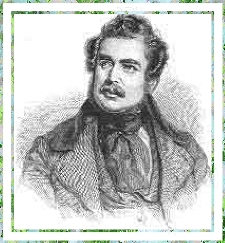

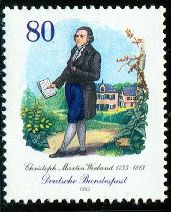

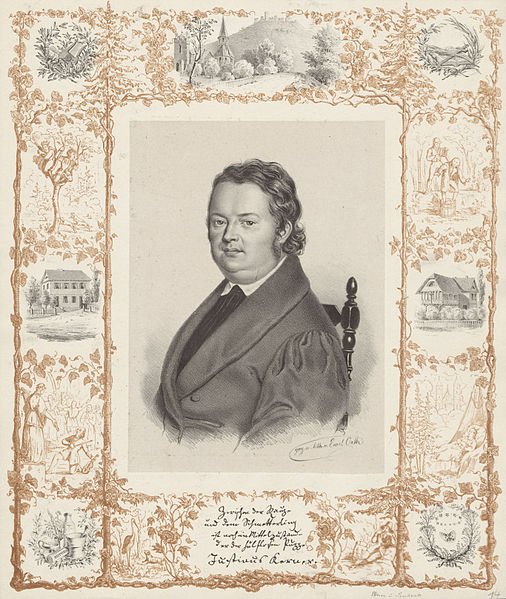

Gottfried August Bürger 1747-1794

Madame de Staél: “Of German Poetry: Gottfried August Bürger and Leonora” (1 of 2)

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. I. Illustrationen zu Bürgers Werk..

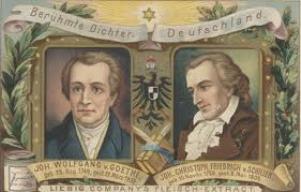

.The detached pieces of poetry among the Germans are, it appears to me, still more remarkable than their poems, and it is particularly that writing on which the stamp of originality is impressed. It is also true that the authors who have written most in this manner, Goethe, Schiller, Bürger, etc, are of the modern school, which alone bears a truly national character. Goethe has most imagination, and Schiller most sensibility; but Gottfried August Bürger is more generally admired than either…

We have not yet spoken of an inexhaustible source of poetical effect in Germany, which is terror: stories of apparitions and sorcerers are equally well received by the populace and by men of more enlightened minds. It is a relick of the northern mythology; a disposition naturally inspired by the long nights of a northern climate; and besides, though Christianity opposes all groundless fears, yet popular superstitions have always some sort of analogy to the prevailing religion. Almost every true opinion has its attendant error, which like a shadow places itself at the side of the reality: it is a luxuriance or excess of belief, which is commonly attached both to religion and to history, and I know not why we should disdain to avail ourselves of it.

Shakespeare has produced wonderful effects from the introduction of spectres and magic; and poetry cannot be popular when it despises that which exercises a spontaneous empire over the imagination. Genius and taste may preside over the arrangement of these tales, and in proportion to the commonness of the subject, the more skill is required in the manner of treating it; perhaps it is in this union alone that the great force of a poem consists. It is probable that the great events recorded in the Iliad and Odyssey were sung by nurses, before Homer rendered them the chef-d’oeuvre of the poetical art.

Of all German writers, Bürger has made the best use of this vein of superstition which carries us so far into the recesses of the heart. His tales are therefore well known throughout Germany. “Leonora,” which is most generally admired, is not yet translated into French, or at least, it would be very difficult to relate it circumstantially either in our prose or verse.

A young girl is alarmed at not hearing from her lover who is gone to the army. Peace is made, and the soldiers return to their habitations. Mothers again meet their sons, sisters their brothers, and husbands their wives. The warlike trumpet accompanies the songs of peace, and joy reigns in every heart.

Leonora in vain surveys the ranks of the soldiers, she sees not her lover, and no one can tell her what is become of him.

She is in despair: her mother attempts to calm her; but the youthful heart of Leonora revolves against the stroke of affliction, and in its frenzy she accuses Providence.

From the moment in which the blasphemy is uttered, we are sensible that the story is to have something fatal in it, and this idea keeps the mind in constant agitation.

At midnight, a knight stops at the door of Leonora’s house. She hears the neighing of the horse and the clinking of the spurs. The knight knocks, she goes down and beholds her lover.

He tells her to follow him instantly, having not a moment to lose, he says, before he returns to the army. She presses forward; he places her behind him on his horse, and sets off with the quickness of lightning.

During the night he gallops through barren and desert countries: his youthful companion is filled with terror, and continually asks him why he goes so fast. The knight still presses on his horse by his hoarse and hollow cries, and in a low voice says, “The dead go quick the dead go quick.”

Leonora answers, “Ah! Leave the dead in peace!” But whenever she addresses to him any anxious question, he repeats the same appalling words.

In approaching the church, where he says he is carrying her to complete their union, the frosts of winter seem to change nature herself into a frightful omen: priests carry a coffin in great pomp, and their black robes train slowly on the snow, the winding sheet of the earth.

Leonora’s terror increases, and her lover cheers her with a mixture of irony and carelessness which makes one shudder. All that he says is pronounced with a monotonous precipitation, as if already, in his language, the accents of life were no longer heard.

He promises to bring her to that narrow and silent abode where their union was to be accomplished. We see at a distance the church-yard by the side of the church.

The knight knocks, and the door opens. He pushes forward with his horse, making him pass between the tombstones. He then by degrees loses the appearance of a living being, is changed into a skeleton, and the earth opens to swallow up both him and his mistress.

I certainly do not flatter myself that I have been able in this abridged recital to give a just idea of the astonishing merit of this tale. All the imagery, all the sounds connected with the situation of the soul, are wonderfully expressed by the poetry: the syllables, the rhymes, all the art of language is employed to excite terror. The rapidity of the horse’s pace seems more solemn and more appalling than even the slowness of a funeral procession. The energy with which the knight quickens his course, that petulance of death, causes an inexpressible emotion; and we feel ourselves carried off by the phantom, as well as the poor girl whom he drags with him into the abyss.

There are four English translations of this tale of Leonora [as of 1810], but the best beyond comparison is that of William Spencer, who of all English poets is best acquainted with the true spirit of foreign languages. The analogy between the English and the German allows a complete transfusion of the originality of style and versification of Bürger; and we not only find in the translation the same ideas as in the original, but also the same sensations; and nothing is more necessary than this to convey the true knowledge of a literary production. It would be difficult to obtain the same result in French, where nothing strange or odd seems natural.

.

Coming soon, Part Two: Madame de Staël : “Of German Poetry: Gottfried August Bürger and The Wild Huntsman”

Madame de Staël: Goethe’s Faust 4

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. II, 192-226. Illustrations by Eugene Delacroix.

“For with fair talents Nature has endow’d me;

Although, alas, she has accompanied

Her lofty gifts with many weaknesses,

With a foreboding spirit, boundless pride,

And sensibility too exquisite.

It cannot be otherwise, since Fate,

In her caprice, has fashioned such a man;

We must consent to take him as he is.”

Faustus learns that Margaret has murdered the child, to which she had given birth, hoping thus to avoid shame. Her crime has been discovered; she has been thrown into prison, and is doomed to perish the next morning on the scaffold. Faustus curses Mephistopheles in the bitterness of rage; Mephistopheles reproaches Faustus in cold blood, and proves to him that it is himself who has desired evil, and that he has assisted him only because called upon by himself to do so. Sentence of death is pronounced against Faustus for having slain Margaret’s brother.

He nevertheless enters the city in secret, obtained from Mephistopheles the means of delivering Margaret, and penetrates at night into her dungeon, of which he has stolen the keys.

He hears from afar off the imperfect notes of a song which sufficiently proves the derangement of her mind; the words of this song are very coarse, and Margaret was naturally pure and delicate. Mad women are generally painted at if madness accommodated itself to the rules of propriety, and only gave the right of breaking off sentences abruptly, and interrupting at convenient times the chain of ideas; but it is not so: real disorder of the mind almost always displays itself in shapes foreign even to the cause of the disorder, and the gaiety of its unhappy victims is more harrowing to the soul than even their misery.

Faustus enters the prison: Margaret believes that they are come to lead her to death. Margaret, rising from her bed of straw, exclaims: “They come! They come! Oh! how bitter is death!”

Faustus, in a low voice: “Softly, softly, I come to deliver thee.” (He draws near her, to break her fetters.)

Margaret: “If thou art human, my despair will touch thee.”

Faustus: “Softer, softer! Thou wilt awake the guard by thy cries.”

Margaret, throwing herself on her knees: “Who hath given thee, barbarian, this power over me? It is only midnight: why does thou come to look for me so soon? Have pity on my tears, let me live a little longer. Tomorrow morning, is it not time enough?” She rises again. “I am so young — so young! and must I then die already? I was once handsome too: That was my ruin. Then my friend was near to me; but now he is a great way off. The flowers of my garland are scattered. Do not grasp my hand with such violence! be tender with me! let me not weep in vain! never, to this day, have I seen thee before.”

Faustus: “How can I support her agony?”

Margaret: “I am altogether in thy power. Only let me suckle my child: I have pressed it slowly to my heart all night long. They have taken it from me to distress me. Don’t they say that I killed it? Never shall I be again what I once was. Did they not sing songs against me, those wicked people? What would they say then?”

Faustus, casting himself to her feet: “Thy lover is at thy feet. He comes to throw open the gates of this horrible prison.”

Margaret: “Yes, let us fall on our knees; let us call the saints to our assistance. The cries of hell are heard, and the evil genii wait for us on the threshold of my dungeon.”

Faustus: “Margaret! Margaret!”

Margaret. listening eagerly: “It was the voice of my love.” She springs toward Faustus, and her irons fall off. “Where is he? I heard him call me. I am free. Nobody can keep me any longer in prison. I will support myself on his arm, I will rest on his bosom. He calls me Margaret; he is there, before the door. Amidst the howling of pitiless death I hear the soft and touching harmony of his voice.”

Faustus: “Yes, Margaret, it is I.”

Margaret: “It is thou; repeat that once again.” (She presses him to her bosom.) “Tis he! Tis he! What is become of the anguish of my chains and of the scaffold? It is thou! I am saved! I see before me the road in which I first beheld thee, the smiling garden where Martha and I used to wait for you.”

Faustus: “Come, come.”

Margaret: “It is so sweet to me to stay with thee! Ah! do not leave me!”

Faustus: “Haste! we may pay dearly for the least delay.”

Margaret: “What! thou answerest not to my embraces? My love, it is so short a time since we parted? Hast thou already forgotten to press me to thy heart? There was a time when thy words and looks called down all Heaven upon me! Embrace me! for mercy’s sake, embrace me! Thy heart then is cold and dumb. What is become of thy love? Who has robbed me of it?”

Faustus: “Come, follow me, my dearest love: take courage. I love thee with rapture, but follow me, it is my only prayer.”

Margaret: “But art thou indeed Faustus? Art thou thyself?”

Faustus: “Yes, certainly. Yes, come along!”

Margaret: “Thou deliverest me from my chains, thou takest me again to thine arms. How is it that thou art not afraid of Margaret? Does thou know well, my love; dost thou well know whom thou deliverest?”

Faustus: “Come, come! The night already begins to fade away!”

Margaret: “My mother! It was I who killed her. My child! It was I who drowned it. Was it not thine as well as mine? Is it true then that I behold thee, Faustus? Is it not a dream? Give me thy hand, thy beloved hand! Oh Heaven! it is moist. Wipe it. I think there is blood upon it. Hide thy sword from me! Where is my brother? I beseech you, hide it from me!”

Faustus: “Oh! bury the irreparable past in oblivion! you make me die.”

Margaret: “No, thou must remain behind. I will describe to thee what manner of tombs thou must prepare tomorrow. The best place must be given to my mother; my brother must be laid next to her. As for me, you must place me farther off; yet not too far neither; and my child, right upon my bosom. But nobody must lie by my side. I could have wished that thou mightest be near me; but that was a sweet and pure happiness, and belongs to me no more. I feel myself dragged towards thee, and it seems to me that thou violently drives me back: Yet are thy looks full of tenderness and goodness.”

Faustus: “Ah! If you know me, come!”

Margaret: “Where shall I go then?”

Faustus: “Thou shalt be free.”

Margaret: “The tomb is without those gates. Death watches my footsteps. Come; but lead me to my everlasting dwelling place. I can go no where but there. Wilt thou leave me? Oh! my love, if I could …”

Faustus: “Thou canst if thou wilt; the gates are open.”

Margaret: “I dare not; no hope remains for me. For what purpose shall I fly? My persecutors are waiting for me. To beg is so miserable. And, above all, with a bad conscience! It is dismal also to wander about in a foreign land; and, besides, wherever I go, they will lay hold on me.”

Faustus: “I will remain near thee.”

Margaret: “Quick, quick, save thy poor child! Go, follow the road by the side of the rivulet, cross the path that leads to the wood; on the left hand, near the sluice, in the fish pond, catch it instantly! It will stretch out its hands to heaven. It seizures with convulsions. Save it! Save it!”

Faust: “Recover thy senses; one step more, and thou hast nothing to fear.”

Margaret: “Had we but passed the mountain! The air is so cold by the side of the spring. There is my mother, sitting on a rock, and her aged head is shaking. She does not call me; she makes no sign to me to approach. Only her eyes are heavy; oh! she will never wake more! We used to be so glad when she slept. Ah! when a recollection!”

Faustus: “Since thou wilt not listen to my entreaties, I must drag thee along in spite of thyself.”

Margaret: “Leave me! No, I will not endure violence; seize me not thus with that murderous strength. Ah! I have only too much done as you would have me!”

Faustus: “The day breaks, my dear love! my dearest love!”

Margaret: “Yes, it will soon be day. My last day dawns upon this dungeon. It comes to celebrate my eternal spousals: tell nobody that you have seen Margaret tonight. Alas, my poor garland. It is withered. We shall meet again, but not on holidays. The crowd is gathering together, oh what a confusion of sounds shall we hear! The streets, the market-place, will hardly be large enough for the multitude. The bell tolls, the signal is given. They are going to tie my hands, to bind my eyes. I shall ascend the bloody scaffold, and the axe’s edge will fall on my neck. Ah! the world is already silent as the grave!”

Faustus: “Heavens! Why was I born?”

Mephistopheles, appearing at the door: “Haste, or you are lost; your delays, your uncertainties, are fatal to you: my horses…”

Margaret: “Who is it that rises out of the earth? It is he, it is he; send him away. What should he have to do in this holy holy place? He means to carry me off with him.”

Faustus: “You must live!”

Margaret: “Tribunal of God! I abandon myself to thee.”

Mephistopheles to Faustus: “Come, come away! or I will leave thee to die together with her.”

Margaret: “Heavenly Father! I am thine; and ye angels, save me! Holy legions, encompass me about, defend me! Faustus, it is thy fate that afflicts me…”

Mephistopheles: “She is judged.”

Voices from Heaven are heard to cry “She is saved!”

Mephistopheles disappears with Faustus. The voice of Margaret is still heard from the bottom of the dungeon, recalling her love in vain. “Faustus! Faustus!”

After these words, the piece is broken off. The intention of the author doubtless is that Margaret should perish, and that God should pardon her; that the life of Faustus should be preserved, but that his soul should be lost.

The imagination must supply the charm which a most exquisite poetry adds to the scenes I have attempted to translate. In the art of versification there is a peculiar merit acknowledged by all the world, and yet independent of the subject to which it is applied. In the play of Faustus, the rhythm changes with the situation, and the billiant variety that results from the change is admirable.

The German language presents a greater number of combinations than ours, and Goethe seems to have employed them all to express, by sounds as well as images, the singular elevation of irony and enthusiasm, of sadness and mirth, which impelled him to the composition of this work. It would indeed be too childish to suppose that such a man was not perfectly aware of all the defects of taste with which his piece was liable to be reproached; but it is curious to know the motives that determined him to leave those defects, or rather intentionally to insert them.

Goethe has submitted himself to rules of no description whatever in this composition; it is neither tragedy nor romance. Its author adjured every sober method of thinking and writing; one might find in it some analogies with Aristophanes, if the traits of Shakespeare’s pathos were not mingled with beauties of a very different nature.

Faustus astonishes, moves, and melts us; but it does not leave a tender impression upon the soul. Though presumption and vice are cruelly punished, the hand of beneficence is not perceived in the administration of the punishment; it would rather be said that the evil principle directed the thunderbolt of vengeance against crimes of which it had itself occasioned the commission; and remorse, such as it is painted in this drama, seems to proceed from hell, in company with guilt.

The belief in evil spirits is to be met with in many pieces of German poetry; the nature of the north agrees very well with this description of terror; it is therefore much less ridiculous in Germany, than it would be in France, to make use of the Devil in works of fiction. To consider all ideas only in a literary point of view, it is certain that our imagination figures to itself something that answers to the conception of an evil genius, whether in the human heart, or in the dispensations of nature.

Man sometimes does evil, as we may say, in a disinterested manner, without end, and even against his end, merely to satisfy a certain inward asperity that urges him to do hurt to others. The deities of paganism were accompanied by a different sort of divinities of the race of the Titans, who presented the revolted forces of nature; and, in Christianity, the evil inclinations of the soul may be said to be personafied under the figure of Devils.

It is impossible to read Faustus without being excited to reflexion in a thousand different manners: We quarrel with the author, we condemn him; we justify him; but he obliges us to think upon everything, and, to borrow the language of a simple sage of former times, upon something more than every thing. (De omnibus rebus et quibusdam aliis.)

The criticisms to which such a production is obnoxious may easily be foreseen, or rather it is the very nature of the work that provokes censure still more than the manner in which it was treated; for such a composition ought to be judged like a dream; and if good taste were always watching at the ivory gate, to oblige our visions to take the regulated form, they would seldom strike the imagination.

Nevertheless, the drams of Faustus is certainly not composed upon a good model. Whether it be considered as an offspring of the delirium of the mind, or of the satiety of reason, it is to be wished that such productions may not be multiplied; but when such a genius as that of Goethe sets itself free from all restrictions, the crowd of thoughts is so great, that on every side they break through and trample down the barriers of art.

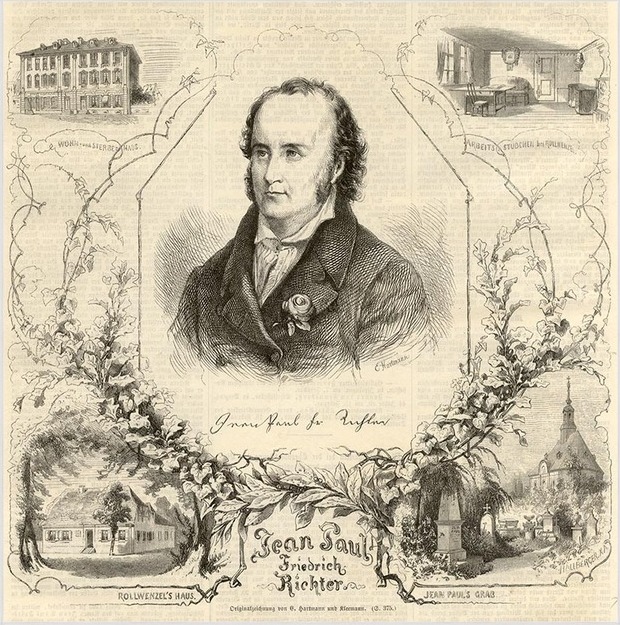

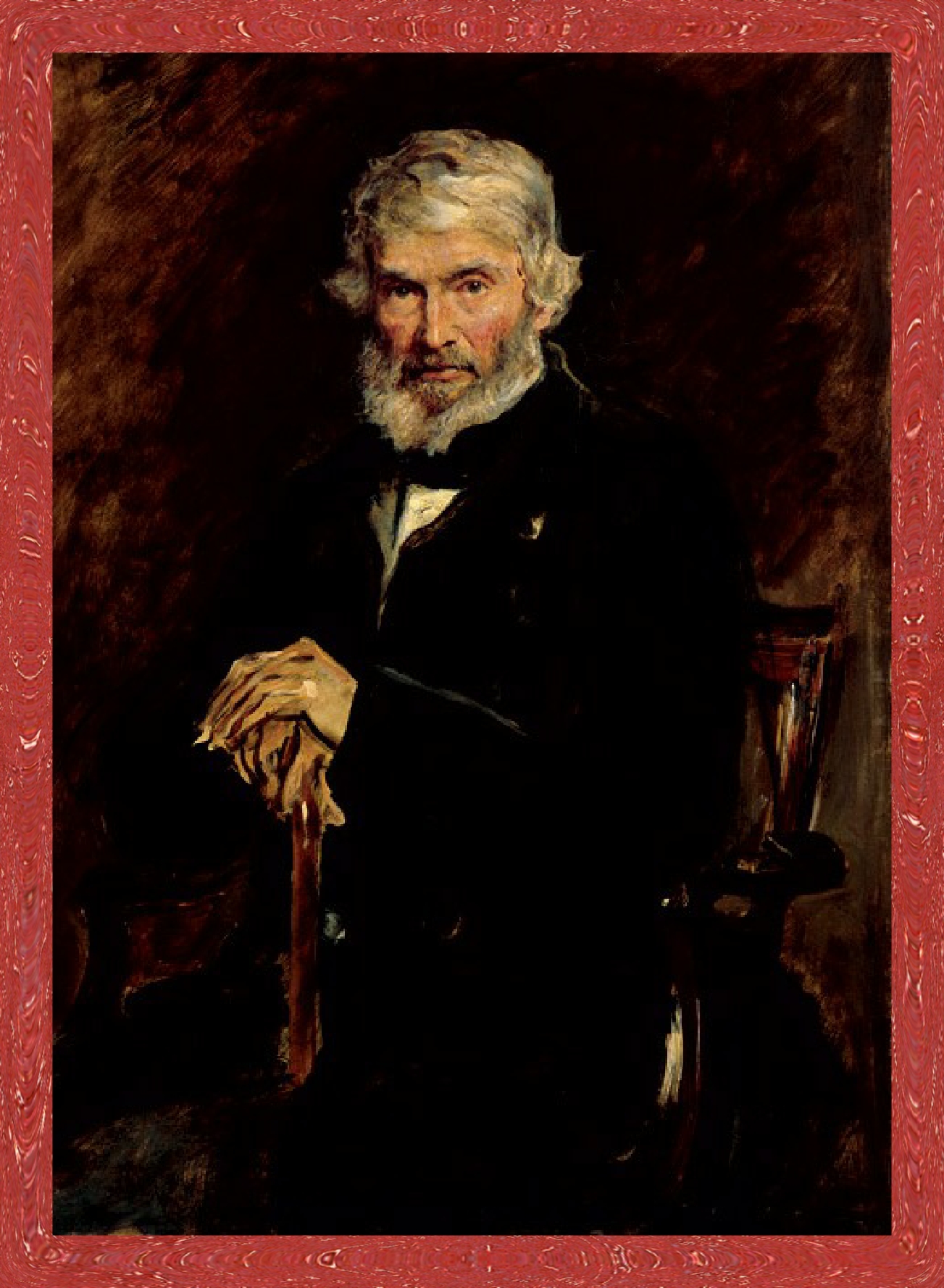

Goethe, 1775-1776

By Georg Melchior Kraus

Madame de Staël: Goethe’s Faust 3

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. II, 203-212. All illustrations by Eugene Delacroix.

“She is not the first!”

The history of Margaret is oppressively painful to the heart. Her low condition, her confined intellect, all that renders her subject to misfortune, without giving her the power of resisting it, inspires us with the greater compassion for her. Goethe, in his novels and in his plays, has scarcely ever bestowed any superior excellence upon his female personages, but he describes with wonderful exactness that character of weakness which renders protection so necessary to them.

Margaret is about to receive Faustus in her house without her mother’s knowledge, and gives this poor woman, by the advice of Mephistopheles, a sleeping draught which she is unable to support, and which causes her death. The guilty Margaret becomes pregnant, her shame is made public, all her neighbours point the finger at her. Disgrace seems to have greater hold upon persons of an elevated rank, and yet it is perhaps more formidable among the lower class. Everything is so plain, so positive, so irreparable, among men who never upon any occasion made use of shades of expression.

Goethe admirably catches those manners. At once so near and so distant from us, he possesses in a supreme degree the art of being perfectly natural in a thousand different natures.

Valentine, a soldier, the brother of Margaret, returns from the wars to visit her, and when he learns her shame, the suffering which he feels, and for which he blushes, betrays itself in language at once harsh and pathetic. A man severe in appearance, yet inwardly endowed with sensibility, causes an unexpected and poignant emotion.

Goethe has painted with admirable truth the courage which a soldier is capable of exerting against moral pain, that new enemy which he perceives within himself, and which he cannot combat with his usual weapons. At last, the necessity of revenge takes possession of him, and brings into action all the feelings by which he was inwardly devoured. He meets Mephistopheles and Faustus at the moment when they are going to give a serenade under his sister’s window. Valentine provokes Faustus, fights with him, and receives a mortal wound. His adversaries fly to avoid the fury of the populace.

Margaret arrives, and asks who lies bleeding upon the earth. The people answer the son of thy mother. And her brother dying addresses to her reproaches more terrible, and more harrowing, than most polished language could ever make use of. The dignity of tragedy could never permit us to dig so deeply into the human heart for the characters of nature.

Mephistopheles obliges Faustus to leave the town, and the despair excited in him by the fate of Margaret creates a new interest in his favor.

“Alas!” he exclaims, “she might so easily have been made happy! a simple cabin in an alpine valley, a few domestic employments, would have been enough to satisfy her limited wishes, and fill up her gentle existence; but I, the enemy of God, could not rest till I had broken her heart, and triumphed in the ruin of her humble destiny. Through me, will peace be for ever ravished from her. She must become the victim of hell. Well! Demon, cut short my anguish, let what must come, come quickly! Be the fate of unhappy creature fulfilled, and cast me headlong, together with her, into the abyss.”

The bitterness and sang-froid of the answer of Mephistopheles are truly diabolical.

“How you enflame yourself,” he says to him, “how you boil!

I know not how to console thee,

and upon my honour

I would now give myself to the Devil if I were not the Devil myself;

but thinkest thou, then, madman,

that because thy weak brain can find no issue,

there is none in reality?

Long live he who knows how to support all things with courage!

I have rendered thee not much unlike myself,

and reflect, I beseech thee,

that there is nothing in the world more disgusting,

than a devil who despairs!”

Margaret goes alone to the church, the only asylum that remains to her: An immense crowd fills the aisles, and the burial service is being performed in this solemn place. Margaret is covered with a veil; she prays fervently; and when she begins to flatter herself with hopes of divine mercy, the evil spirit speaks to her in a low voice, saying,

“Dost thou remember, Margaret, the time when thou came hither to prostrate thyself before the altar? Then wert thou full of innocence, and while thy timid voice lisped the psalms, God reigned in thy heart. Margaret, what hast thou since done? What crimes hast thou committed? Dost thou come to pray for the soul of thy mother, whose death hangs so heavily upon thy head! Dost thou see what blood is that which defiles thy threshold? It is thy brother’s blood. And dost thou not feel stirring in thy womb an unfortunate creature that already forewarns thee of new sufferings?”

Margaret: “Woe! Woe! How can I escape from the thoughts that spring up in my soul and rise in rebellion against me?”

The Choir: (chanting in the church)

Dies irae, dies illa, Solvet saeclum in favilla.

*(The day of wrath will come, and the universe will be reduced to ashes.)

The Evil Spirit: “The anger of Heaven threatens thee, Margaret! The trumpets of the resurrection are sounded; the tombs are shaken, and thy heart is about to awake to eternal flames.”

Margaret: “Ah, that I could fly hence! the sounds of that organ prevent me from breathing, and the chants of the priests penetrate my soul with an emotion that rends it.”

Judex ergo cum sedebit,

Quidquid latet apparebit;

Nil inultum remanebit.

*(When the supreme judge appears, he will discover all that is hidden, and nothing shall remain unpunished.)

Margaret: “It seems as if the walls were closing together to stifle me. Air! Air!”

The Evil Spirit: “Hide thyself! Guilt and shame pursue thee. Thou callest for air and for light; miserable wretch! what hast thou to hope from them?”

Quid sum miser tunc dicturus?

Quem patronum rogaturus?

Cum vix justus sit securus?*

*(Miserable wretch! What then shall I say? to what protector shall I address myself, when even the just can scarcely believe themselves saved?)

The Evil Spirit: “The saints turn away their faces from thy presence; they would blush to stretch forth their pure hands toward thee.”

Quid sum miser tunc dicturus?

Margaret, at this discourse, utters a shriek and faints away.

What a scene! this unfortunate creature who, in the asylum of consolation finds despair; this assembled multiple praying to God with confidence, while the unhappy woman, in the very temple of the Lord, meets the spirit of hell. The severe expressions of the sacred hymn are interpreted by the inflexible malice of the evil genius. What distraction in the heart! what ills accumulated on one poor feeble head! And what a talent his, who knew how to represent to the imagination those moments in which life is lighted up with us like a funeral fire, and throws over our fleeting days the terrible reflection of an eternity of torments!

Mephistopheles conceives the idea of transporting Faustus to the Sabbath of Witches in order to dissipate his melancholy, and this leads us to a scene of which it is impossible to give the idea, though it contains many thoughts which we shall endeavour to recollect: this festival of the Sabbath represents truly the saturnalia of genius. The progress of the piece is suspended by its introduction, and the stronger the situation, the greater we find the difficulty of submitting even to the inventions of genius when they so effectively disturb the interest.

Amidst the whirlwind of all that can be thought or said, when images and ideas rush headlong, confound themselves, and seem to fall back into the abysses from which reason has called them, there comes a scene which reunited us to the circumstances of the performance in a terrible manner. The conjurations of magic cause several different pictures to appear, and all at once Faustus approaches Mephistopheles and says to him:

“Dost thou not see, there below,

a young girl,

pale, though beautiful,

who stands alone in the distance?

She advances slowly,

her feet seem to be knit togehter;

do you not perceive her resemblance to Margaret?”

Mephistopheles: “It is an effect of magic, only illusion. It is not good to dwell upon the sight. Those fixed eyes freeze the blood of men. It was thus that Medusa’s head, of old, turned all who gazed upon it to stone.”

Faustus: “It is true that the eyes of that image are open, like those of a corpse which have not been closed by a friendly hand. There is the bosom on which I rested my head; there are the charms which my heart called its own.”

Mephistopheles: “Madman! all this is but witchcraft; every one thinks he beholds the beloved of his soul in this phantom.”

Faustus: “What madness! What torment! I cannot fly from that look: But what means that red collar that encircles her beautiful neck, no broader than the edge of a knife?”

Mephistopheles: “Tis true; but what would you do? Do not lose thyself thus in thought; ascend this mountain; they are preparing a feast for you on the summit. Come!”

To be continued…

Madame de Staël: Goethe’s Faust 2

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. II, 192-203. Unless otherwise noted, all illustrations by Eugene Delacroix.

This momentary enthusiasm does not continue: Faustus is an inconstant character, the passions of the world recover their hold upon him. He seeks to satisfy them, he wishes to abandon himself to them; and the devil, under the name of Mephistopheles, comes and promises to put him in possession of all the pleasures of the earth, being at the same time able to render him disgusted with them all; for real wickedness so entirely dries up the soul, that it ends by inspiring a profound indifference for pleasures as well as for virtues.

Mephistopheles conducts Faustus to a witch, who keeps under her orders a number of animals, half monkeys and half cats. (Meerkatzen.) This scene may, in some respects, be considered as a parody of that of the witches in Macbeth. The witches in Macbeth sing mysterious words, of which the extraordinary sounds produce at once the effect of magic; Goethe’s witches also pronounce strange syllables, of which the rhythms are curiously multiplied; these syllables excite the imagination to gaiety, by the very singularity of their construction, and the dialogue of this scene, which would be merely burlesque in prose, receives a more elevated character from the charm of poetry.

In listening to the comical language of these cat-monkeys, we think we discover what would be the ideas of animals if they were able to express them, what a coarse and ridiculous image they would represent to themselves, of nature, and of mankind.

The French stage has scarcely any specimens of these pleasantries founded on the marvelous, on prodigies, witchcrafts, transformations, &c: this is to make sport with nature, as in comedies we make sport with men. But, to derive pleasure from this sort of comedy, reason must be set aside, and the pleasures of the imagination must be considered as a licensed game, without any object. Yet is this game not the more easy on that account, for restrictions are often supports; and when, in the career of literature, men give scope to boundless invention, nothing but the excess, the very extravagance, of genius, can confer any merit on these productions; the union of wildness with mediocrity would be intolerable.

Mephistopheles conducts Faustus into the company of young persons of all classes, and subdues, by different means, the different minds with which he engages. He effects his conquests over them, not by admiration, but by astonishment. He always captivates by something, unexpected and contemptuous in his words and actions; for vulgar spirits, for the most part, take so much the more account of a superior intellect, as that intellect appears to be indifferent about them. A secret instinct tells them that he who despises them sees justly.

A Leipsic student, who has just left his mother’s house, as simple as one can be at that age in the good country of Germany, comes to consult Faustus about his studies; Faustus begs Mephistopheles to take on himself the charge of answering him. He puts on a doctor’s gown, and while waiting for the scholar, expressed, in a soliloquy, his contempt for Faustus. “This man,” says he, “will never be more than half wicked, and it is in vain that he flatters himself with the hope of becoming completely so.”

It is so in fact; whenever people naturally well principled turn aside from the plain road, they find themselves shackled by a sort of awkwardness that proceeds from uncontrollable remorse, while men who are radically bad make a mock of those candidates, for vice who, with the best intention to do evil, are without talent to accomplish it.

At last the scholar presents himself, and nothing can be more naive than the awkward and yet presumptuous eagerness of this young German, on his entrance for the first time in his life into a great city, disposed of all things, knowing nothing, afraid of every thing he sees, yet impatient to possess it, desirous of information, eagerly wishing for amusement, and advancing with an artless smile towards Mephistopheles, who receives him with a cold and contemptuous air; the contrast between the unaffected good humour of the one, and the disdainful insolence of the other, is admirably lively.

There is not a single branch of knowledge but the scholar desires to become acquainted with it; and what he desires to learn, he says, is science and nature. Mephistopheles congratulates him on the precision with which he has marked out his plan of study. He amuses himself by describing the four faculties, law, medicine, philosophy, and theology, in such a manner, as to confound the poor scholar’s head for ever. Mephistopheles makes a thousand different arguments for him, all which the scholar approves one after the other, but the conclusion of which astonishes him, because he looks for serious discourse while the devil is only laughing at every subject.

The scholar comes prepared for general admiration, and the result of all he hears is only universal contempt. Mephistopheles agrees with him that doubt proceeds from hell, and that the devils are those who deny; but he expresses doubt itself with a tone of decision, which, mixing arrogance of character with uncertainty of reasoning, leaves no consistency in any thing, but evil inclinations. No belief, no opinion, remains fixed in the head after having listened to Mephistopheles; and we feel disposed to examine ourselves in order to know whether there is any truth in the world, or whether we think only to make a mock of those who fancy that they think.

“Must not every word have an idea annexed to it?” says the scholar. “Yes, if it can,” replies Mephistopheles,” but we need not trouble ourselves too much about that, for where ideas are wanting, words come on purpose to supply the place of them.”

Sometimes the scholar cannot comprehend Mephistopheles, but he has only so much the more respect for his genius. Before he takes leave of him, he begs him to inscribe a few lines in his album, the book in which, according to the German way, every one makes his friends furnish him with a mark of their remembrances. Mephistopheles writes the words that Satan spoke to Eve, to induce her to eat the fruit of the tree of life. “Thou shalt be as God, knowing good and evil.”

“I may well,” says he to himself, “borrow this ancient sentence of my cousin the serpent, they have long made use of it in my family.” The scholar takes back his book, and goes away perfectly satisfied.

Faustus grows tired, and Mephistopheles advises him to fall in love. He becomes actually so with a young girl of the lower class, extremely innocent and simple, who lives in poverty with her aged mother. Mephistopheles, for the purpose of introducing Faustus to her, takes it into his head to form an acquaintance with one of her neighbors, named Martha, whom the young Margaret sometimes goes to visit. This woman’s husband is abroad, and she is distracted at receiving no news of him; she would be greatly afflicted at his death, yet at least she would wish not to be left in doubt of it; and Mephistopheles greatly softens her grief, by promising her an obituary account of her husband, in regular form, for her to publish in the gazette according to custom.

Poor Margaret is delivered up to the power of evil; the infernal spirit lets loose all his malaice upon her; and renders her culpable, without depriving her of that rectitude of heart which can find repose only in virtue. A dexterous villain takes care not wholly to pervert those honest people whom he designs to govern; for his ascendancy over them depends upon the alternate agitations of crime and remorse. Faustus, by the assistance of Mephistopheles, seduces this young girl, who is remarkably simple both in mind and soul. She is pious, though culpable; and when alone with Faustus, asks him whether he has any religion. “My child,” says he, “you know I love you. I would give my blood, and my life for you; I would disturb the faith of no one. Is not this all that you can desire?”

Margaret: “No, it is necessary to believe.”

Faustus: “Is it necessary?”

Margaret: “Ah! that I had any influence over you! you do not sufficiently reverence the holy sacraments.”

Faustus: “I do reverence them.”

Margaret: “But without ever drawing near them, it is long since you have confessed yourself, long since you have been at mass: do you believe in God?”

Faustus: “My dear friend, who dares to say, I believe in God? If you propose this question to priests and sages, they will answer as if they intended to mock him who questions them.”

Margaret: “So, then, you believe nothing.”

Faustus: “Do not construe my words so ill, charming creature! Who can name the Deity and say, I comprehend him? Who can feel, and not believe in him? Does not that which supports the universe embrace thee, me, and universal nature? Does not Heaven descend to form a canopy over our heads? Is not the earth immovable under our feet? Do not the eternal stars, from their spheres on high, look down upon us with love? Are not thine eyes reflected in mine, melting with tenderness? Does not an eternal mystery, visible and invisible, attract my heart to thine? Let they soul be filled with this mystery, and when you experience the supreme happiness of feeling, call that happiness thy heart, love, God; it is all the same. Feeling is all in all, names are but an empty sound, a vain smoke, that darkens the splendour of Heaven.”

This morsel of inspired eloquence would not suit the character o f Faustus, if at this moment he were not better, because he loves; and if the intention of the author had not doubtless been to shew the necessity of a firm and positive belief, since even those whom Nature has created good and kind, are not the less capable of the most fatal aberrations when this support is wanting to them.

Faustus grows tired of the love of Margaret, as of all the enjoyments of life; nothing is finer, in the original, than the verse in which he expresses at once the enthusiasm of science and the satiety of happiness.

Faustus: “Sublime spirit! Thou hast granted me all that I have asked of thee. It is not in vain that thou hast turned towards me thy countenance encircled with flames; thou has given me magical nature for my empire; thou hast given me strength to feel and enjoy it. Thou hast given me not coldly to admire, but inwardly to be acquainted with; thou hast given me to penetrate into the bosom of the universe as into that of a friend; thou hast brought before me the varied assembly of living things, and hast taught me to know my breathen in the inhabitants of the woods, the air, and the waters.

When the tempest howls in the forest, when it uproots and subverts the gigantic pines, and makes the mountain re-echo to their fall, thou guidest me into a safe asylum, and thou revealest to me the secret wonders of my own heart. When the calm moon silently ascends the sky, the silvered shades of ancient times glide before my eyes over the rocks and in the woods, and seem to soften for me the severe pleasure of meditation.

But, alas! I feel it, man can attain perfection in nothing; by the side of those delights which bring me near to the gods, I am doomed to support that cold, that indifferent, that haughty companion, who humbles me in my own eyes, and by a word reduces to nothing, all the gifts that thou has bestowed upon me. He kindles in my bosom an untameable fire that urges me to the pursuit of beauty; I pass, in delirium, from desire to enjoyment; but in the very bosom of happiness a vague sensation of satiety causes me to regret the restlessness of desire.”

To be continued…

Scenes from Faust by Moritz Retzsch

Madame de Staël: Goethe’s Faust

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. II, 181-192. Unless otherwise noted, all illustrations by Eugene Delacroix.

“Faustus”

Plan all things to achieve my end!

Engage the attention of her friend!

No milk and water devil be.

And bring fresh jewels instantly!

Among the pieces written for the performance of puppets, there is one entitled “Dr. Faustus, or Fatal Science,” which has always had great success in Germany. Lessing took up this subject fore Goethe. This wonderful history is a tradition very generally known. Several English authors have written the life of this same Dr. Faustus, and some of them have even attributed to him the art of printing — his profound knowledge did not preserve him from being weary of life, and in order to escape from it, he tried to enter into a compact with the devil, who concludes the whole by carrying him off. From these slender materials, Goethe has furnished the astonishing work, of which I will now try to give some idea.

Certainly, we must not expect to find in its either taste, or measure, or the art that selects and terminates; but if the imagination could figure to itself an intellectual chaos, such as the material chaos has often been painted, the “Faustus” of Goethe should have been composed at that epoch. It cannot be exceeded in boldness of conception, and the recollection of this production is always attended with a sensation of giddiness.

The Devil is the hero of the piece;

the author has not conceived him like a hideous phantom,

such as he is usually represented to children;

he has made him, if we may so express ourselves,

the evil Being par excellence,

before whom all others…are only novices,

scarcely worthy to be the servants of Mephistopheles.

Goethe wished to display in this character, at once real and fanciful, the bitterest pleasantry that contempt can inspire, and at the same time an audacious gaiety that amuses. There is an infernal irony in the discourses of Mephistopheles, which extends itself to the whole creation, and criticizes the universe like a bad book of which the Devil has made himself the censor.

Mephistopheles makes sport with genius itself, as with the most ridiculous of all absurdities, when it leads men to take a serious interest in any thing that exists in the world, and above all when it gives them confidence in their own individual strength. It is singular that supreme wickedness and divine wisdom coincide in this respect; that they equally recognize the vanity and weakness of all earthly things: but the one proclaims this truth only to disgust men with what is good, the other only to elevate them above what is evil.

If the play of “Faustus” contained only a lively and philosophical pleasantry, an analogous spirit may be found in many of Voltaire’s writings; but we perceive in this piece an imagination of a very different nature. It is not only that it displays to us the moral world, such as it is, annihilated, but that Hell itself is substituted in the room of it. There is a potency of sorcery, a poetry belonging to the principle of evil, a delirium of wickedness, a distraction of thought, which make us shudder, laugh and cry, in a breath.

It seems as if the government of the world were, for a moment, entrusted to the hands of the Demon. You tremble because he is pitiless, you laugh because he humbles the satisfaction of self-love, you weep, because human nature, thus contemplated from the depths of hell, inspires a painful compassion.

Milton has drawn his Satan larger than man; Michaelangelo and Dante have given him the hideous figure of the brute combined with the human shape. The Mephistopheles of Goethe is a civilized Devil. He handles with dexterity that ridicule, so trifling in appearance, which is nevertheless often found to consist with a profundity of malice; he treats all sensibility as silliness or affectation; his figure is ugly, low, and crooked; he is awkward without timidity, disdainful without pride; he affects something of tenderness with the women, because it is only in their company that he needs to deceive, in order to seduce; and what he understands by seduction, is to minister to the passion of others; for he cannot even imitate love. This is the only dissimulation that is impossible to him.

The character of Mephistopheles supposes an inexhaustible knowledge of social life, of nature, and of the marvelous. This play of “Faustus,” is the nightmare of the imagination, but is is a nightmare that redoubles its strength. It discovers the diabolical revelation of incredulity — of that incredulity which attaches itself to everything that can ever exist of good in this world; and perhaps this might be a dangerous revelation, if the circumstances produced by the perfidious intentions of Mephistopheles did not inspire a horror of his arrogant language, and make known the wickedness which it covers.

In the character of Faustus, all the weaknesses of humanity are concentrated: desire of knowledge, and fatigue of labour; wish of success and satiety of pleasure. It presents a perfect model of the changeful and versatile being whose sentiments are yet more ephemeral than the short existence of which he complains. Faustus has more ambition than strength; and this inward agitation produces his revolt against nature, and makes him have recourse to all manner of sorceries, in order to escape from the hard but necessary conditions imposed upon mortality.

He is discovered, in the first scene, surrounded by his books, and by an infinite number of mathematical instruments and chemical phials. His father had also devoted himself to science, and transmitted to him the same taste and habits. A solitary lamp enlightens this gloomy retreat, and Faustus pursues without intermission his studies of nature, and particularly of magic, many secrets of which are already in his possession.

Rembrandt’s Faust

He invokes one of the creating Genii of the second order; the spirit appears, and counsels him not to elevate himself above the sphere of the human understanding — “It is for us,” he says, “it is for us to plunge into the tumult of exertion, into those eternal billows of life, which are made to swell and sink, are impelled and recalled, by man’s nativity and dissolution: we are created to labour in the work which God has ordained us, and of which time completes the web. But thou, who canst conceive of nothing beyond thine own being, thou, who trembles to sound thine own destiny, and whom a breath of mine makes sudden, leave me! Recall me no more!” When the Genii has disappeared, a deep despair seizes on Faustus, and he forms the design of poisoning himself.

“And I,” he says, ” the image of the Deity, I, who believed myself on the point of tasting eternal truth in all the splendour of celestial light! I, who was no longer a son of the earth, who felt myself equal to the cherubim, who creators in their turn, are susceptible of the enjoyments of God himself! Ah! how much do I need expiate my presumptuous anticipation! One word of thunder has dissipated them for ever. Divine spirit! I had power to attract, but none to retain thee, I felt myself at once so great and so little! But thou hast driven me back, with violence, to the uncertain lot of humanity!

Who now will instruct me? What ought I to avoid? Ought I to yield to the impulse which presses upon me? Our action, as our sufferings, arrest the advance of thought. Low inclinations oppose themselves to the most magnificent conception of the soul. When we attain a certain degree of sublime happiness, we treat as illusion and falsehood whatever is more valuable than this happiness; and the sublime sentiments with which we were gifted by the Creator, lose themselves in earthly interests.

At first, imagination, with its daring wings, aspires to eternity; soon a little space is enough for the ruins of our broken hopes. Anxiety takes possession of our heart. She engenders secret griefs within it, and robs it of pleasure and repose. She presents herself to us in a thousand shapes; now under the aspect of fortune, then as a wife or children, in the likeness of the dagger, of poison, of flames, or of the ocean, she pursues and harasses us. Man trembles in the contemplation of what never will happen, and mourns incessantly for what he has never lost.

No, I did not compose myself to the Deity; no, I feel my misery: it is the insect that I resemble; the insect that agitates the dust on which it exists, and is crushed by the foot of the passenger.

And what, but dust, are all these books by which I am surrounded? Am I not shut up in the prison of science? These walls, these windows which environ me, do they suffer even the light of the sun to reach me without altering its rays? What am I to do with these numberless volumes, with these endless nothings that crowd my brain? Shall I find among them what I want? If I cast my eye over these pages, what shall I read into them? That men everywhere torment themselves about their fate; that from time to time a single happy man has existed, and that he has made all the other inhabitants of the earth despair.” (A death’s head is on the table.)

“And thou, who seemest to address me with that horrible grin, was not the mind that once inhabited thy brain guilty of error like my own? Did it not search for light, and did it not sink under the weight of darkness? These instruments of every description, that my father collected, to assist him in his vain labours; these wheels, and cylinders, and levers, will they reveal to me the secret of nature? no, she is involved in mystery, for all that she pretends to display herself on the light; and, what she chooses to conceal, not all the efforts of science will ever tear from her bosom.

My ears turn themselves, then, to thee, thou poisoned beverage! Thou, who bestowest death, I salute thee like a pale ray of light in the gloomy forest. In thee, I honour science and reverence the human understanding. Thou art the sweetest essence of all sleeping juices. In thee are concentrated all the powers of death. Come to my relief! I feel my troubled spirit already grow calm; I am about to launch upon the open sea. The limpid waves glitter like a mirror under my feet. A new day invitest me to the opposite shore. A chariot of fire already hovers over my head; I am about to ascend it; soon shall I wander amongst etherial spheres, and taste the delights of the heavenly regions.

But how deserve them in this state of my debasement? Yes, I may deserve them if I dare, if I courageously burst those gates of death before which no man can pass without shuddering. It is time to display the dignity of man. I must no longer shiver on the brink of this abyss, where the imagination condemns itself to its own torments, and the flames of hell seem to prohibit our approach. Into this cup of pure crystal will I pour the mortal poison. Alas! it once served for another use: it circulated from hand to hand in the joyous festivals of our fathers, and the guest, as it passed to him, celebrates its beauty in a song.

Thou gilded cup! Thou bringest to my remembrance the jovial nights of my youth. No more shall I pass thee to my neighbour; no more shall I extol the artist that fashioned and embelished thee. Thou art now filled with a dismal beverage — it was prepared by me, it is chosen by me. Ah! be it for me the solemn libation which I consecrate to the morning of a new existence!”

At the moment when he is about to swallow the poison, Faustus hears the town bells ringing in honour of Easter day, and the choirs of the neighboring church celebrating that holy feast.

The Choir: “Christ is risen. Let degenerate, weak and trembling mortals be glad thereof!”

Faustus: “With what imposing solemnity does this brazen sound shake my soul to its very foundations! What pure voices are those that make the poisoned cup fall out of my hand? Do yet announce, resounding bells, the first hour of the sacred sabbath of Easter? Ye, oh choir! do ye already celebrate those strains of consolation, those strains, which, in the night of the grave, were sung by angels descending from heaven to commence the new covenant?”

The choir repeats: “Christ is risen….”

Faustus: “Celestial strains! potent and gentle, wherefore do ye seek me, humbled in the dust? Go! make yourselves heard by those who are capable of deriving comfort from you! I hear the message you convey to me, but I want faith to believe it. Miracle is the cherished offspring of faith. I cannot spring upwards to the sphere from which your glorious tidings are descending: and yet, accustomed from childhood to these songs, they recall me to life. Once, a ray of divine light used to call on me during the peacful solemnity of the sabbath. The drowsy hum of the bells used to fill my soul with the presentiment of futurity, and prayer was an ardent enjoyment to my heart.

Those same bells also announced the games of youth, and the festival of spring. The memory of them rekindles those feelings of childhood which remove us from the contemplation of death. Oh! should again, celestial strains! Earth has regained possession of me.”

To be continued…

Madame de Staël: Goethe – Part 1 of 3

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. I, 265-272