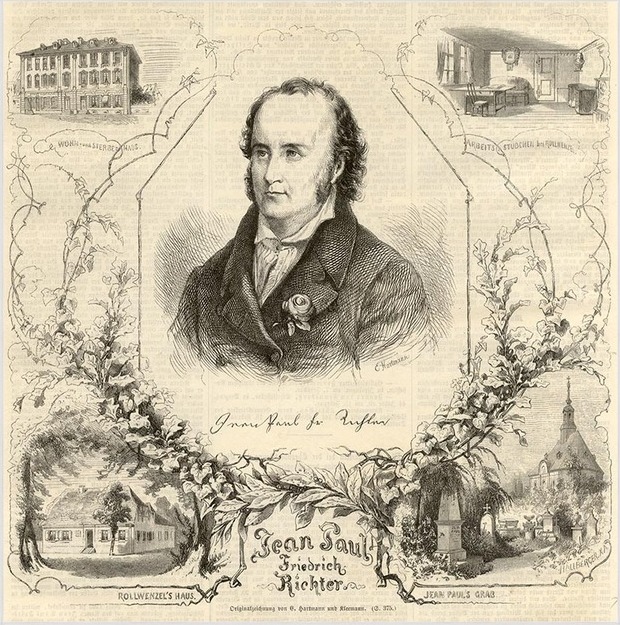

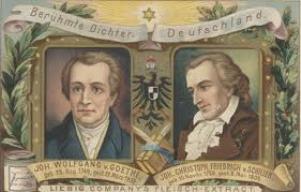

Madame de Staël: Goethe’s Egmont 1/2

Excerpt from DE L’ALLEMAGNE – “Germany” by Madame Germaine de Staél-Holstein (published 1810, the 1813 John Murray translation), Vol. III, 146-153.

If my Life was a mirror in which thou

Did love to contemplate thyself,

So be also my death.

Men are not together only

When in each other’s presence;

The distant, the departed,

Also live for us.

I shall live for thee,

And for myself,

I have lived long enough.

“The Count of Egmont” appears to me the finest of Goethe’s tragedies; he wrote it, I believe, at the same time, when he composed Werther; the same warmth of soul is alike in both. The play begins at the moment when Philip II, weary of the mild government of Margaret of Parma, in the Low Countries, sends the Duke of Alva to supply her place.

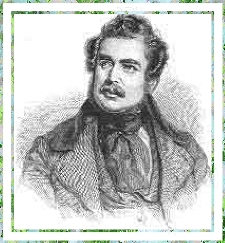

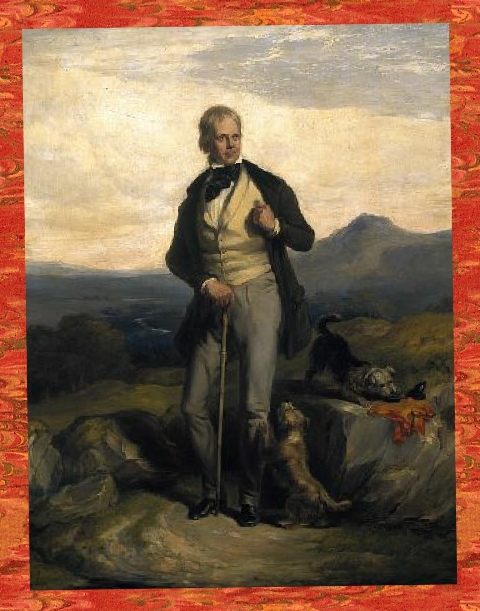

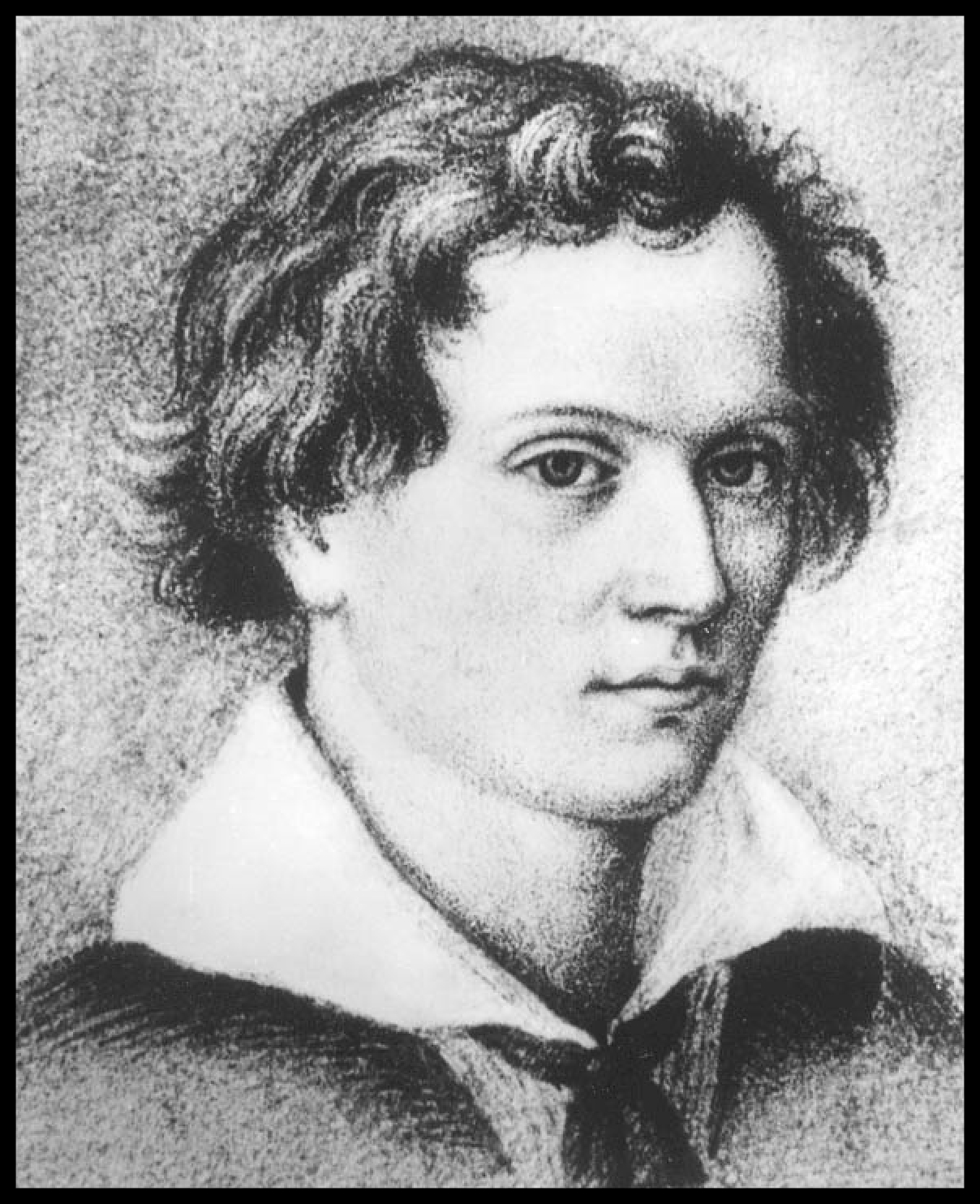

William of Orange

The king is troubled by the popularity which the Prince of Orange and the Count of Egmont have acquired; he suspects them of secretly favouring the partizans of the reformation. Every thing is brought together that can furnish the most attractive idea of the Count of Egmont; he is seen adored by the soldiers at the head of whom he has borne away so many victories.

The Spanish princess trusts his fidelity, even though she knows how much he censures the severity that has been employed against the Protestants. The citizens of Brussels look on him as the defender of their liberties before the throne; and to complete the picture, the Prince of Orange, whose profound policy and silent wisdom are so well known in history sets off still more the generous imprudence of Egmont, in vainly entreating him to depart with himself before the arrival of the Duke of Alva. The Prince of Orange is a wise and noble character; an heroic but inconsiderate self-devotion can alone resist his counsels.

The Count of Egmont resolves not to abandon the inhabitants of Brussels; he trusts himself to his fate, because his victories have taught him to reckon upon the favours of fortune, and he always preserves in public business the same qualities that have thrown so much brilliancy over his military character.

Egmont, on the contrary,

Advances with a bold step,

As if the world were all his own.

These noble and dangerous qualities interest us in his destiny; we feel on his account fears which his intrepid soul never allowed him to experience for himself; the general effect of his character is displayed with great art in the impression which it is made to produce on all the different persons by whom he is surrounded. It is easy to trace a lively portrait of the hero of a piece; it requires more talent to make him known by the admiration that he inspires in his soldiers, the people, the great nobility, in all that bear any relation to him.

The Count of Egmont is in love with a young girl, Clara, born in the class of citizens at Brussels; he goes to visit her in her obscure retreat. This love has a larger place in the heart of the young girl than in his own; the imagination of Clara is entirely subdued by the lustre of the Count of Egmont, by the dazzling impression of his heroic valour and brilliant reputation.

There are goodness and gentleness in the love of Egmont; in the society of this young person he find repose from trouble and solicitude. “They speak to you,” he said, “of this Egmont, silent, severe, authoritative; who is made to struggle with events and with mankind; but he who is simple, loving, confiding, happy, that Egmont, Clara, is thine.”

The love of Egmont for Clara would not be sufficient for the interest of the piece; but when misfortunate is joined to it, this sentiment which before appeared only in the distance, acquires an admirable strength.

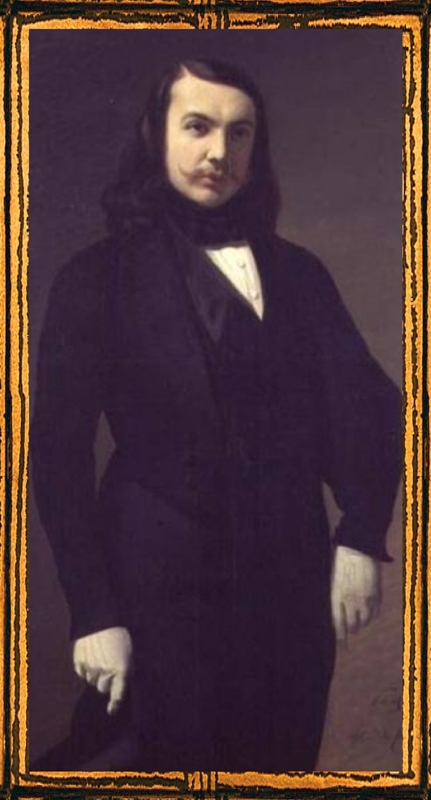

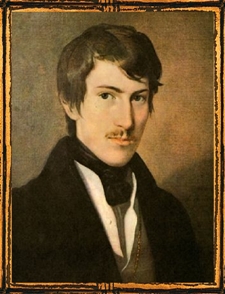

Duke of Alva

The arrival of the Spaniards with the Duke of Alva at their head being made known, the terror spread by that gloomy nation amongst the joyous people of Brussels is described in a superior manner. At the approach of a violent storm, men retire to their houses, animals tremble, birds take a low flight, and seem to seek an asylum in the earth — all nature seems to prepare itself to meet the scourge which threatens it — thus terror possessed the minds of the unfortunate inhabitants of Flanders. The Duke of Alva is not willing to have the Count of Egmont arrested in the streets of Brussels, he fears an insurrection of the people, and wishes if possible to draw his victim to his own palace, which commands the city, and adjoins the citadel.

The matter turns upon a single point:

He would have me live as I cannot.

He employs his own son, young Ferdinand, to prevail on the man he wishes to ruin, to enter his abode. Ferdinand is an enthusiastic admirer of the hero of Flanders, he has no suspicion of the horrid designs of his father, and displays a warmth and ardour of character which persuades the Count of Egmont that the father of such a son cannot be his enemy. Egmont consents to accompany him to the Duke of Alva. That perfidious and faithful representative of Phillip II expects him with an impatience which makes one shudder. He places himself at the window, and perceives him at a distance, mounted on a superb horse, which he had taken in one of his victorious battles.

The Duke of Alva feels a cruel and increasing joy at every step which Egmont makes towards his palace. When the horse stops, he is agitated; his guilty heart pants to effect his criminal purpose, and when Egmont enters the court he cries: “One foot is in the tomb, another step! the grated entrance closes on him, and now! he is mine!”

The Count of Egmont having entered, the Duke discourses with him for some time on the government of the Low Countries, and on the necessity of employing rigour to restrain the progress of the new opinions. He has no longer any interest in deceiving Egmont, and yet he feels a pleasure in the success of his craftiness, and wishes still to enjoy it a few moments. At length, he rouses the generous soul of Egmont and irritates him by disputation in order to draw from him some violent expressions.

He affects to be provoked by them, and performs, as by a sudden impulse, what he had calculated on and determined to do long before. Why so many precautions with a man who is already in his power, and whom he has determined to deprive, in a few hours, of existence? It is because the political assassin always retains a confused desire to justify himself, even in the eye of his victim. He wishes to say something in his excuse even when all he can allege persuades neither himself nor any other person.

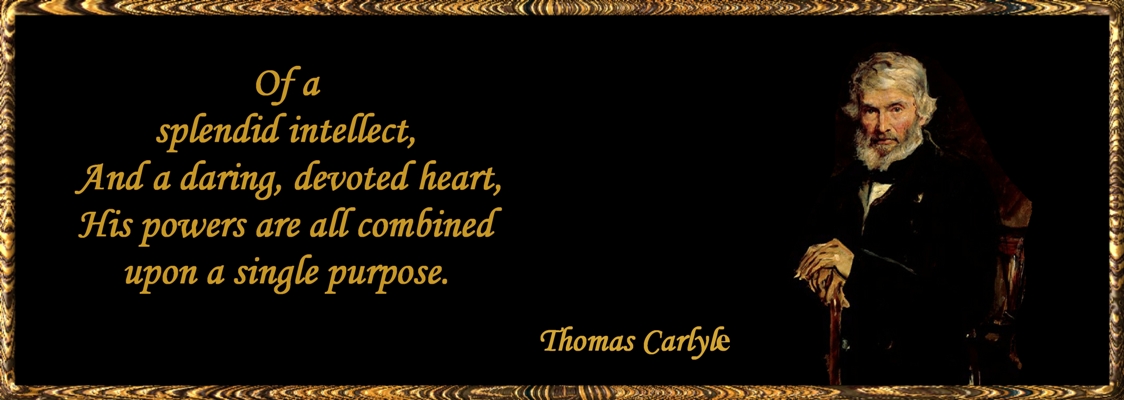

Perhaps no man is capable of entering on a criminal act without some subterfuge, and therefore the true morality of dramatic works consists not in poetical justice which the author dispenses as he thinks fit, and of which history so often shews us the fallacy, but in the art of painting vice and virtue in such colours as to inspire us with hatred to the one and love to the other.

The report of the Count of Egmont’s arrest was scarcely spread through Brussels before it is known that he must perish. No one expects that justice will be heard. His terrified adherents ventured not a word in his defense, and suspicion soon separates those whom the same interest had united. An apparent submission arises from the terror which every individual feels and inspires in his turn, and the panic which pervades them all, that popular cowardice which so quickly succeeds a state of unusual exaltation, is in this part of the work most admirably described.

Clara alone, that timid girl who scarcely ever ventured to leave her own abode, appears in the public square at Brussels, reassembles by her cries the citizens who had dispersed, recalls to their recollection the enthusiasm which the name of Egmont had inspired, the oath they had taken to die for him. All who heard her shudder! “Young woman,” says a citizen of Brussels; “speak not of Egmont, his name is fatal to us.”

“What! Shall I not pronounce his name?” cried Clara. “Have you not all invoked it a thousand times? Is it not written on every thing around us? Have I not seen its brilliant character traced even by the stars of Heaven? Shall I not then name it? Worthy people! What are you about? Is your mind perplexed, your reason lost? Look not upon me with that unquiet and apprehensive air. Cast not down your eyes in terror.

What I demand is also what you yourselves desire. Is not my voice the voice of your own heart? Ask of each other, which of you will not this very night prostrate himself before God to beg the life of Egmont? Which of you in his own house will not repeat, ‘The liberty of Egmont, or death?'”

To be continued …

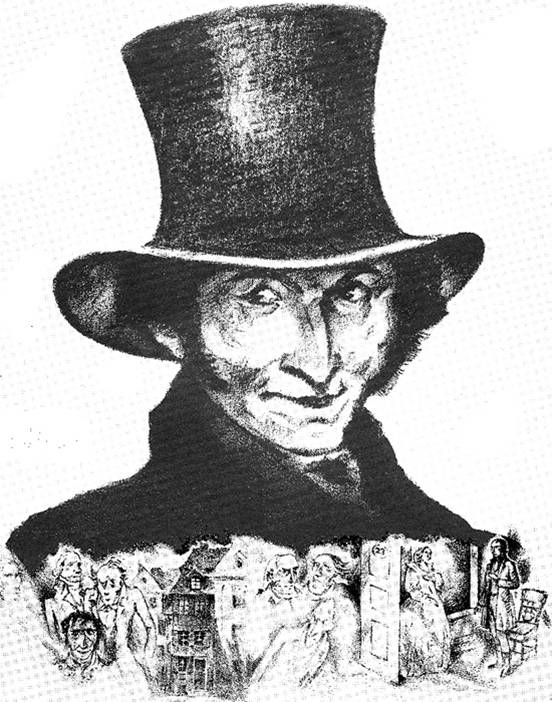

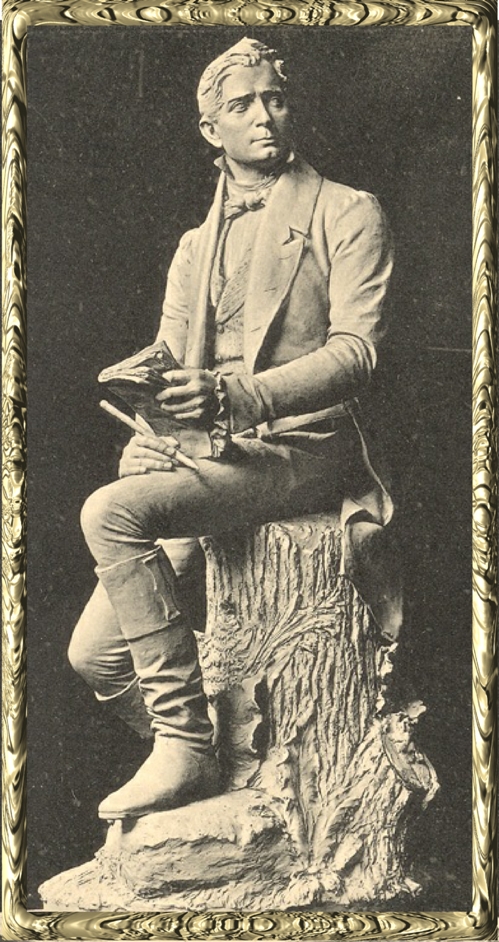

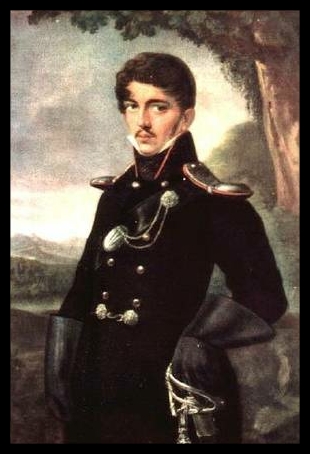

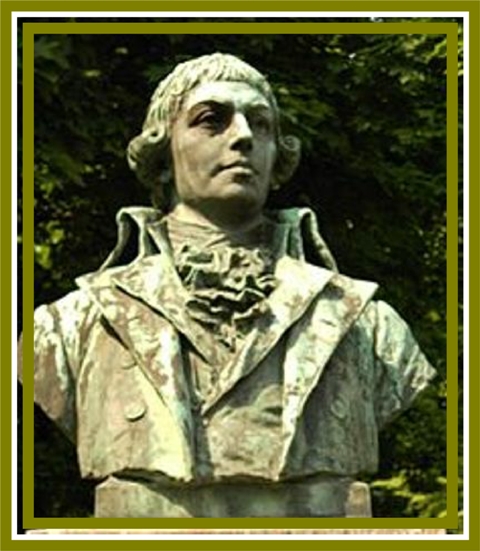

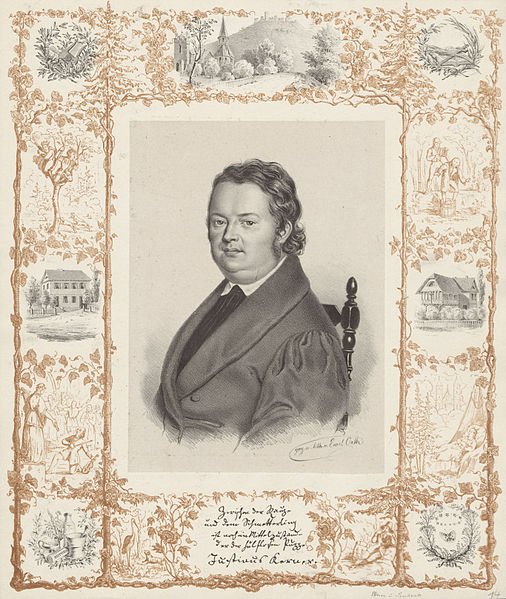

Lamoral, Count of Egmont, Prince of Gavre

1522-1568

From an 1888 Engraving