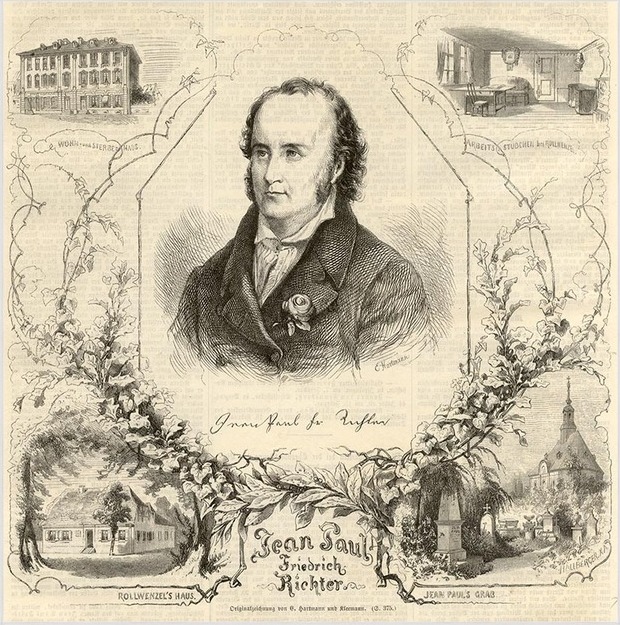

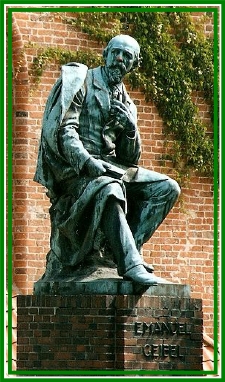

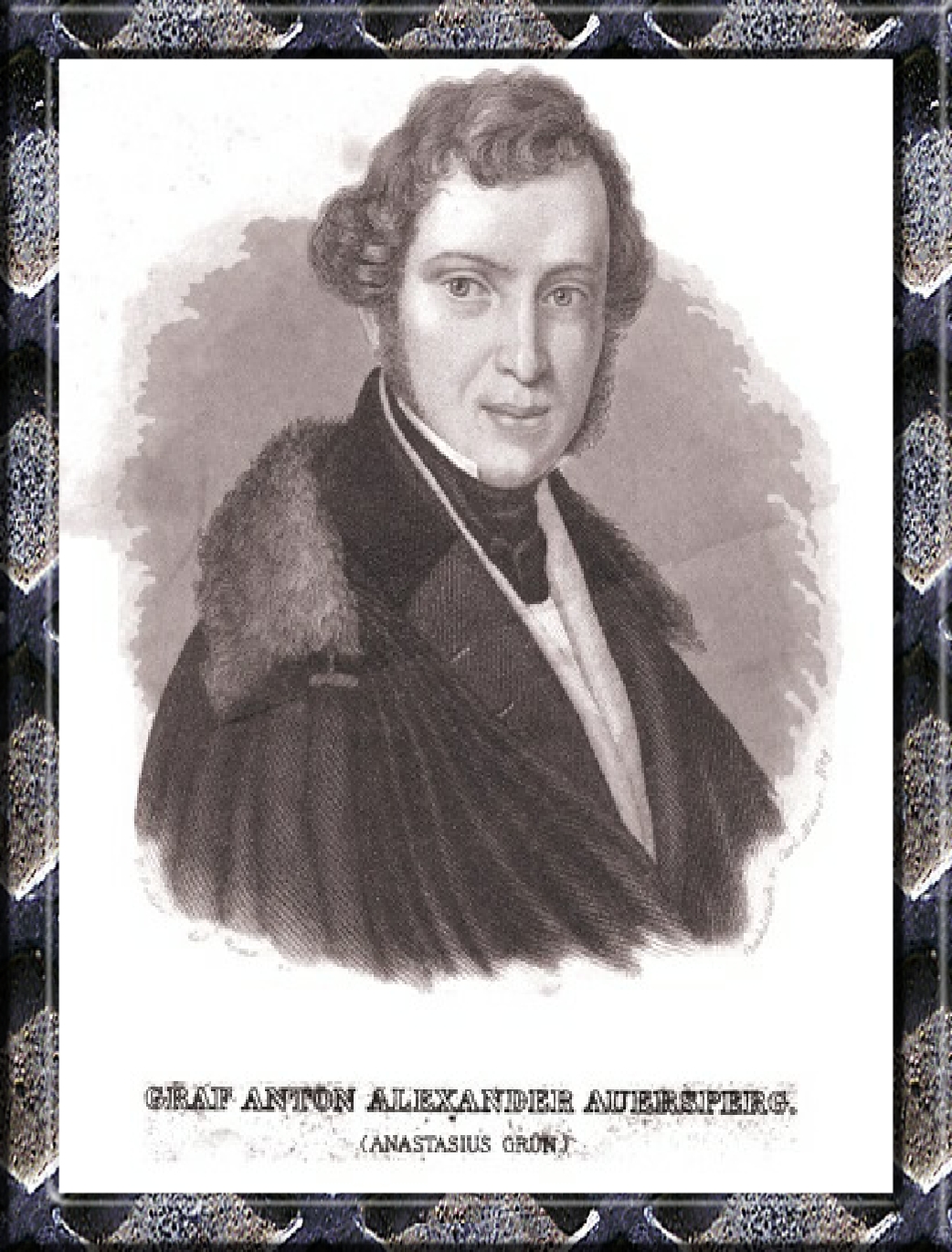

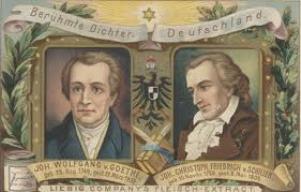

Jean Paul’s “Titan” Pt. 2

Excerpt, “Titan: A Romance” from the German of Jean Paul Friedrich Richter. Translated by Charles T. Brooks in two volumes, Vol. II. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1862.

The Torches of

Castello Aragonese

With emotion, with a sort of festive solemnity, Albano trod the cool island. It was to him as if the breezes were always wafting to him the words, “The place of rest.” Agata begged them both to stay with her parents, not far from the Borgho d’Ischia. As they went over the bridge, which connects the green rock wound round with houses to the shore and the city, she pointed out to them joyfully in the east the individual house.

As they walked along so slowly, and the high round rock and the row of houses stood mirrored in the water; and upon the flat roofs the beautiful women who were trimming the festal lamps for the evening spoke busily over to each other, and greeted and questioned the returning Agata. All faces were so glad, all forms so comely, and the poorest in silk. The lively boys pulled down little chestnut tops; and the old father of the isle, the tall Epomeo, stood before them all clad in vine-foliage and spring-flowers, out of whose sweet green only scattered white pleasure-houses of happy mountain-dwellers peeped forth.

Then was it to Albano as if the heavy pack of life had fallen off from his shoulders into the water, and the erect bosom drank in from afar the cool ether flowing in from Elysium. Across the sea lay the former stormy world, with its hot coasts.

Agata led the two into the home of her parents, on the Eastern declivity of Epomeo; and immediately, amidst the wild exulting welcome cried out, quite as loudly, “Here are two fine gentleman who wish to come home with me!” The father said directly, “Welcome, your excellencies!” Agata showed him the way to his cool chamber, and he went up.

Here, before the cooling sea-zephyr, the going to sleep was indeed the slumber, and the echoing dream itself the sleep. His dream was an incessant song, which sang itself: “The morning is a rose, the day the tulip, night is a lily, and the evening is another morning.”

He dreamed himself at last down into a deep sleep. Late, in the dark, like an Adam in renovated youth, he opened his eyes in Paradise, but he knew not where he was. He heard distant sweet music; unknown flower scents swam through the air. He looked out; the dark heaven was strewed with golden stars, as with fiery blossoms; on the earth, on the sea hovered hosts of lights; and in the depths of distance hung a clear flame steadily in the midst of heaven. A dream, of which the scene was unknown, confounded still the actual stage with one that had vanished; and Albano went through the silent, unpeopled house, dreaming on, out into the open air, as into an island of spirits.

Here, nightingales, first of all, with their melody drew him into the world. He found the name Ischia again, and saw now that the castle on the rock and the long street of roofs in the shore town full of burning lamps. He went up to the place whence the music proceeded, which was illuminated and surrounded with people, and found a chapel standing all in fires of joy. Before a Madonna and her child, in a niche, a night-music was playing, amidst the loquacious rustling of joy and devotion. Here, he found his hosts, who had all quite forgotten him in the jubilee; and Dian said, “I would have awakened you soon; the night and the pleasures last a great while yet.

So see and hear yonder the divine Vesuvius, who joins in celebrating the festival in such right good earnest,” cried Dian, who plunged as deeply into the waves of joy as an Ischian. Albano looked over toward the flame, flickering high in the starry heaven, and, like a god, having the great thunder beneath it, and he saw how the night had made the promontory of Misenum loom up like a cloud beside the volcano. Beside them burned thousands of lamps on the royal palace of the neighboring island of Procida.

Procida con l’ Epomeo

While he looked out over the sea, whose coasts were sunk into the night, and which lay stretching away like another night, immeasurable and gloomy, he saw now and then a dissolving splendor sweep over it, which flowed on ever broader and brighter. A distant torch also showed itself in the air, whose flashing drew long, fiery furrows through the glimmering waves. There drew near a bark, with its sail taken in, because the wind blew offshore. Female forms appeared on board, among which, one of royal stature, along whose red silken dress the torch-glare streamed down, held her eyes fixed upon Vesuvius. As they sailed nearer, and the brighter sea blazed up on either side under the dashing oars, it seemed as if a goddess were coming, around whom the sea swims with enraptured flames, and who knows it not.

All stepped out on shore at some distance, where by appointment, as it seemed, servants had been waiting to make everything easy. A smaller person, provided with a double opera glass, took a short farewell of the tall one, and went away with a considerable retinue. The red-dressed one drew a white veil over her face and went, accompanied by two virgins, gravely and like a princess, to the spot where Albano and the music were.

Albano stood near her; two great black eyes, filled with fire and resting upon life with inward earnestness, streamed through the veil, which portrayed the proud, straight forehead and nose. In the whole appearance, there was to him something familiar and yet great; she stood before him as a Fairy Queen, who had long ago with a heavenly countenance bent down over his cradle and looked in with smiles and blessings, and whom the spirit now recognizes again with its old love. He thought perhaps of a name, which spirits had named to him, but that presence seemed here impossible.

She fixed her eye complaisantly on the play of two virgins, who, neatly clad in silk, with gold-edged silken aprons, danced gracefully, with modestly drooping eyelids to the tambourine of a third; the two other virgins,which the stranger had brought with her, and Agata, sang sweetly in Italian half-voice to the graceful joy. “It is all done in fact,” said an old man to the strange lady, “to the honor of the Holy Virgin and St. Nicholas.” She nodded slowly a serious yes.

At this moment there stood, all at once, Luna, played about with the sacrificial fire of Vesuvius, over in the sky, as the proud goddess of the sun-god; not pale, but fiery, as it were, a thunder-goddess over the thunder of the mountain. And Albano cried, involuntarily, “God! the great moon!” The stranger quickly threw back her veil, and looked around significantly after the voice as after a familiar one; when she had looked upon the strange youth for a long time, she turned toward the moon over Vesuvius.

But Albano was agitated by a god, and dazzled by a wonder; he saw here Linda de Romeiro. When she raised the veil, beauty and brightness streamed out of a rising son; delicate, maidenly colors; lovely lines and sweet fullness of youth played like a flower garden about the brow of a goddess, with some blossoms around the holy seriousness and mighty will on brow and lip, and around the dark glow of the large eye. How had the pictures lied about her … how feebly had they expressed this spirit and this life!

As if the hour would fain worthily invest the shining apparition, so beautifully did heaven and earth with all rays of life play into each other. Love-thirsty stars flew like heaven-butterflies into the sea. The moon had soared away over the impetuous earth-flame of Vesuvius, and spread her tender light over the happy world, the sea and the shores. Epomeo hovered with his silvered woods, and with the hermitage of his summit high in the night blue. Near by stirred the life of the singing, dancing ones. with their prayers and their festal rockets which they were sending aloft.

When Linda had long looked across the sea toward Vesuvius, she spoke, of herself, to the silent Albano, by way of answering his exclamation, and making up for her sudden turning round and staring at him. “I come from Vesuvius,” said she; “But he is quite as sublime near at hand as far off, which is so singular.”

Altogether strange and spirit-like did it sound to him, that he really heard this voice. With one that indicated deep emotion, he replied: “In this land, however, everything is great indeed; even the little is made great by the large. This little human pleasure island here between the burnt-out volcano and the burning one … all is at one, and therefore right and so godlike.”

At once attracted and distracted, not knowing him, although previously struck with the resemblance of his voice to Roquairol, yet gladly reflecting on his simple words, she looked longer than she was aware at the ingenuous, but daring and warm eye of the youth. Turning slowly away, she made no reply, and again looked silently at the sports.

Dian, who already for a long time had been looking at the fair stranger, found at last in his memory her name; and came to her with the half-proud, half-embarrassed look of artists toward rank. She did not recognize him. “The Greek, Dian,” said Albano, “noble Countess!”

Surprised at the Count’s recognition of her, she said to him, “I do not know you.”

“You know my father,” said Albano; “the Knight Cesara.”

“O Dio!” cried the Spanish maiden; startled, she became a lily, a rose, a flame…

To be continued