Category Archives: Heine

Heinrich Heine: “The Romantic School … again” Part 3 of 8

Excerpt, “The Prose Writings of Heinrich Heine: Edited, with an Introduction, by Havelock Ellis.” Walter Scott, London: 23 Warwick Lane, Paternoster Row: 1887.

The Romantic School … Part Three

Here the Schlegels reveal the same impotency that we seem to discover in Lessing. The latter also, strong as he is in negation, is equally weak in affirmation; seldom can he lay down any fundamental principle, and even more rarely, a correct one. He lacks the firm foundation of a philosophy, or a synthetic system. In this respect the Schlegels are still more woefully lacking. Many fables are rife concerning the influence of Fichtean idealism and Schelling’s philosophy of nature upon the romantic school, and it is even asserted that the latter is entirely the result of the former.

I can, however, at the most discover the traces of only a few stray thoughts of Fichte and Schelling, but by no means the impress of a system of philosophy. It is true that Schelling, who at that time was delivering lectures at Jena, had personally a great influence upon the romantic school. Schelling is also somewhat of a poet, a fact not generally known in France, and it is said that he is still in doubt whether he shall not publish his entire philosophical works in poetical, yes, even in metrical form. This doubt is characteristic of the man.

But if the Schlegels could give no definite, reliable theory for the masterpieces which they bespoke of the poets of their school, they atoned for these shortcomings by commending as models the best works of art of the past, and by making them accessible to their disciples. These were chiefly the Christian-Catholic productions of the middle ages. The translation of Shakespeare, who stands at the frontier of this art and with Protestant clearness smiles over into our modern era, was solely intended for polemical purposes, the present discussion of which space forbids. It was undertaken by A. W. Schlegel at a time when the enthusiasm for the middle ages had not yet reached its most extravagant height.

Later, when this did occur, Calderon was translated and ranked far above Shakespeare. For the works of Calderon bear most distinctly the impress of the poetry of the middle ages—particularly of the two principal epochs of knight-errantry and monasticism. The pious comedies of the Castilian priest-poet, whose poetical flowers had been besprinkled with holy water and canonical perfumes, with all their pious grandezza, with all their sacerdotal splendour, with all their sanctimonious balderdash, were now set up as models, and Germany swarmed with fantastically-pious, insanely-profound poems, over which it was the fashion to work one’s self into a mystic ecstasy of admiration, as in The Devotion to the Cross, or to fight in honour of the Madonna, as in The Constant Prince. Zacharias Werner carried the nonsense as far as it might be safely done without being imprisoned by the authorities in a lunatic asylum.

Our poetry, said the Schlegels, is superannuated; our muse is an old and wrinkled hag; our Cupid is no fair youth, but a shrunken, grey-haired dwarf. Our emotions are withered; our imagination is dried up: we must re-invigorate ourselves. We must seek again the choked-up springs of the naive, simple poetry of the middle ages, where bubbles the elixir of youth.

When the parched, thirsty multitude heard this, they did not long delay. They were eager to be again young and blooming, and, hastening to those miraculous waters, quaffed and gulped with intemperate greediness. But the same fate befell them as happened to the aged waiting-maid who noticed that her mistress possessed a magic elixir which restored youth. During her lady’s absence she took from the toilet drawer the small flagon which contained the elixir, but, instead of drinking only a few drops, she took a long deep draught, so that through the power of the rejuvenating beverage she became not only young again, but even a puny, puling babe. In sooth, so was it with our excellent Ludwig Tieck, one of the best poets of this school; he drank so deeply of the medieval folk tales and ballads that he became almost as a child again, and dropped into that childlike lisping which it cost Madame de Staël so much painstaking to admire. She confesses that she found it rather strange to have one of the characters in a drama make his debut with a monologue, which begins with the words:—”I am the brave Bonifacius, and I come to tell you,” etc.

By his romance, Sternbald’s Wanderungen, and through his publication of the Herzensergies sungen eines Kunstliebenden Klosterbruders, written by a certain Wackenroder, Ludwig Tieck sought to set up the naive, crude beginnings of art as models. The piety and childishness of these works, which are revealed in their technical awkwardness, were recommended for imitation. Raphael was to be ignored entirely; his teacher, Perugino, fared almost as badly, although rated somewhat higher, for it was claimed that he showed some traces of those beauties which were to be found in their full bloom in the immortal masterpieces of Fra Giovanno Angelico da Fiesole, and were so devoutly admired.

If the reader wishes to form an idea of the taste of the art-enthusiasts of that period, let him go to the Louvre, where the best pictures of those masters, who were then worshipped without bounds, are still on exhibition; and if the reader wishes to form an idea of the great mass of poets who at that time, in all possible varieties of verse, imitated the poetry of the middle ages, let him visit the lunatic asylum at Charenton.

I believe, however, that those pictures in the first salon of the Louvre are still too graceful to give the observer a correct idea of the art ideals of that period. The pictures of the old Italian school must be imagined translated into the old German, for the works of the old German painters were considered more artless and childlike, and therefore more worthy of imitation than the old Italian. It was claimed that we Germans, with our Gemüth, a word for which the French language has no equivalent, have been able to form a more profound conception of Christianity than other nations, and Frederic Schlegel, and his friend, Joseph Görres, rummaged among the ancient Rhine cities for the remains of old German pictures and statuary, which were superstitiously worshipped as holy relics.

I have just likened the German Parnassus of that period to Charenton. Even that, however, is too mild a comparison. A French madness falls far short of a German lunacy in violence, for in the latter, as Polonius would say, there is method. With a pedantry without its equal, with an intense conscientiousness, with a profundity of which a superficial French fool can form no conception, this German folly was pursued.

The political condition of Germany was particularly favourable to those Christian old German tendencies. “Need teaches prayer,” says the proverb; and truly never was the need greater in Germany. Hence the masses were more than ever inclined to prayer, to religion, to Christianity. No people is more loyally attached to its rulers than are the Germans. And more even than the sorrowful condition to which the country was reduced through war and foreign rule did the mournful spectacle of their vanquished princes, creeping at the feet of Napoleon, afflict and grieve the Germans.

The whole nation resembled those faithful old servants in once great but now reduced families, who feel more keenly than even their masters all the humiliations to which the latter are exposed, and who in secret weep most bitterly when the family silver is to be sold, and who clandestinely contribute their pitiful savings, so that patrician wax candles and not plebeian tallow dips shall grace the family table—just as we see it so touchingly depicted in the old plays. The universal sadness found consolation in religion, and there ensued a pious resignation to the will of God, from whom alone help could come.

And, in fact, against Napoleon none could help but God Himself. No reliance could be placed on the earthly legions; hence all eyes were religiously turned to Heaven.

We would have submitted to Napoleon quietly enough, but our princes, while they hoped for deliverance through Heaven, were at the same time not unfriendly to the thought, that the united strength of their subjects might be very useful in effecting their purpose. Hence they sought to awaken in the German people a sense of homogeneity, and even the most exalted personages now spoke of a German nationality, of a common German fatherland, of a union of the Christian-Germanic races, of the unity of Germany. We were commanded to be patriotic, and straightway we became patriots,—for we always obey when our princes command.

But it must not be supposed that the word “patriotism” means the same in Germany as in France. The patriotism of the French consists in this: the heart warms; through this warmth it expands; it enlarges so as to encompass, with its all-embracing love, not only the nearest and dearest, but all France, all civilisation. The patriotism of the Germans, on the contrary, consists in narrowing and contracting the heart, just as leather contracts in the cold; in hating foreigners; in ceasing to be European and cosmopolitan, and in adopting a narrow-minded and exclusive Germanism.

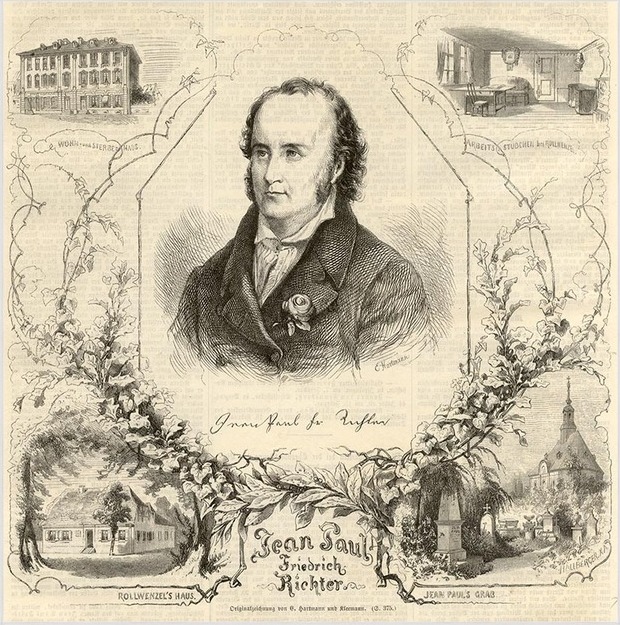

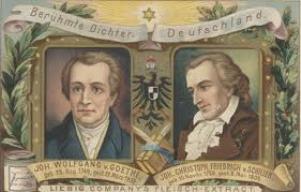

We beheld this ideal empire of churlishness organised into a system by Herr Jahn; with it began the crusade of the vulgar, the coarse, the great unwashed—against the grandest and holiest idea ever brought forth in Germany, the idea of humanitarianism; the idea of the universal brotherhood of mankind, of cosmopolitanism—an idea to which our great minds, Lessing, Herder, Schiller, Goethe, Jean Paul, and all people of culture in Germany, have ever paid homage.

With the events that speedily followed you are only too familiar. After God, the snow, and the Cossacks had destroyed the best portion of Napoleon’s forces, we Germans received the command from those highest in authority to free ourselves from the foreign yoke, and we straightway flamed with manly wrath at the bondage too long endured; and we let ourselves be excited to enthusiasm by the fine melodies, but bad verses, of Körner’s ballads, and we fought until we won our freedom—for we always do what our princes command.

At a period when the crusade against Napoleon was forming, a school which was inimical to everything French, and which exalted everything in art and life that was Teutonic, could not help achieving great popularity. The Romantic School at that time went hand in hand with the machinations of the government and the secret societies, and A. W. Schlegel conspired against Racine with the same aim that Minister Stein plotted against Napoleon. This school of literature floated with the stream of the times; that is to say, with the stream that flowed backwards to its source.

When finally German patriotism and nationality were victorious, the popular Teutonic-Christian-romantic school, “the new-German-religious-patriotic art-school,” triumphed also. Napoleon, the great classic, who was as classic as Alexander or Ceasar, was overthrown, and August William and Frederic Schlegel, the petty romanticists, who were as romantic as Tom Thumb and Puss in Boots, strutted about as victors.

But the reaction which always follows excess was in this case not long in coming. As the spiritualism of Christianity was a reaction against the brutal rule of imperial Roman materialism; as the revival of the love for Grecian art and science was a reaction against the extravagances of Christian spiritualism; as the romanticism of the middle ages may also be considered as a reaction against the vapid apings of antique classic art; so also do we now behold a reaction against the re-introduction of that catholic, feudal mode of thought, of that knight-errantry and priestdom, which were being inculcated through literature and the pictorial arts, under bewildering circumstances.

For when the artists of the middle ages were recommended as models, and were so highly praised and admired, the only explanation of their superiority that could be given was that these men believed in that which they depicted, and that, therefore, with their artless conceptions they could accomplish more than the later sceptical artists, notwithstanding that the latter excelled in technical skill. In short, it was claimed that faith worked wonders, and, in truth, how else could the transcendent merits of a Fra Angelico da Fiesole or the poems of Brother Ottfried be explained? Hence the artists who were honest in their devotion to art, and who sought to imitate the pious distortions of those miraculous pictures, the sacred uncouthness of those marvel-abounding poems, and the inexplicable mysticisms of those olden works—these artists determined to wander to the same hippocrene whence the old masters had derived their supernatural inspiration.

They made a pilgrimage to Rome, where the vicegerent of Christ was to re-invigorate consumptive German art with asses’ milk. In brief, they betook themselves to the lap of the Roman-Catholic-Apostolic Church, where alone, according to their doctrine, salvation was to be secured. Many of the adherents of the romantic school—for instance, Joseph Görres and Clemens Brentano—were Catholics by birth, and required no formal ceremony to mark their re-adhesion to the Catholic faith; they merely renounced their former free-thinking views. Others, however, such as Frederic Schlegel, Ludwig Tieck, Novalis, Werner, Schütz, Carove, Adam Müller, etc., were born and bred Protestants, and their conversion to Catholicism required a public ceremony. The above list of names includes only authors; the number of painters, who in swarms simultaneously abjured Protestantism and reason, was much larger.

When it was seen how these young people made obeisance, as it were, to the Roman Catholic Church, and pressed their way into ancient prisons of the mind, from which their fathers had so valiantly liberated themselves, much misgiving was felt in Germany. But when it was discovered that this propaganda was the work of priests and aristocrats, who had conspired against the religious and political liberties of Europe; when it was seen that it was Jesuitism itself which was seeking, with the dulcet tones of Romanticism, to lure the youth of Germany to their ruin, after the manner of the mythical rat-catcher of Hamelin; when all this became known, there was great excitement and indignation in Germany among the friends of Protestantism and intellectual freedom.

I have mentioned intellectual freedom and Protestantism together; although, in Germany, I profess the Protestant religion, yet I trust no one will accuse me of a prejudice in its favour. It is entirely without partiality that I have named Protestantism and free-thought together, for in Germany they really stand on a friendly footing towards one another. At all events they are akin, and that as mother and daughter.

Even if the Protestant Church may be charged with a certain odious narrow-mindedness, yet to its immortal honour be it said, that by allowing the right of free investigation in the Christian religion, and by liberating the minds of men from the yoke of authority, it made it possible for free-thought to strike root in Germany, and for science to develop an independent existence. Although German philosophy now proudly takes its stand by the side of the Protestant Church; yes, even assumes an air of superiority; yet it is only the daughter of the latter, and as such owes her filial respect and consideration; and when threatened by Jesuitism, the common foe of them both, the bonds of kindred demanded that they should combine for mutual defence.

All the friends of intellectual freedom and the Protestant Church, sceptics as well as orthodox, simultaneously arose against the restoration of Catholicism, and, as a matter of course, the Liberals, who were not specially concerned either for the welfare of the Protestant Church or of philosophy, but for the interests of civil liberty, also joined the ranks of this opposition. In Germany, however, the Liberals had always, up to the present time, been students both of philosophy and theology, and the idea of liberty for which they fought was always the same, whether the subject under discussion was exclusively political, philosophical, or theological. This is most clearly manifest in the life of the man, who, at the very outset of the romantic school in Germany, undermined its foundation, and contributed the most to its overthrow. I refer to Johann Heinrich Voss.

To be continued…

Link to Part Four

Heinrich Heine: “The Romantic School… again” Part 2 of 8

Excerpt, “The Prose Writings of Heinrich Heine: Edited, with an Introduction, by Havelock Ellis.” Walter Scott, London: 23 Warwick Lane, Paternoster Row: 1887.

The Romantic School — Part Two

But human genius can transfigure deformity itself, and many painters succeeded in accomplishing the unnatural task beautifully and sublimely. The Italians, in particular, glorified beauty,—it is true, somewhat at the expense of spirituality,—and raised themselves aloft to an ideality which reached its perfection in the many representations of the Madonna. Where it concerned the Madonna, the Catholic clergy always made some concessions to sensuality. This image of an immaculate beauty, transfigured by motherly love and sorrow, was privileged to receive the homage of poet and painter, and to be decked with all the charms that could allure the senses.

For this image was a magnet, which was to draw the great masses into the pale of Christianity. Madonna Maria was the pretty dame du comptoir of the Catholic Church, whose customers, especially the barbarians of the North, she attracted and held fast by her celestial smiles.

During the middle ages architecture was of the same character as the other arts; for, indeed, at that period all manifestations of life harmonised most wonderfully. In architecture, as in poetry, this parabolising tendency was evident. Now, when we enter an old cathedral, we have scarcely a hint of the esoteric meaning of its stony symbolism. Only the general impression forces itself on our mind. We feel the exaltation of the spirit and the abasement of the flesh.

The interior of the cathedral is a hollow cross, and we walk here amid the instruments of martyrdom itself. The variegated windows cast on us their red and green lights, like drops of blood and ichor; requiems for the dead resound through the aisles; under our feet are gravestones and decay; in harmony with the colossal pillars, the soul soars aloft, painfully tearing itself away from the body, which sinks to the ground like a cast-off garment. When one views from without these Gothic cathedrals, these immense structures, that are built so airily, so delicately, so daintily, as transparent as if carved, like Brabant laces made of marble, then only does one realise the might of that art which could achieve a mastery over stone, so that even this stubborn substance should appear spectrally etherealised, and be an exponent of Christian spiritualism.

But the arts are only the mirror of life; and when Catholicism disappeared from daily life, so also it faded and vanished out of the arts. At the time of the Reformation Catholic poetry was gradually dying out in Europe, and in its place we behold the long-buried Grecian style of poetry again reviving. It was, in sooth, only an artificial spring, the work of the gardener and not of the sun; the trees and flowers were stuck in narrow pots, and a glass sky protected them from the wind and cold weather.

In the world’s history every event is not the direct consequence of another, but all events mutually act and react on one another. It was not alone through the Greek scholars who, after the conquest of Constantinople, immigrated over to us, that the love for Grecian art, and the striving to imitate it, became universal among us; but in art as in life, there was stirring a contemporary Protestantism. Leo X., the magnificent Medici, was just as zealous a Protestant as Luther; and as in Wittenburg protest was offered in Latin prose, so in Rome the protest was made in stone, colours, and ottava rime.

For do not the vigorous marble statues of Michael Angelo, Giulio Romano’s laughing nymph-faces, and the life-intoxicated merriment in the verses of Master Ludovico, offer a protesting contrast to the old, gloomy, withered Catholicism? The painters of Italy combated priestdom more effectively, perhaps, than did the Saxon theologians. The glowing flesh in the paintings of Titian,—all that is simple Protestantism. The limbs of his Venus are much more fundamental theses than those which the German monk nailed to the church door of Wittenburg.

Mankind felt itself suddenly liberated, as it were, from the thraldom of a thousand years; the artists, in particular, breathed freely again when the Alp-like burden of Christianity was rolled from off their breasts; they plunged enthusiastically into the sea of Grecian mirthfulness, from whose foam the goddess of beauty again rose to meet them; again did the painters depict the ambrosial joys of Olympus; again did the sculptors, with the olden love, chisel the heroes of antiquity from out the marble blocks; again did the poets sing of the house of Atreus and of Laios; a new era of classic poetry arose.

In France, under Louis XIV., this neo-classic poetry exhibited a polished perfection, and, to a certain extent, even originality. Through the political influence of the grand monarque this new classic poetry spread over the rest of Europe. In Italy, where it was already at home, it received a French colouring; the Anjous brought with them to Spain the heroes of French tragedy; it accompanied Madame Henriette to England; and, as a matter of course, we Germans modelled our clumsy temple of art after the bepowdered Olympus of Versailles. The most famous high priest of this temple was Gottsched, that old periwigged pate, whom our dear Goethe has so felicitously described in his memoirs.

Lessing was the literary Arminius who emancipated our theatre from that foreign rule. He showed us the vapidness, the ridiculousness, the tastelessness, of those apings of the French stage, which itself was but an imitation of the Greek. But not only by his criticism, but also through his own works of art, did he become the founder of modern German original literature. All the paths of the intellect, all the phases of life, did this man pursue with disinterested enthusiasm. Art, theology, antiquarianism, poetry, dramatic criticism, history,—he studied these all with the same zeal and with the same aim. In all his works breathes the same grand social idea, the same progressive humanity, the same religion of reason, whose John he was, and whose Messiah we still await. This religion he preached always, but alas! often quite alone and in the desert. Moreover, he lacked the skill to transmute stones into bread.

The greater portion of his life was spent in poverty and misery—a curse which rests on almost all the great minds of Germany, and which probably will only be overcome by the political emancipation. Lessing was more deeply interested in political questions than was imagined,—a characteristic which we entirely miss in his contemporaries. Only now do we comprehend what he had in view by his description of the petty despotisms in Emilia Galotti. At that time he was considered merely a champion of intellectual liberty and an opponent of clerical intolerance; his theological writings were better understood. The fragments “Concerning the Education of the Human race,” which have been translated into French by Eugene Rodrigue, will perhaps suffice to give the French an idea of the wide scope of Lessing’s genius. His two critical works which have had the most influence on art are his Hamburger Dramaturgie and his Laocoon, or Concerning the Limits of Painting and Poetry. His best dramatic works are Emilia Galotti, Minna von Barnhelm, and Nathan the Wise.

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing was born January 22nd, 1729, at Kamenz, in Upper Lusatia, and died February 15th, 1781, at Brunswick. He was a whole man, who; while with his polemics waging destructive battle against the old, at the same time created something newer and better. “He resembled,” says a German author, “those pious Jews, who, at the second building of the temple, were often disturbed by the attacks of their enemies, and with one hand would fight against the foe, while with the other hand they continued to work at the house of God.” This is not the place to discuss Lessing more fully, but I cannot refrain from saying that, in the whole range of literary history, he is the author whom I most love.

I desire here to call attention to another author, who worked in the same spirit and with the same aim, and who may be regarded as Lessing’s most legitimate successor. It is true, a criticism of this author would be out of place here, for he occupies a peculiarly isolated place in the history of literature, and his relation to his epoch and contemporaries cannot even now be definitely pronounced. I refer to Johann Gottfried Herder, born in 1744, at Morungen, in East Prussia; died in 1803, at Weimar, in Saxony.

The history of literature is a great morgue, wherein each seeks the dead who are near or dear to him. And when, among the corpses of so many petty men, I behold the noble features of a Lessing or a Herder, my heart throbs with emotion. How could I pass you without pressing a hasty kiss on your pale lips?

But if Lessing effectually put an end to the servile apings of Franco-Grecian art, yet, by directing attention to the true art-works of Grecian antiquity, to a certain extent he gave an impetus to a new and equally silly species of imitation. Through his warfare against religious superstition he even advanced a certain narrow-minded jejune enlightenment, which at that time vaunted itself in Berlin; the sainted Nicolai was its principal mouthpiece, and the German Encyclopedia its arsenal. The most wretched mediocrity began again to raise its head, more disgustingly than ever. Imbecility, vapidity, and the commonplace distended themselves like the frog in the fable.

It is an error to believe that Goethe, who at that time had already appeared upon the scene, had met with general recognition. His Goetz von Berlichingen and his Werther were received with enthusiasm, but the works of the most ordinary bungler not less so, and Goethe occupied but a small niche in the temple of literature. It is true, as said before, that the public welcomed Goetz and Werther with delight, but more on account of the subject matter than their artistic merits, which few were able to appreciate. Of these masterpieces, Goetz von Berlichingen was a dramatised romance of chivalry, which was the popular style at that time. In Werther the public saw only an embellished account of an episode in real life—namely, the story of young Jerusalem, a youth who shot himself from disappointed love, thereby creating quite a commotion in that dead-calm period.

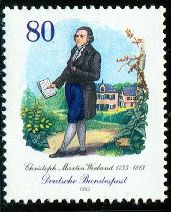

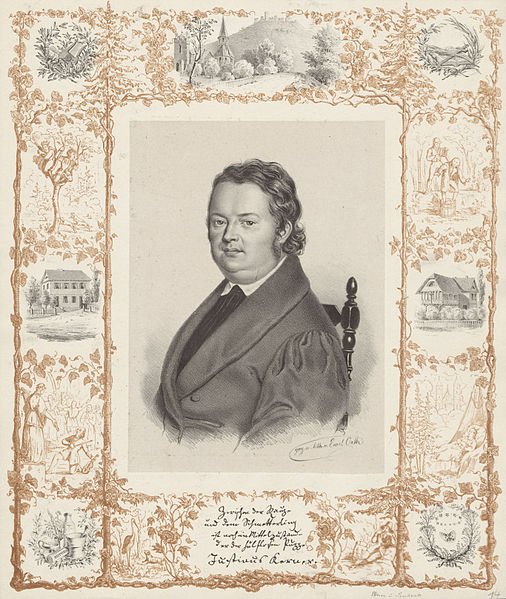

Tears were shed over his pathetic letters, and it was shrewdly observed that the manner in which Werther had been ostracised from the society of the nobility must have increased his weariness of life. The discussion concerning suicide brought the book still more into notice; a few fools hit upon the idea of shooting themselves in imitation of Werther, and thus the book made a marked sensation. But the romances of August Lafontaine were in equal demand, and as the latter was a voluminous writer, it followed that he was more famous than Wolfgang Goethe. Wieland was the great poet of that period, and his only rival was Herr Ramler of Berlin. Wieland was worshipped idolatrously, more than Goethe ever was. Iffland, with his lachrymose domestic dramas, and Kotzebue’s farces, with their stale witticisms, ruled the stage.

It was against this literature that, in the closing years of the last century, there arose in Germany a new school, which we have designated the Romantic School. At the head of this school stand the brothers August William and Frederic Schlegel. Jena, where these two brothers, together with many kindred spirits, were wont to come and go, was the central point from which the new aesthetic dogma radiated. I advisedly say dogma, for this school began with a criticism of the art productions of the past, and with recipes for the art works of the future. In both of these fields the Schlegelian school has rendered good service to aesthetic criticism. In criticising the art works of the past, either their defects and imperfections were set forth, or their merits and beauties illustrated. In their polemics, in their exposure of artistic shortcomings and imperfections, the Schlegels were entirely imitators of Lessing; they seized upon his great battle-sword, but the arm of August William Schlegel was far too feeble, and the sight of his brother Frederic too much obscured by mystic clouds; the former could not strike so strong, nor the latter so sure and telling a blow as Lessing. In reproductive criticism, however, where the beauties of a work of art were to be brought out clearly; where a delicate perception of individualities was required; and where these were to be made intelligible, the Schlegels are far superior to Lessing. But what shall I say concerning their recipes for producing masterpieces?

To be continued…

Heinrich Heine: “The Romantic School…again” Part I of 9

Excerpt, “The Prose Writings of Heinrich Heine: Edited, with an Introduction, by Havelock Ellis.” Walter Scott, London: 23 Warwick Lane, Paternoster Row: 1887.

THE ROMANTIC SCHOOL

[The Romantic School, one of Heine’s chief works, of which the most interesting portions are here given, was published in 1833. It was first written in French, as a counterblast to Madame de Staël’s De l’Allemagne, forming a series of articles in the Europe Litteraire. Notwithstanding many errors of detail, and some occasional injustice, it remains by far the best account of the most important aspect of German literature. Indirectly Heine wished to lay down the programme of the future, for he regarded himself as the last of the Romantic poets, and the inaugurator of a new school. The following translation is Mr. Fleishman’s; it has been carefully revised.]

MADAME de Staël’s work, De l’Allemagne, is the only comprehensive account of the intellectual life of Germany which has been accessible to the French; and yet since her book appeared a considerable period has elapsed, and an entirely new school of literature has arisen in Germany. Is it only a transitional literature? Has it already reached its zenith? Has it already begun to decline? Opinions are divided concerning it.

The majority believe that with the death of Goethe a new literary era begins in Germany; that with him the old Germany also descended to its grave; that the aristocratic period of literature was ended, and the democratic just beginning; or, as a French journal recently phrased it, “The intellectual dominion of the individual has ceased,—the intellectual rule of the many has commenced.”

So far as I am concerned, I do not venture to pass so decided an opinion as to the future evolutions of German intellect. I had already prophesied many years in advance the end of the Goethean art-period, by which name I was the first to designate that era. I could safely venture the prophecy, for I knew very well the ways and the means of those malcontents who sought to overthrow the Goethean art-empire, and it is even claimed that I took part in those seditious outbreaks against Goethe. Now that Goethe is dead, the thought of it fills me with an overpowering sorrow.

While I announce this book as a sequel to Madame de Staël’s De l’Allemagne, and extol her work very highly as being replete with information, I must yet recommend a certain caution in the acceptance of the views enunciated in that book, which I am compelled to characterise as a coterie-book. Madame de Staël’s , of glorious memory, here opened, in the form of a book, a salon in which she received German authors and gave them an opportunity to make themselves known to the civilised world of France. But above the din of the most diverse voices, confusedly discoursing therein, the most audible is the delicate treble of Herr A. W. Schlegel.

Where the large-hearted woman is wholly herself,—where she is uninfluenced by others, and expresses the thoughts of her own radiant soul, displaying all her intellectual fireworks and brilliant follies,—there the book is good, even excellent. But as soon as she yields to foreign influences, as soon as she begins to glorify a school whose spirit is wholly unfamiliar and incomprehensible to her, as soon as through the commendation of this school she furthers certain Ultramontane tendencies which are in direct opposition to her own Protestant clearness, just so soon her book becomes wretched and unenjoyable.

To this unconscious partisanship she adds the evident purpose, through praise of the intellectual activity, the idealism, of Germany, to rebuke the realism then existing among the French, and the materialistic splendours of the Empire. Her book De l’Allemagne resembles in this respect the Germania of Tacitus, who perhaps likewise designed his eulogy of the Germans as an indirect satire against his countrymen. In referring to the school which Madame de Staël’s glorified, and whose tendencies she furthered, I mean the Romantic School. That this was in Germany something quite different from that which was designated by the same name in France, that its tendencies were totally diverse from those of the French Romanticists, will be made clear in the following pages.

But what was the Romantic School in Germany?

It was nothing else than the reawakening of the poetry of the middle ages as it manifested itself in the poems, paintings, and sculptures, in the art and life of those times. This poetry, however, had been developed out of Christianity; it was a passion-flower which had blossomed from the blood of Christ. I know not if the melancholy flower which in Germany we call the passion-flower is known by the same name in France, and if the popular tradition has ascribed to it the same mystical origin.

It is that motley-hued, melancholic flower in whose calyx one may behold a counterfeit presentment of the tools used at the crucifixion of Christ—namely, hammer, pincers, and nails. This flower is by no means unsightly, but only spectral: its aspect fills our souls with a dread pleasure, like those convulsive, sweet emotions that arise from grief. In this respect the passion-flower would be the fittest symbol of Christianity itself, whose most awe-inspiring charm consists in the voluptuousness of pain.

Although in France Christianity and Roman Catholicism are synonymous terms, yet I desire to emphasise the fact, that I here refer to the latter only. I refer to that religion whose earliest dogmas contained a condemnation of all flesh, and not only admitted the supremacy of the spirit over the flesh, but sought to mortify the latter in order thereby to glorify the former.

I refer to that religion through whose unnatural mission vice and hypocrisy came into the world, for through the odium which it cast on the flesh the most innocent gratification of the senses were accounted sins; and, as it was impossible to be entirely spiritual, the growth of hypocrisy was inevitable. I refer to that religion which, by teaching the renunciation of all earthly pleasures, and by inculcating abject humility and angelic patience, became the most efficacious support of despotism.

Men now recognise the nature of that religion, and will no longer be put off with promises of a Heaven hereafter; they know that the material world has also its good, and is not wholly given over to Satan, and now they vindicate the pleasures of the world, this beautiful garden of the gods, our inalienable heritage. Just because we now comprehend so fully all the consequences of that absolute spirituality, we are warranted in believing that the Christian-Catholic theories of the universe are at an end; for every epoch is a sphinx which plunges into the abyss as soon as its problem is solved.

We by no means deny the benefits which the Christian-Catholic theories effected in Europe. They were needed as a wholesome reaction against the terrible colossal materialism which was developed in the Roman Empire, and threatened the annihilation of all the intellectual grandeur of mankind. Just as the licentious memoirs of the last century form the pieces justificatives of the French Revolution; just as the reign of terror seems a necessary medicine when one is familiar with the confessions of the French nobility since the regency; so the wholesomeness of ascetic spirituality becomes manifest when we read Petronius or Apuleius, books

The flesh had become so insolent in this Roman world that Christian discipline was needed to chasten it. After the banquet of a Trimalkion, a hunger-cure, such as Christianity, was required.

Or did, perhaps, the hoary sensualists seek by scourgings to stimulate the cloyed flesh to renewed capacity for enjoyment? Did aging Rome submit to monkish flagellations in order to discover exquisite pleasure in torture itself, voluptuous bliss in pain?

Unfortunate excess! it robbed the Roman body-politic of its last energies. Rome was not destroyed by the division into two empires. On the Bosphorus as on the Tiber, Rome was eaten up by the same Judaic spiritualism, and in both Roman history became the record of a slow dying-away, a death agony that lasted for centuries. Did perhaps murdered Judea, by bequeathing its spiritualism to the Romans, seek to avenge itself on the victorious foe, as did the dying centaur, who so cunningly wheedled the son of Jupiter into wearing the deadly vestment poisoned with his own blood?

In truth, Rome, the Hercules among nations, was so effectually consumed by the Judaic poison that helm and armour fell from its decaying limbs, and its imperious battle tones degenerated into the prayers of snivelling priests and the trilling of eunuchs.

But that which enfeebles the aged strengthens the young. That spiritualism had a wholesome effect on the over-robust races of the north; the ruddy barbarians became spiritualised through Christianity; European civilisation began. This is a praiseworthy and sacred phase of Christianity. The Catholic Church earned in this regard the highest title to our respect and admiration. Through grand, genial institutions it controlled the bestiality of the barbarian hordes of the North, and tamed their brutal materialism.

The works of art in the middle ages give evidence of this mastery of matter by the spirit; and that is often their whole purpose. The epic poems of that time may be easily classified according to the degree in which they show that mastery. Of lyric and dramatic poems nothing is here to be said; for the latter do not exist, and the former are comparatively as much alike in all ages as are the songs of the nightingales in each succeeding spring.

Although the epic poetry of the middle ages was divided into sacred and secular, yet both classes were purely Christian in their nature; for if the sacred poetry related exclusively to the Jewish people and its history, which alone was considered sacred; if its themes were the heroes of the Old and the New Testaments, and their legends—in brief, the Church—still all the Christian views and aims of that period were mirrored in the secular poetry. The flower of the German sacred poetry of the middle ages is, perhaps, Barlaam and Josaphat, a poem in which the dogma of self-denial, of continence, of renunciation, of the scorn of all worldly pleasures, is most consistently expressed.

Next in order of merit I would rank Lobgesang auf den Heiligen Anno, but the latter poem already evinces a marked tendency towards secular themes. It differs in general from the former somewhat as a Byzantine image of a saint differs from an old German representation. Just as in these Byzantine pictures, so also do we find in Barlaam and Josaphat the greatest simplicity; there is no perspective, and the long, lean, statue-like forms, and the grave, ideal countenances, stand severely outlined, as though in bold relief against a background of pale gold.

In the Lobgesang auf den Heiligen Anno, as in the old German pictures, the accessories seem almost more prominent than the subject; and, notwithstanding the bold outlines, every detail is most minutely executed, and one knows not which to admire most, the giant-like conception or the dwarf-like patience of execution. Ottfried’s Evangeliengedicht, which is generally praised as the masterpiece of this sacred poetry, is far inferior to both of these poems.

In the secular poetry we find, as intimated above, first, the cycle of legends called the Nibelungenlied, and the Book of Heroes. In these poems all the ante-Christian modes of thought and feelings are dominant; brute force is not yet moderated into chivalry; the sturdy warriors of the North stand like statues of stone, and the soft light and moral atmosphere of Christianity have not yet penetrated their iron armour.

But dawn is gradually breaking over the old German forests, the ancient Druid oaks are being felled, and in the open arena Christianity and Paganism are battling: all this is portrayed in the cycle of traditions of Charlemagne; even the Crusades with their religious tendencies are mirrored therein. But now from this Christianised, spiritualised brute force is developed the peculiar feature of the middle ages, chivalry, which finally becomes exalted into a religious knighthood.

The earlier knighthood is most felicitously portrayed in the legends of King Arthur, which are full of the most charming gallantry, the most finished courtesy, and the most daring bravery. From the midst of the pleasing, though bizarre, arabesques, and the fantastic, flowery mazes of these tales, we are greeted by the gentle Gawain, the worthy Lancelot of the Lake, by the valiant, gallant, and honest, but somewhat tedious, Wigalois. By the side of this cycle of legends we find the kindred and connected legends of the Holy Grail, in which the religious knighthood is glorified, and in which are to be found the three grandest poems of the middle ages, Titurel, Parcival, and Lohengrin.

In these poems we stand face to face, as it were, with the muse of romantic poetry; we look deep into her large, sad eyes, and ere we are aware she has ensnared us in her network of scholasticism, and drawn us down into the weird depths of medieval mysticism. But further on in this period we find poems which do not unconditionally bow down to Christian spirituality; poems in which it is even attacked, and in which the poet, breaking loose from the fetters of an abstract Christian morality, complacently plunges into the delightful realm of glorious sensuousness.

Nor is it an inferior poet who has left us Tristan and Isolde, the masterpiece of this class. Verily, I must confess that Gottfried von Strasburg, the author of this, the most exquisite poem of the middle ages, is perhaps also the loftiest poet of that period. He surpasses even the grandeur of Wolfram von Eschilbach, whose Parcival, and fragments of Titurel, are so much admired. At present, it is perhaps permissible to praise Meister Gottfried without stint, but in his own time his book and similar poems, to which even Lancelot belonged, were considered Godless and dangerous. Francesca da Polenta and her handsome friend paid dearly for reading together such a book;—the greater danger, it is true, lay in the fact that they suddenly stopped reading.

All the poetry of the middle ages has a certain definite character, through which it differs from the poetry of the Greeks and Romans. In reference to this difference the former is called Romantic, the latter Classic. These names, however, are misleading, and have hitherto caused the most vexatious confusion, which is even increased when we call the antique poetry plastic as well as classic.

In this, particularly, lay the germ of misunderstandings; for artists ought always to treat their subject-matter plastically. Whether it be Christian or pagan, the subject ought to be portrayed in clear contours. In short, plastic configuration should be the main requisite in the modern romantic as well as in antique art. And, in fact, are not the figures in Dante’s Divine Comedy or in the paintings of Raphael just as plastic as those in Virgil or on the walls of Herculaneum?

The difference consists in this,—that the plastic figures in antique art are identical with the thing represented, with the idea which the artist seeks to communicate. Thus, for example, the wanderings of the Odyssey mean nothing else than the wanderings of the man who was a son of Laertes and the husband of Penelope, and was called Ulysses. Thus, again, the Bacchus which is to be seen in the Louvre is nothing more than the charming son of Semele, with a daring melancholy look in his eyes, and an inspired voluptuousness on the soft arched lips. It is otherwise in romantic art: here the wanderings of a knight have an esoteric signification; they typify, perhaps, the mazes of life in general.

The dragon that is vanquished is sin; the almond-tree, that from afar so encouragingly wafts its fragrance to the hero, is the Trinity, the God-Father, God-Son, and God-Holy-Ghost, who together constitute one, just as shell, fibre, and kernel together constitute the almond. When Homer describes the armour of a hero, it is naught else than a good armour, which is worth so many oxen; but when a monk of the middle ages describes in his poem the garments of the Mother of God, you may depend upon it, that by each fold of those garments he typifies some special virtue, and that a peculiar meaning lies hidden in the sacred robes of the immaculate Virgin Mary; as her Son is the kernel of the almond, she is quite appropriately described in the poem as an almond-blossom. Such is the character of that poesy of the middle ages which we designate romantic.

Classic art had to portray only the finite, and its forms could be identical with the artist’s idea. Romantic art had to represent, or rather to typify, the infinite and the spiritual, and therefore was compelled to have recourse to a system of traditional, or rather parabolic, symbols, just as Christ himself had endeavoured to explain and make clear his spiritual meaning through beautiful parables. Hence the mystic, enigmatical, miraculous, and transcendental character of the art-productions of the middle ages. Fancy strives frantically to portray through concrete images that which is purely spiritual, and in the vain endeavour invents the most colossal absurdities; it piles Ossa on Pelion, Parcival on Titurel, to reach heaven.

Similar monstrous abortions of imagination have been produced by the Scandinavians, the Hindoos, and the other races which likewise strive through poetry to represent the infinite; among them also do we find poems which may be regarded as romantic.

Concerning the music of the middle ages little can be said. All records are wanting. It was not until late in the sixteenth century that the masterpieces of Catholic Church music came into existence, and, of their kind, they cannot be too highly prized, for they are the purest expression of Christian spirituality. The recitative arts, being spiritual in their nature, quite appropriately flourished in Christendom. But this religion was less propitious for the plastic arts, for as the latter were to represent the victory of spirit over matter, and were nevertheless compelled to use matter as a means to carry out this representation, they had to accomplish an unnatural task.

Hence sculpture and painting abounded with such revolting subjects as martyrdoms, crucifixions, dying saints, and physical sufferings in general. The treatment of such subjects must have been torture for the artists themselves; and when I look at those distorted images, with pious heads awry, long, thin arms, meagre legs, and graceless drapery, which are intended to represent Christian abstinence and ethereality, I am filled with an unspeakable compassion for the artists of that period. It is true the painters were somewhat more favoured, for colour, the material of their representation, in its intangibility, in its varied lights and shades, was not so completely at variance with spirituality as the material of the sculptors;

But even they, the painters, were compelled to disfigure the patient canvas with the most revolting representations of physical suffering. In truth, when we view certain picture galleries, and behold nothing but scenes of blood, scourgings, and executions, we are fain to believe that the old masters painted these pictures for the gallery of an executioner.

To be continued…

Link to Part Four

Heinrich Heine: “A Princess Came in Dreams to Me”

Excerpt, “Lyrics and Ballads of Heine and Other German Poets.” Translated by Frances Hellman. 1892.

Heinrich Heine: “Upon the Far Horizon”

Excerpt, “Lyrics and Ballads of Heine and Other German Poets.” Translated by Frances Hellman. 1892.

Heinrich Heine: “What I Have, Ask Not, My Darling”

Excerpt, “Lyrics and Ballads of Heine and Other German Poets.” Translated by Frances Hellman. 1892.

Heinrich Heine: “To My Mother”

Excerpt, “The Sonnets of Europe.” A Volume of Translations, selected and arranged, with notes, by Samuel Waddington. 1886.

.

Heinrich Heine: “The Two Grenadiers” 1822

THE TWO GRENADIERS

To France were traveling two grenadiers,

From prison in Russia returning,

And when they came to the German frontiers,

They hung down their heads in mourning.

There came the heart-breaking news to their ears

That France was by fortune forsaken;

Scattered and slain were her brave grenadiers,

And Napoleon, Napoleon was taken.

Then wept together those two grenadiers

O'er their country's departed glory;

"Woe's me," cried one, in the midst of his tears,

"My old wound--how it burns at the story!"

The other said: "The end has come,

What avails any longer living

Yet have I a wife and child at home,

For an absent father grieving.

"Who cares for wife? Who cares for child?

Dearer thoughts in my bosom awaken;

Go beg, wife and child, when with hunger wild,

For Napoleon, Napoleon is taken!

"Oh, grant me, brother, my only prayer,

When death my eyes is closing:

Take me to France, and bury me there;

In France be my ashes reposing.

"This cross of the Legion of Honor bright,

Let it lie near my heart, upon me;

Give me my musket in my hand,

And gird my sabre on me.

"So will I lie, and arise no more,

My watch like a sentinel keeping,

Till I hear the cannon's thundering roar,

And the squadrons above me sweeping.

"Then the Emperor comes! and his banners wave,

With their eagles o'er him bending,

And I will come forth, all in arms, from my grave,

Napoleon, Napoleon attending!"

.

Heinrich Heine: Cholera in Paris 3

Excerpt from The Works of Heinrich Heine, Vol. 14. Translated from the German by Charles Godfrey Leland.

Since these events all has been quiet again, or, as Horatius Sebastiani would say, “L’ordre regne a Paris.” There is a stony stillness as of death in every face. For many evenings very few people were seen on the Boulevards, and they hurried along with hands or handkerchiefs held over their faces. The theatres are as if perished and passed away. When I enter a salon, people are amazed to see me still in Paris, since I am not detained by urgent business. In fact, most strangers, and especially my fellow-countrymen, left long since.

Since these events all has been quiet again, or, as Horatius Sebastiani would say, “L’ordre regne a Paris.” There is a stony stillness as of death in every face. For many evenings very few people were seen on the Boulevards, and they hurried along with hands or handkerchiefs held over their faces. The theatres are as if perished and passed away. When I enter a salon, people are amazed to see me still in Paris, since I am not detained by urgent business. In fact, most strangers, and especially my fellow-countrymen, left long since.

Obedient parents received from their children orders to return at once. God-fearing sons fulfilled without delay and tender wishes of their loving sires, who longed to see them in their homes again. Honour thy father and thy mother … then, thy days shall be prolonged upon the earth! In others, too, there suddenly awoke an endless yearning for their fatherland, for the romantic valleys of the noble Rhine, for the dear mountains, for winsome Suabia, the land of pure true love and woman’s faith, of joyous ballads and of healthy air. It is said that thus far more than 120,000 passports have been issued at the Hotel de Ville.

Although the cholera evidently first attacked the poorer classes; the rich still very promptly took to flight. Certain parvenus should not be too severely judged for having done so, for they probably reflected that the cholera, which came hither all the way from Asia, does not know that we have quite lately grown rich on Change, and thinking that we are still poor devils, will send us to turn up our toes to the daisies. M. Aguado, one of the richest bankers and a chevalier of the Legion of Honour, was field-marshal in this great retreat. The knight is said to have glared with mad apprehension out of the coach-window, and believed that his footman all in blue who stood behind was blue Death himself or the cholera morbus.

The multiple murmured bitterly when it saw how the rich fled away, and, well packed with doctors and drugs, took refuge in healthier climes. The poor man saw with bitter discontent that money had become a protection also against death. The greater portion of the juste milieu and of la haute finance have also departed, and now live in their chateaux. But the real representatives of wealth, the Messieurs Rothschild, have, however, quietly remained in Paris, thereby manifesting that they are great-minded and brave. Casimir Perier also showed himself great and brave in visiting the Hotel Dieu or hospital after the cholera had broken out.

It should have grieved even his enemies that he was attacked by the cholera after this visit. He did not, however, succumb to it, being in himself a much worse pestilence. The young Prince d’Orleans, who in company with Perier, visited the hospital, also deserves the most honourable mention. But the whole royal family has behaved quite as nobly in this sad time. When the cholera broke out, the Queen assembled her friends and servants, and distributed among them flannel bandages, which were mostly made by her own hands.

The manners and customs of ancient chivalry are not yet extinct; they have only changed into domestic citizen-like forms; great ladies now bedeck their champions with less poetical, but more practical and healthier scarfs. We live no longer in the ancient days of helm and harness and of warring knights, but in the peaceful, honest bourgeois days of under-jackets and warm bandages; that is, no longer in the iron age, but that of flannel – flannel everywhere. It is , in fact, the best cuirass against the cholera, our most cruel enemy. Venus, according to the Figaro, would wear today a girdle of flannel. I myself am up to my neck in flannel, and consider myself cholera-proof. The King himself wears now a belt of the best bourgeois flannel.

Nor should I forget to mention that he, the citizen king, during the general suffering, gave a great deal of money to the poor citizens, and showed himself inspired with civic sympathy and noble. And while in the vein, I will also praise the Archbishop of Paris, who also went to the Hotel Dieu, , after the Prince Royal and Perier had made their visits, to console the patients. He had long prophesied that God would send the cholera as a judgment and punishment on the people “for having banished a most Christian king, and struck out the privileges of the Catholic religion for the Charte.”

Now when the wrath of God falls on the sinners, M. de Quelen would fain send prayers to heaven and implore grace, at least for the innocent, for it appears that many Carlists also die. Moreover, M. de Quelen offered his Chateau de Conflans to be used as a hospital. The proffer was declined by the Government because the building is in such a ruined and deplorable condition that it would cost too much to repair it. And the Bishop had, as a condition, exacted that he should have unconditional authority or carte blanche in directing the hospital.

But it was deemed too dangerous an experiment to entrust the souls of the poor patients, whose bodies were already suffering terribly, to the tortures of attempted salvation, which the Archbishop and his familiars intended to inflict. It was thought better to let the hardened Revolutionary sinners die simply of the cholera, without threats of eternal damnation and hell-fire, without confession or extreme unction. For though it is declared that the Catholic is a religion perfectly adapted to the unhappy time through which we are now passing, the French will have none of it for fear lest they should be obliged to keep on with this epidemic faith when better days shall come.

Many disguised priests are now gliding and sliding here and there among the people, persuading them that a rosary which has been consecrated is a perfect preservative against the cholera.

The Saint-Simonists regard it as an advantage of their religion that none of their number can die of the prevailing malady, because progress is a law of nature, and as social progress is specially in Saint-Simonism, so long as the number of its apostles is incomplete none of its followers can die.

The Bonapartists declare that if any one feels in himself the symptoms of the cholera, if he will raise his eyes to the column of the Place Vendome he shall be saved and live.

And so hath every man his special faith in these troubled times.

As for me, I believe in flannel.

Good dieting can do no harm, but one should not eat too little, as do certain persons who mistake pangs of hunger felt in the night for premonitory symptoms of cholera. It is amusing to see the poltroonery which many manifest at table, regarding with defiance or suspicion the most philanthropic and benevolent dishes, and swallowing every dainty with a sigh.

The doctors told us to have no fear and avoid irritation; but they feared lest they might be unguardedly irritated, and then were irritated at themselves for being afraid. Now they are love itself, and often use the words Mon Dieu! and their voices are as soft and low as those of ladies lately brought to bed. Withal they smell like perambulating apothecary shops, often feel their stomachs, and ask every hour how many have died. But as no one ever knows the exact number, or either as there was a general suspicion as to the exactitude of the figures given, all minds were seized with vague terror, and the extent of the malady was magnified beyond limits.

In fact, the journals have since published that on one day, on the 10th of April, two thousand people died. But the people would not be deceived by any such official statement, and continually complained that far more died than were accounted for. My barber told me how an old woman sat at her window a whole night on the Faubourg Montmartre to count the corpses which were carried by, and she counted three hundred; but when morning came she was chilled with frost, and felt the cramp of the cholera, and soon died herself.

Wherever one looked in the streets, there he saw funerals, or, sadder still hearses with no one following. But as there were not hearses sufficient, all kinds of vehicles were used, which, when covered with black stuffs, looked very strange. Even these were at last wanting, and I saw coffins carried in hackney coaches. It was most disagreeable to see the great furniture wagons which were used for “moving” now moving about as dead men’s omnibuses, or omnibus mortuis, going from house to house for fares and carrying them by dozens to the field of rest.

The neighborhood of the cemetery where many funerals met presented the most dispiriting scene. Wishing to visit a friend one day, I arrived just as they were placing his corpse in the hearse. Then the sad fancy seized me to return the call which he had last made, so I took a coach and accompanied him to Pere la Chaise. Having arrived in the neighborhood of the cemetery, my coachman stopped, and awaking from my reverie, I could see nothing but literally sky and coffins.

I was among several hundred vehicles bearing the dead, which formed a queue or train before the narrow gate, and as I could not escape, I was obliged to pass several hours among these gloomy surroundings. Out of ennui, I asked my coachman the name of my neighbor corpse, and – what the chance! – he named a young lady whose coach had, some months before, as I was going to a ball at Lointier, been crowded against mine and delayed just as it was today. There was only this difference, that then she often put out of the window her little head, decked with flowers, her lovely, lively face lit by the moon, and manifested the most charming vexation and impatience at the delay.

Now she was quite still, and probably very blue; but ever and anon, when the mourning-horses of the hearses stamped and grew unruly, it seemed to me as if the dead themselves were growing impatient, and, tired of waiting, were in a hurry to get into their graves; and when, at the cemetery gate, one coachmen tried to get before another, and there was disorder in the queue, then the gendarmes came in with bare sabres; here and there were cries and curses, some vehicles were overturned, coffins rolling out burst open, and I seemed to see that most horrible of all emeutes — a riot of the dead.

To spare the feelings of my readers, I will not further describe what I saw at Pere la Chaise. Hardened as I am, I could not help yielding to the deepest horror. One may learn by deathbeds how to die, and then await death with calmness, but to learn how to be buried in graves of quicklime, among cholera corpses, is beyond my power.

I hastened to the highest hill of the cemetery, whence one may see the city spread out in all its beauty. The sun was setting; its last rays seemed to bid me a sad good-bye; twilight vapours cover sick Paris as with a light-white shroud, and I wept bitterly over the unhappy city, the city of freedom, of inspiration and of martyrdom, the saviour-city which has already suffered so much for the temporal deliverance of humanity.

Paris as seen from Pere-la-Chaise

Heinrich Heine: Cholera in Paris 2

Excerpt from The Works of Heinrich Heine, Vol. 14. Translated from the German by Charles Godfrey Leland.

It was amidst unparalleled trouble and confusion that hospital and other institutions for preserving public health were organized. A Sanitary Committee was created, Bureaux de Secours were established, and the ordinances as regards the salubrite publique were promptly put into effect. In doing this there was at once a collision with interests of several thousand men who regarded public filth as their own private property.

These were the chiffoniers or rag-men, who pick their living from the sweepings piled up in dirt heaps in odd corners. With great pointed baskets on their backs and hooked sticks in their hands, these men, with pale and dirty faces, stray through the streets, and know how to find and utilize many objects in these refuse piles. But when the police, not wishing this filth to remain longer in the public streets, had given out the cleaning to their agents, and the refuse, put into carts, was to be carried out into the open country, the chiffoniers could freely fish in it to their hearts’ content.

Then the latter complained that, though not reduced to starvation, that their business had been reduced, and that this industry was a right sanctioned by ancient usage, and like property, of which they could not be arbitrarily deprived. It is very curious that the proofs which they produced in this relation were quite identical with those which our country squires and nobles, chiefs of corporations, gild-masters, tithe-preachers, members of faculties, and similar possessors of privilege, bring forward when any old abuses by which they profit, or other rubbish of the Middle Ages, must be cleared away, so that our modern life may not be infected by the ancient musty mold and exhalations.

As their protests were of no avail, the chiffoniers attempted to oppose the reform of cleanliness by force, or got up a small counter-revolution, and that in connection with the old women called revendeuses, who had been forbidden to publicly sell on the quays or traffic in the evil-smelling stuff which they had bought from the chiffoniers.

Then we beheld the most repulsive riot; the new hand-cars used to clean the town were broken and thrown into the Seine; the chiffoniers barricaded themselves at the Porte Saint-Denis; the old women dealers in rubbish fought with their great umbrellas on the Chatelot; the general march was beaten; Casimir Perier had his myrmidons drummed up from their shops; the citizen-throne trembled; Rentes fell; the Carlists rejoiced.

The latter, by the way, had found at last their natural allies in rag-men and the old huxter-wives, who adopted the same principles as the champions of transmitted rights, or hereditary rubbish-interests and rotten things of every kind.

When the emeute of the chiffoniers was suppressed, and as the cholera did not take hold so savagely as was desired by certain people of the kind who in every suffering or excitement among the people hope, if not to profit themselves, to at least cause the overthrow of the existing Government, there rose all at one a rumour that many of those who had been so promptly buried had died not from disease but by poison. It was said that certain persons had found out how to introduce a poison into all kinds of foodt, be it in the vegetable markets, in bakeries, meat-stalls, or wine.

The more extraordinary these reports were, the more eagerly they were received by the multitude, and even the skeptics must needs believe in them when an order on the subject was published by the chief of police. For the police, who in every country seem to be less inclined to prevent crime than to appear to know all about it, either desired to display their universal information or else thought, as regards the tales of poisoning, that whether they were true or false, they themselves must in any case divert all suspicion from the Government.

Suffice it to say, that by their unfortunate proclamation, in which they distinctly said that they were on the track of the poisoners, they officially confirmed the rumours, and thereby threw all Paris into the most dreadful apprehension of death.

“We never heard the like!” said the oldest people, who, even in the most dreadful times of the Revolution, had never experienced such fearful crime. “Frenchmen! we are dishonoured!” cried the men, striking their foreheads. The women, pressing their little children in agony to the their hearts, wept bitterly and lamented that the innocent babes were dying in their arms. The poor people dared neither eat nor drink, and wrung their heads in dire need and distress. It seemed as if the end of the world had come.

The crowds assembled chiefly at the corners of the streets, where the red-painted wine-shops are situated, and it was generally there that men who seemed suspicious were searched, and woe to them when any doubtful objects were found on them. The mob threw themselves like wild beasts or lunatics on their victims. Many saved themselves by their presence of mind, others were rescued by the firmness of the Municipal Guard, who in those days patrolled everywhere; some received wounds or were maimed, while six men were unmercifully murdered outright.

Nothing is so horrible as the anger of a mob when it rages for blood and strangles its defenseless prey. Then there rolled through the streets a dark flood of human beings, in which, here and there, workmen in their shirtsleeves seemed like the white caps of a raging sea, and all were howling and roaring — all merciless, heathenish, devilish. I heard in the Rue Saint-Denies the well-known old cry. “A la lanterne!” and from voices trembling with rage I learned that they were hanging a prisoner. Some said that he was a Carlist, and that a brevet du lis had been found in his pocket; others declared he was a priest, and others that he was capable of anything.

In the Rue Vaugirard, where two men were killed because certain white powders were found on them, I saw one of the wretches, while he was still in the death rattle, and at the time old women plucked the wooden shoes from their feet and beat him on the head till he was dead. He was naked and beaten and bruised, so that his blood flowed…and one blackguard tied a rope to the feet of the corpse and dragged it through the streets, crying out, “Voila le chlera-morbus!”

A very beautiful woman, pale with rage, with bare breasts and bloody hands, was present, and as the corpse passed she kicked it. She laughed to me, and begged for a few francs reward for her dainty work wherewith to buy a mourning-dress, because her mother had died a few hours before of poison.

It appeared the next day by the newspapers that the wretched men who had been so cruelly murdered were all quite innocent, that the suspicious powders found on them consisted of camphor or chlorine; or some other kind of remedy against the cholera, and that those who were said to have been poisoned had died naturally of the prevailing epidemic. The mob here, like the same everywhere, being quick to rage and readily led to cruelty, became at once appeased , and deplored with touching sorrow its rash deeds when it heard the voice of reason.

With such voices the newspapers succeeded the next day in calming and quieting the populace, and it may be proclaimed, as a triumph of the press, that it was able so promptly to stop the mischief which the police had made.

I must here blame the conduct of certain people who by no means belonged to the lower class, yet who were so carried away by their prejudices as to publicly accuse the Carlista of poisoning. Passion should never carry us so far, and I should hesitate a long time ere I would accuse my most venomous foes of such horrible intentions. The Carlists were quite right in complaining of this, and it is only the bitter manner in which they cursed and raled over it which could excite suspicion.

That is certainly not the language of innocence. But according to the conviction of those best informed, there had been no poisoning. It may be that sham poisonings were contrived, or that a few wretches were really induced to sprinkle harmless powders on provisions in order to irritate and rouse the people; and if this was indeed the case, the people should not be too severely blamed for their riotous conduct, since it sprang not from public hate, “but in the interest of commonwealth, quite according to the theory of terrorism.”

Yes, the Carlists would themselves have perished in the pit dug for the Republicans, but the poisoning was not generally attributed to the one or to the other, but to that party which , “never conquered by arms, always raises itself again by cowardly means, which attains to prosperity and power invariably by the ruin of France, and which now, dispensing with the aid of Cossacks, may readily seek refuge in common poison.” This is about what is said in the Constitutional.

What I gained by personal observation on the day when these murders took place was the conviction that the rule of the elder branch of the Bourbons will never be reestablished in France. I heard the most remarkable utterances in different groups; I saw deep into the heart of the people — it knows its men.

To be continued…

Heinrich Heine: The Cholera in Paris

Excerpt from The Works of Heinrich Heine, Vol. 14. Translated from the German by Charles Godfrey Leland.

French Affairs: The Citizen Kingdom.

Paris, April 19, 1832

I will not borrow from the workshops of political parties their common vulgar rule wherewith to measure men and things; still less will I determine their greatness or value by dreamy private feelings. But I will contribute as much as possible impartially to the intelligence of the present, and seek the solution of the stormy, noisy enigma of the day in the past. Saloons lie, graves speak the truth. But ah! the dead, those cold reciters of history, speak in vain to the raging multitude, who only understand the language of passion.

Yet certainly the saloons do not lie with deliberate intention. The society of those in power really believes in its eternal duration, when the annals of universal history, the fiery Mene tekel of the daily journals, and even the loud voice of the people in the streets, cry aloud their warnings. Nor do the coteries of the Opposition utter predetermined falsehoods. They believe that they are sure to conquer, just as men always believe in what they most desire. They intoxicate themselves with the champagne of their hopes, interpret every mischance as a necessary occurrence which must bring them nearer to their goal. Their confidence flashes most brilliantly on the eve of their downfall.

And the messenger of justice who officially announced to them their defeat generally finds them quarreling as to their share in the bear’s skin. Hence the one-sided errors which we cannot escape when we stand too near to one or the other party; either deceives, yet does it unaware, and we confide most willingly in those who think as we do. But if we are by chance of such indifferent nature that we, without special predilection, keep in continual intercourse with all, then we are bewildered by the perfect self-confidence of either party, and our judgment is neutralized in the most depressing manner.

There are indeed such all-indifferent men who have no true opinions of the time, who only wish to learn what may be going on, to gather all the gossip of saloons, and retail all the chronique scandaleuse of one party to the other. The result of such indifference is that they see everywhere only persons and not principles, or rather that they see in principles only persons, and so prophesy the ruin of the first, because they have perceived the weakness of the latter, and thereby lead their constituents or those who believe in them into most serious errors and mistakes.

I cannot refrain from calling special attention to the false relationship which now exists in France between things (that is, spiritual and material interests) and persons (i.e., the representative of these). This was quite different at the end of the last century, when man towered so colossally to the height of things, so that they form in the history of the Revolution at the same time an heroic age, and as such are now celebrated, worshiped and loved by our Republican youth. Or are we in this respect deceived by the same error which we find in Madame Roland, who bewails so bitterly in her Memoirs that there was not among the men of her time one of importance?

The worthy lady did not know her own greatness, nor did she observe that her contemporaries were indeed great enough when they were in naught inferior to her as regards intellectual stature. The whole French people has today grown so mightily that we are perhaps unjust to its public representatives, who do not rise so markedly from the mob, yet who are not on that account to be considered as small. We cannot see the forest for the trees. In Germany we see the country, a terrible jungle of scraggy thicket and dwarf pines, and here and there a giant oak, whose head rises to the clouds – while down below the worms do gnaw its trunk.

Today is the result of yesterday. We must find out what the former would ere we can find what it is the latter will have. The Revolution is ever one and the same. It is not as the doctrinaires would have us think; it was not for the Charte that they fought in the great week, but for those same Revolutionary interests for which the best blood in France has been spilt for forty years. But that the author of these pages may not be mistaken merely for one these holders-forth who understand by revolution only one overthrow after another, and who see in accidental occurrences that which is the spirit of the Revolution itself, I will here explain the main idea as accurately as I can.

When the intellectual developments or culture of a race are no longer in accord with its old established institutions, there results necessarily a combat in which the latter are overthrown, and which is called a revolution. Until this revolution is complete, until that reformation of institutions does not perfectly agree with the intellectual development and the habits and wants of the people, just so long the national malady is not perfectly cured; and the sickly and excited people will often relapse into the weakness of their exhaustion.

Yet ever and anon be subject to attacks of burning fever, when they tear away the tightest bandages and the most soothing lint from the old wounds; throw the most benevolent, noblest nurses out of the window, and roll about in agony until they finally find them themselves in circumstances. That is, adapt themselves to institutions, which suit them better.

The question whether France is at rest, or whether we are to anticipate new political changes, and finally what end it will all take, amounts to this — What motive had the French in beginning a revolution, and have they obtained what they desired? To aid the reply I will discuss the beginning of the Revolution in my next article. This will be a doubly profitable occupation, since, while endeavoring to explain the present by the past, it will at the same time be shown how the past is made clear and in mutual understanding with the present, and how every day new light is thrown upon it, of which our writers of historical hand-books had no idea.